Anglo-Japanese style silverware

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880The Anglo-Japanese style refers to a period approximately 1872 to 1900 when a new awareness of, and appreciation for Japanese design and culture impacted architecture, and the decorative arts of the United Kingdom and United States.

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880The Anglo-Japanese style refers to a period approximately 1872 to 1900 when a new awareness of, and appreciation for Japanese design and culture impacted architecture, and the decorative arts of the United Kingdom and United States.

The style developed in parallel with the British Arts and Crafts Movement and the Aesthetic Movement. In furniture design the impact is seen in simple rectilinear lines, a simplification of pattern and motif, and a value placed on the handmade, using materials that ranged from expensive high style ebonized woods to humble materials like beech or printed paper. In ceramics the presence of the hand, use of reduction glazes as in the process, raku, organic form, and acceptance and celebration of imperfection. In commercial mass-produced ceramics the style was evoked more by motif: vignettes of bamboo, paper fans, and scenes of Japan.

The style anticipated the minimalism of twentieth century Modernism. British designers influenced by this style include Christopher Dresser, Edward William Godwin, James Lamb, William Morris, Philip Webb, and the decorative arts wall painting of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. In the United States some of the glass and silverwork by Louis Comfort Tiffany, textiles and wallpaper by Candace Wheeler, and the furniture of Nimura and Sato and the Herter Brothers (particularly that produced after 1870) shows influence of the Anglo-Japanese style.

Some of the most famous silversmiths in the Uniter States, especially Gorham and Tiffany, applied Japanese naturalistic designs on their products. For example, Gorham innovated a few design patterns like "Japanese", "Hizen" and "Narragansett" around 1880s. The designer of these patterns is not known however the strong relationship among these patterns suggests that some of unknown Japanese artists elaborated them. I think that a few of them had probably relationship with Saga or Nagasaki prefecture because the name of the pattern, "Hizen 肥前", means the former old province of Japan of which area is split into Saga 佐賀 and Nagasaki 長崎 prefectures today.

The Meiji government exhibited and sold the Japanese craft objects at the World's Fairs to promote domestic manufacturors. Starting with the Paris World's Fair in 1867, Japan participated in World's Fairs succesively, Vienna in 1873, Philadelphia in 1876, Paris in 1878, Paris in 1889, Chicago in 1893 and Paris in 1900. The response to the exhibitions and world fairs had a direct bearing on Japanese exports and foreign trade balance.

The products displayed at the 1867 Paris World's Fair were not manufactured specifically for the fair, instead craft objects used in daily life in Japan were selected and exhibited without particular consideration of their value as commercial exports. But from 1873 Vienna World's Fair, the craft products were specifically made for the fair, with eye to export value. In the category of metalwork, large, elaborately decorated, cast bronze vases, dishes, and incense burners (that would have no use in Japan but were popular as display objects in Victorian parlors) were exhibited, as well as small flower vases, dishes, incense burners with highly detailed engraving and colorful applied overlay patterns of birds and flowers that Westerners found exotic and attractive.

Bowl by Gorham, 1881Now we can clearly see that the designs applied on the Japanese craft objects exhibited in 1873 Vienna and 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair were directly reflected on US silverwares around 1880s. I am sure that it is possible to identify the Japanese artists brought the Japanese naturalism into US.

Bowl by Gorham, 1881Now we can clearly see that the designs applied on the Japanese craft objects exhibited in 1873 Vienna and 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair were directly reflected on US silverwares around 1880s. I am sure that it is possible to identify the Japanese artists brought the Japanese naturalism into US.

Seiji Yamauchi, 2009/11/29

Tête-à-tête Tea Service by Whiting, c. 1887

The Bowers/ Taft Family Aesthetic Movement Sterling Silver and Mixed-Metal Tête-à-tête Tea Service by Whiting, c. 1887

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880An outstanding example of American aesthetic movement silver in the Japanese taste, this rare tête-à-tête service is a great example of the exceptional work produced by Whiting of New York City. Based on the form of ancient traditional Japanese iron tea kettles, this service features textured surface decoration resembling woven bamboo, also a traditional Japanese design. Each piece is further decorated with fine applied decoration of peonies, bamboo and grape/ grape vines.

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880An outstanding example of American aesthetic movement silver in the Japanese taste, this rare tête-à-tête service is a great example of the exceptional work produced by Whiting of New York City. Based on the form of ancient traditional Japanese iron tea kettles, this service features textured surface decoration resembling woven bamboo, also a traditional Japanese design. Each piece is further decorated with fine applied decoration of peonies, bamboo and grape/ grape vines.

The quality of the design and decoration can clearly be seen in the handle of the tea pot, where the woven bamboo decoration is continued as faux (completely unnecessary) insulation when ivory insulators do the real insulating. Handles on the sugar bowl and cream jug resemble bound bamboo.

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880Tête-à-tête tea services are the rarest of the form. While most tea drinking was a social activity during the 18th, 19 and 20th centuries, the tête-à-tête service was meant for the very personal service of tea with only one other, with all the accompanying personal intimacies.

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880Tête-à-tête tea services are the rarest of the form. While most tea drinking was a social activity during the 18th, 19 and 20th centuries, the tête-à-tête service was meant for the very personal service of tea with only one other, with all the accompanying personal intimacies.

This beautiful tea service is marked underneath with Whiting’s trademark, ‘STERLING”, and the model number ‘462E’. It is monogrammed underneath ‘LBW’ for Louise Bennett Wilson. Together, the pieces weigh a fine 24.65 troy ounces and it is in very good/ excellent condition with light wear. One small section of the bamboo stalk on the sugar bowl has been well restored.

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880Provenance: Louise Bennett Wilson married Lloyd Bowers on 7 September 1887 -this was most likely a wedding present. Lloyd Bowers was an important lawyer and Yale schoolmate of President William Howard Taft who asked him to become Solicitor General of the United States upon his election in 1908. (He was a very successful Solicitor General, winning 13 of the 14 cases he argued before the Supreme Court.)

Japanese pattern fruit knives by Gorham, 1880Provenance: Louise Bennett Wilson married Lloyd Bowers on 7 September 1887 -this was most likely a wedding present. Lloyd Bowers was an important lawyer and Yale schoolmate of President William Howard Taft who asked him to become Solicitor General of the United States upon his election in 1908. (He was a very successful Solicitor General, winning 13 of the 14 cases he argued before the Supreme Court.)

Their only child, a daughter they named Martha Wheaton Bowers, was born on 17 December 1891. She inherited the service. Martha W. Bowers was educated at the Sorbonne in Paris and married Robert A. Taft, the eldest son of President Taft in 1914. Later, Robert A. Taft would become the famous U. S. Senator from Ohio.

Narragansett pattern of Gorham, circa 1884~

Narragansett pattern ladle by Gorham, 1884To the student of anthropology, this is the name of a tribe of Native Americans of the Algonquin family formerly living in Rhode Island, now almost extinct. To the student of geography, the term refers to Narragansett Bay, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean in southeastern Rhode Island named for the Indian tribe (Fig. 1). To the serious student of American silverware, Narragansett is a nineteenth-century flatware pattern made by the Gorham Manufacturing Company of Providence, Rhode Island, which took its name from the bay and its inspiration from the marine life that abounds there and elsewhere along the Atlantic coast.

Narragansett pattern ladle by Gorham, 1884To the student of anthropology, this is the name of a tribe of Native Americans of the Algonquin family formerly living in Rhode Island, now almost extinct. To the student of geography, the term refers to Narragansett Bay, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean in southeastern Rhode Island named for the Indian tribe (Fig. 1). To the serious student of American silverware, Narragansett is a nineteenth-century flatware pattern made by the Gorham Manufacturing Company of Providence, Rhode Island, which took its name from the bay and its inspiration from the marine life that abounds there and elsewhere along the Atlantic coast.

A tour de force of both design and craftsmanship, Narragansett is one of the most extraordinary flatware patterns ever created, but it is, nonetheless, not well known. It has rarely been published and is not mentioned in neither Charles Carpenter Jr.'s Gorham Silver or Noel Turner's American Silver Flatware, 1837-1910, both considered classics on the subject. (1) To those knowledgeable about Narragansett the pattern has acquired a mystique. The mere mention of the name evokes a frisson, and to the true flatware connoisseur touching a piece can be downright orgiastic.

Narragansett was a naturalistic pattern introduced in 1884. (2) Natural subjects such as shells, rocks, flowers, and foliage were prominent features of the rococo style, which developed in France in the eighteenth century, and of the rococo revival style, which appeared in England and the United States in the nineteenth. The use of natural forms evolved to the point of sometimes dictating the shape of objects as well as their decoration. Devoid of such frills as rococo C-and S-scrolls, this ultra-realistic style was fully developed in England by the 1840s and in the United States by the 1880s. Vegetal inspiration was most common, with sea life another favorite design source. When applied to flatware, the style led to spoon bowls modeled as flower blossoms, leaves, or shells, and handles that resembled twigs, bamboo, grapevines, or flowering branches. But no other naturalistic flatware as elaborate or as detailed as Narragansett was ever conceived.

All the pieces of Narragansett we have examined are constructed similarly. The handle consists of a cast stem to which multiple elements, mainly marine-related, are applied all around. The larger shell appliques, almost certainly cast from actual specimens, are highly naturalistic; the smaller ones, although possibly modeled from real life, are more stylized. Details as small as grains of sand are included. The functional ends are either cast or die-stamped and sometimes also have applied decoration.

All the pieces of Narragansett we have examined are constructed similarly. The handle consists of a cast stem to which multiple elements, mainly marine-related, are applied all around. The larger shell appliques, almost certainly cast from actual specimens, are highly naturalistic; the smaller ones, although possibly modeled from real life, are more stylized. Details as small as grains of sand are included. The functional ends are either cast or die-stamped and sometimes also have applied decoration.

It was formerly thought that only eleven types of pieces were ever made in the Narragansett pattern: ten serving pieces (fish knife and fork, salad fork and spoon, sugar spoon, jelly spoon, preserve spoon, berry spoon, gravy ladle, and soup ladle) and one place piece (an oyster fork). (3) However, on a recent visit to the Gorham Company archives at Brown University in Providence, we found evidence for two additional serving pieces: a punch ladle and a large sugar sifter. (4) The fish knife and fork, salad fork and spoon, and soup ladle were pictured (in reverse) in the autumn 1885 Gorham catalogue, (5) and there are labeled photographs of these same pieces and of the berry spoon (properly oriented) in the archives. To our knowledge the other pieces have never been illustrated; nor is there a surviving written description of any Narragansett piece.

Plates IIa and IIb show a Narragansett fish serving set. The terminal of the knife handle is formed as the thin shell of a steamer, or soft clam. The handle stem is decorated with cattails and various small shells; the shells that look like oblong open umbrellas appear to be marine gastropods known as keyhole limpets (family Fissurellidae). (6) There are also the spiral shells of various sea snails, including what look like beaded periwinkles (family Littorinidae), and spirally corded dove shells (family Columbellidae). A fish overlies the junction of the stem and blade, and the top margins of the blade are encrusted with seaweed, shells, and sand. (7) The upper blade is embossed with a shell-inspired design. A long, narrow blade of sea grass arises from the front of the stem bottom and coils around the handle, terminating on the reverse at the top of the stem.

The terminal of the fish serving fork is formed as a thick quahog clamshell, with a tiny sand crab applied to it. Multiple small shells and seaweed occupy the front and back of the stem. The functional end takes the form of a trident with an unusual pierced middle tine. The upper borders are encrusted with sand, and the bowl and tines have distress marks on their fronts, suggesting damage from a prolonged undersea stay There was a precedent for fake "damage" in the work of George W Shiebler (1846-1920) of New York City, (8) but the Narragansett pattern is the only one we are aware of in American flatware that includes "damage" supposedly due to underwater exposure.

The terminal of the fish serving fork is formed as a thick quahog clamshell, with a tiny sand crab applied to it. Multiple small shells and seaweed occupy the front and back of the stem. The functional end takes the form of a trident with an unusual pierced middle tine. The upper borders are encrusted with sand, and the bowl and tines have distress marks on their fronts, suggesting damage from a prolonged undersea stay There was a precedent for fake "damage" in the work of George W Shiebler (1846-1920) of New York City, (8) but the Narragansett pattern is the only one we are aware of in American flatware that includes "damage" supposedly due to underwater exposure.

The most striking feature of the fork is what is apparently an applied sea worm (see Pl. III), to judge by its smooth body, distinct mouth, and two eyes. (9) Its tail hooked on the middle tine, the creature coils across the bowl and then around the stem, its head located about one-third of the way up the handle. On another Narragansett fish fork, which with its matching knife sold at auction in 2002, (10) the sea worm is hooked on the right tine and curls around the back of the bowl and then around the stem. As unusual as these forks are, the concept of their decoration is not unique to Narragansett. In its earlier Hamburg flatware pattern (11) (almost as rare as Narragansett), Gorham executed a related design motif on a fish serving fork (Pl. IV). There, a longer and slightly fatter worm-like creature hooks its tail on the left tine and traverses the bowl to spiral twice around the stem. In addition to two eyes and a mouth, this animal has markings suggesting gills. (12)

Plates Ia and Ib illustrate the backs and fronts, respectively, of a Narragansett silver-gilt salad serving set. (13) As on the fish serving fork, the terminal of the fork is formed by a thick quahog clamshell with a tiny crab on it, and the stem is lavishly encrusted with marine elements. The three tines are twisted and have "underwater damage" marks on their fronts and backs. The terminal and stem of the salad serving spoon are similar but not identical to those of the fork. The bowl is formed as a large oyster shell with crenulated margins (Crassostrea virginica). A tiny shell, acorn barnacles, and sand lie within the well of the bowl. On the back of the bowl are sinuous tapering cylinders of about the same size and form as the worm on the fish serving fork, but they have the rough surface characteristics of twigs and lack identifiable features such as eyes or a mouth.

We are aware of two other Narragansett salad sets, both having the same shells forming the terminals and spoon bowls as the one just described but otherwise displaying a large number of small differences in applied decoration. (14) The variation among these three sets, as well as the different arrangement of the sea worm on the two fish forks, indicates that Gorham's artisans were given considerable license in the execution of each piece, which is not at all surprising in view of the pattern's complexity and aesthetic quality. Indeed, we would be surprised to ever see two identical pieces in this remarkable pattern.

We are aware of two other Narragansett salad sets, both having the same shells forming the terminals and spoon bowls as the one just described but otherwise displaying a large number of small differences in applied decoration. (14) The variation among these three sets, as well as the different arrangement of the sea worm on the two fish forks, indicates that Gorham's artisans were given considerable license in the execution of each piece, which is not at all surprising in view of the pattern's complexity and aesthetic quality. Indeed, we would be surprised to ever see two identical pieces in this remarkable pattern.

Plates Va and Vb picture a Narragansett berry spoon, (15) its gilt bowl modeled as a large oyster shell with scalloped margins. A twig twists along the right front margin of the bowl and a similar one extends down the back of the left side. The handle is decorated with some of the same marine elements as the previously described pieces. A berry spoon in the Dallas Museum of Art differs primarily in its different arrangement of shells down the stem. (16)

Until our recent visit to the Gorham Company archives we had believed the Narragansett soup ladle in Plates VIa and VIb was a Narragansett punch ladle, but an archival photograph identifies it as a soup ladle, and its weight (9 ounces troy, or 280 grams) is reasonably close to the average weight for a Narragansett soup ladle (9 ounces, 11 pennyweights troy or 297 grams) as opposed to that for a punch ladle (8 ounces, [unreadable single digit] pennyweights troy, or between 250 and 263 grams). (17) However, this same type of ladle is shown in another archival photograph alongside a twenty-four-pint bowl labeled as a punch bowl. (18) Presumably, Gorham felt that the overall size and proportions of the ladle were a better fit with this large punch bowl than were those of the designated but smaller punch ladle.

The terminal of the ladle is formed as an oyster shell (with a small applied crab) and the bowl as a large cockle shell. Two twisted plant stems arise at the base of the handle and spill over to the back of the bowl. The bowl is silver gilt, and various elements, including sand, seaweed, and fish, are gilded.

The terminal of the ladle is formed as an oyster shell (with a small applied crab) and the bowl as a large cockle shell. Two twisted plant stems arise at the base of the handle and spill over to the back of the bowl. The bowl is silver gilt, and various elements, including sand, seaweed, and fish, are gilded.

Plates VT[a and VIIb show what we presume to be the real Narragansett punch ladle. (19) Its weight (8 ounces, 3 pennyweights tray or 254 grams) approximates the average weight of Narragansett punch ladles. In length it is shorter than the soup ladle, an anomaly in late nineteenth-century silver. (20) The oyster-shell terminal is topped by a large applied crab (P1. Vila), and the decoration on the stem is similar to that on the other illustrated pieces except that a twig twines around the upper third. The gilt bowl is in the shape of a large bivalve shell. On the left side, a sinuous twig curves from the stem base around the back of the bowl. Another twig runs along the rim of the bowl on the right.

Plates VIIIa and VIIIb depict what we believe to be a Narragansett gravy ladle. Acquired more than a decade ago from an antiques dealer in Pennsylvania, it weighs 2 ounces, 16 pennyweights troy (87 grams), slightly more than the average for Narragansett gravy ladles (2 ounces, 10 pennyweights tray, or 78 grams). The bowl is modeled as a quahog clamshell with a gilt interior Tiny twigs parallel the top margins on each side, and seaweed flanks sand and barnacles at the top of the bowl on the back. The terminal is formed as a mussel shell. The stem is similar to others in the Narragansett pattern.

The spoon in Plate XIV, acquired through eBay, is tentatively identified as a preserve spoon. Gorham introduced the form in the Narragansett pattern in 1886. Typically a preserve spoon in a nineteenth-century flatware pattern was a smaller version of the berry spoon; in fact it was often given the double designation of small berry spoon/preserve spoon. (21) The example illustrated is indeed similar to the berry spoon (Pls. Va, Vb), only shorter (8 5/8 inches versus 10 1/16 inches) and lighter in weight (3 ounces, 7 pennyweights troy, or 104 grams, versus 4 ounces, 10 pennyweights tiny, or 139 grams). (22)

The spoon in Plate XIV, acquired through eBay, is tentatively identified as a preserve spoon. Gorham introduced the form in the Narragansett pattern in 1886. Typically a preserve spoon in a nineteenth-century flatware pattern was a smaller version of the berry spoon; in fact it was often given the double designation of small berry spoon/preserve spoon. (21) The example illustrated is indeed similar to the berry spoon (Pls. Va, Vb), only shorter (8 5/8 inches versus 10 1/16 inches) and lighter in weight (3 ounces, 7 pennyweights troy, or 104 grams, versus 4 ounces, 10 pennyweights tiny, or 139 grams). (22)

We have not been able to locate examples of the other specialized flatware forms known to have been made in the Narragansett pattern, namely the sugar spoon, jelly spoon, sugar sifter; and oyster fork. We hope readers will contact us if they have pieces that might fit these roles. (23)

We have, however, found a number of objects that might have been a part of the Narragansett line, even though there are no records documenting that the forms were made in the pattern. Plate IX illustrates an example--a combination olive spoon-fork. (24) In an archival photograph it is identified only as "olive spoon and fork no. 273," and it is not included among costing ledger entries for Narragansett. The stem is cast as a slender tree branch, one end forking into two tines; the spoon end is applied, shaped as a mussel shell with a gilt interior. Except for less lavish embellishment and fewer fine details (no sand, for example), this piece is quite similar in style to the confirmed Narragansett pieces already illustrated and described. A similar olive spoon-fork with slightly different applied decoration was sold at auction several years ago, (25) and we are aware of at least one other similar implement in a private collection.

Illustrated in Plates Xa and Xb is a napkin ring, which is not of course, strictly speaking, a piece of flatware. (26) Supported on four feet modeled as shells (mussel, scallop, oyster, and clam), it has irregularly crenate ends that are encrusted with sand and various types of aquatic life, and other marine-related elements adorn the lower sides. The decoration is clearly related to the Narragansett pattern, but there is no evidence that Gorham considered it part of the pattern. It is identified in an archival photograph only by its number; "1750."

Illustrated in Plates Xa and Xb is a napkin ring, which is not of course, strictly speaking, a piece of flatware. (26) Supported on four feet modeled as shells (mussel, scallop, oyster, and clam), it has irregularly crenate ends that are encrusted with sand and various types of aquatic life, and other marine-related elements adorn the lower sides. The decoration is clearly related to the Narragansett pattern, but there is no evidence that Gorham considered it part of the pattern. It is identified in an archival photograph only by its number; "1750."

The rare brooch in Plate XII is another non-flatware item in the Narragansett style. The core is a knobby branch on which are applied various decorative marine elements. The markings include a pattern number; "600," but a search of the Gorham Company archives turned up no records relating to a piece of jewelry with this number.

The ten oyster forks in Plate XIII are stylistically similar to Narragansett flatware and are often confused with it, but they are from a pattern called Bluepoint, consisting of twelve oyster forks, each with a different design, introduced in 1884. (27) They are identified by this name in an archival photograph and in an illustration in Gorham's autumn 1884 catalogue. (28) Gorham's records document substantially lower average weights and cheaper wholesale prices for Bluepoint oyster forks than for those of Narragansett oyster forks--$27 per dozen for Bluepoint versus $48 for Narragansett. The stems, modeled as bamboo, one end dividing into three tines, are variously applied with bamboo leaves and other leaves and with various marine elements. Each is encrusted with barnacles (29)

Plate XI illustrates four teaspoons also in the Narragansett style. They are pan of a set of twelve, each of a different design, identified in an archival photograph and in Gorham catalogue illustrations as simply "Five O'Clock Spoons." (30) Also introduced in 1884, they have stems formed as twigs entwined with sea grass and/or seaweed, and each is applied with a small shell or other aquatic motif. Each bowl is different.

The manufacture of Narragansett was difficult and expensive. Gorham records indicate that the "making cost," that is, the cost directly attributable to the work of the silversmith, and the "net cost" (the total cost including overhead and profit) were about one and one-half to two times more for Narragansett than those of comparable pieces in most other Gorham patterns of the era. A Gorham price book of 1887 shows wholesale prices of $17 for the fish knife, $14 for the fish fork, $17.50 each for the salad fork and spoon, $15 for the berry spoon, $29 for the soup ladie, $27 for the punch ladle, and $9.25 for the gravy ladle. (31) These were hefty sums for flatware in the late nineteenth century Estimated retail prices in 2001 dollars for the above pieces would be $530, $435, $549, $473, $908, $852, and $284, respectively. (32) The extreme rarity of Narragansett today suggests the pattern was sold in very limited quantities, and cost must surely have played a significant role, although it is also likely that th is pattern was simply too exotic for the taste of some silver buyers.

The manufacture of Narragansett was difficult and expensive. Gorham records indicate that the "making cost," that is, the cost directly attributable to the work of the silversmith, and the "net cost" (the total cost including overhead and profit) were about one and one-half to two times more for Narragansett than those of comparable pieces in most other Gorham patterns of the era. A Gorham price book of 1887 shows wholesale prices of $17 for the fish knife, $14 for the fish fork, $17.50 each for the salad fork and spoon, $15 for the berry spoon, $29 for the soup ladie, $27 for the punch ladle, and $9.25 for the gravy ladle. (31) These were hefty sums for flatware in the late nineteenth century Estimated retail prices in 2001 dollars for the above pieces would be $530, $435, $549, $473, $908, $852, and $284, respectively. (32) The extreme rarity of Narragansett today suggests the pattern was sold in very limited quantities, and cost must surely have played a significant role, although it is also likely that th is pattern was simply too exotic for the taste of some silver buyers.

The designer of Narragansett is not known. George Wilkinson (1819- 1894), the eminent British-born designer who, except for a brief interlude in 1860, worked for Gorham from 1857 until his death, became general superintendent of the manufactory in 1870 and may not have continued as a designer thereafter. (33) In any case, Narragansett is unlike anything Wilkinson is known to have designed. The famous French designer Florent Antoine Heller (1839- 1904), who was actually enticed to come to the United States by Tiffany and Company of New York City in 1873, worked for Gorham for a few years before switching to Tiffany. (34) Shortly after returning to France in 1880, he was lured back to work again for Gorham and designed Gorham's important flatware patterns in the beaux arts tradition: Fontainebleau (1882), Medici and Cluny (both 1883), Nuremburg (1884), and others subsequently. (35) However, he is not known to have created anything in the naturalistic mode. William Christmas Codman (1839-1921), the great English designer who was responsible for no fewer than fifty-five flatware patterns for Gorham, did not join the firm until 1891. (36)

Art historians and curators were long reluctant to consider utilitarian silver such as flatware an art form, but American an silver of the second half of the nineteenth century has now found a secure place in many important museum collections, and even the most closed-minded observer would be hard pressed not to find aesthetic merit in the Narragansett pieces.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Samuel J. Hough, the librarian who originally organized and prepared a five-hundred page inventory of the Gorham Company archives; and Mark Brown, curator of manuscripts, John Bay Library, Brown University Providence, Rhode Island.

(1.) Charles H. Carpenter Jr., Gorham Silver, rev. ed. (Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, San Francisco, 1997); Noel D. Turner, American Silver Flatware, 1837-1910 (A. S. Barnes, San Diego, 1972; reprinted Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, San Francisco, 1998).

(2.) Narragansett was first entered in the company's costing ledger in June 1884. The ledger and all other Gorham records cited in this article are now in the Gorham Company archives, special collections, John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

(3.) Charles L. venable, Silver in America, 1840-1940: A Century of Splendor (Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, 1994), p. 345 (checklist for Fig. 6.60). These were the eleven items entered in Gorham's cost books between 1884 and 1886.

(4.) These two pieces are listed in "Price book, New York, 1887," p.49 (Gorham Company archives).

(5.) A copy of the catalogue is in the Gorham Company archives.

(6.) For the identification of these and other exotic shells mentioned in this article, we are indebted to M.G. Harasewych, curator of marine mollusca in the department of systematic biology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. According to Harasewych, the keyhole limpets on this piece occur most commonly in Florida and the Caribbean, although one species extends as far north as Maryland or Delaware; these are only distantly related to the true limpets present along the New England coast.

(7.) The flatware terminology scheme used here is that outlined in William P. Hood Jr., with Roslyn Berlin and Edward Wawrynek, Tiffany Silver Flatware, 1845-1905: When Dining Was an Art (Antique Collectors' Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, [2000]), Appendix A, pp. 305-306. "Upper" refers to toward the handle terminal, the "top." "Lower" refers to toward the functional end, the "bottom."

(8.) The Homeric flatware pattern designed and made by Shiebler c. 1880 included "damage" to evoke its imaginary origin in antiquity.

(9.) Given the few recognizable characteristics of this creature, it is hazardous to make a specific identification. Nevertheless, given the marine setting, the animal probably represents a ribbon worm (phylum Nemertea) modeled incorrectly Precise identity is hindered by apparent anatomical inaccuracies in the modeling. This creature's mouth is horizontal, whereas that of a ribbon worm is a simple round or elongate opening at or below its front end. And there should be several eyes, not just two (M. G. Harasewych, e-mail to William P. Hood Jr., May 9, 2001).

(10.) Important Americana, sale no. 7756, Sotheby's, New York, January 18, 2002, Lot 500.

(11.) This pattern was first entered in Gorham's costing records in 1883.

(12.) As with the previous worm, precise identification is difficult. As before, this creature has a horizontal mouth and two eyes, plus the markings suggesting gills. These features would be compatible with an eel, but the animal's narrowness in relation to its relatively long length goes against this. So, it might represent a ribbon worm or an eel, modeled incorrectly in either case (Harasewych e-mail to Hood, May 9, 2001).

(13.) This salad serving set was at one time in the Jerome Rapoport collection, having been acquired by him at auction (Fine American Furniture, Silver, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, sale no. 7146, Christie's, New York, October 19, 1990, Lot 29). it was purchased by its present owner at the Rapoport sale (The Jerome Rapoport Collection of American Aesthetic Silver, sale no. 6873, Sotheby's, New York, June 20, 1996, Lot 63).

(14.) One of these sets is in a private collection. The other, the present whereabouts of which is unknown, was included in Important American Furniture, Silver, Prints, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, sale no. 7398, Christie's, New York, January 17, 1992, Lot 56.

(15.) An alert collector spotted this specimen at a flea market in Atlanta in 1992.

(16.) This piece is pictured in Venable, Silver in America, 1840-1940, p. 189, Fig. 6.60. A third Narragansett berry spoon is in a private collection, but no details about it are available.

(17.) This and subsequently recorded average weights are found in Gorham's archives and included here with permission of the Brown University Library. Some variation in weight is inevitable due to the variable number and size of appliques and the variable quantity of silver solder used.

(18.) Carpenter (Gorham) Silver, p.82, Fig. 93) also pictures a ladle very similar in size and decoration to the one in Pls. VIa and VIb with a large punch bowl. Both pieces are in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

(19.) This piece was included in The Winter Catalogued Auction, Freeman/Fine Arts, Philadelphia, December 6, 1990, Lot 85. In the sale catalogue, it was called an "ornate bouillabaisse ladle"; it was not identified as being part of the Narragansett pattern.

(20.) Between about 1850 and 1875 the opposite was usually the case, probably reflecting the fact that at that time punch was usually served in more intimate--and exclusively male-groups than in the 1880s and 1890s.

(21.) Richard Osterberg, Yesterday's Silver for Today's Table: A Silver collector's Guide to Elegant Dining (Schiffer; Atglen, Pennsylvania, 2001), p. 79.

(22.) The weight of this piece approximates the average weight of a Narragansett preserve spoon (3 oz. tiny, or 93 grams).

(23.) Please e-mail Bhood2000@aol.com

(24.) This piece was purchased at Important American Furniture Silver, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, sale no. 8208, Christie's, New York, June 21, 1995, Lot 55.

(25.) Important American Furniture, Silver, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, sale no. 8418, Christie's, New York, June 19, 1996, Lot 34. The present whereabouts of this piece is unknown.

(26.) The napkin ring was included in Highly Important American Furniture, Silver and Folk Art, sale no. 7000, Christie's, New York, January 19, 1990, Lot 74.

(27.) This pattern was entered in the Gorham costing ledger in August 1884.

(28.) A copy of the catalogue is in the Gorham Company archives.

(29.) Ten examples of Bluepoint, including many identical to those illustrated in Pl. XIII, were included in Important Nineteenth Century American Silver: Property of Masco Corporation, sale no. 7088, Sotheby's, New York, January 20,1998, part of Lot 54.

(30.) Such spoons are illustrated in Gorham's autumn 1887 catalogue (Gorham Company archives). Examples of the same four types of "Five O'Clock Spoons" as those pictured here were sold at important Nineteenth Century American Silver: Property of Masco Corporation, part of Lot 54.

(31.) These prices, as well as those for the Bluepoint and Narragansett oyster forks are from the price book cited in n. 4, and are quoted with permission of Brown University Library.

(32.) The nineteenth-century prices are from ibid. Nineteenth-century retail prices were estimated on the basis that the wholesale price usually represented 60 percent of the retail price (telephone conversation with Samuel Hough, February 8, 2002). The equivalent 2001 retail dollar values were derived with S. Morgan Friedman's "Inflation Calculator" (www.westegg.com/inflation), using 1887 as the base year.

(33.) Venable, Silver in America, 1840-1940, p.49.

(34.) Ibid., p. 78. At Tiffany's he contributed to the design of Olympian and possibly other patterns.

(35.) Carpenter, Gorham Silver, pp. 93-103.

(36.) Venable, Silver in America, 1840-1 940, pp. 155-156.

Magazine Antiques Sept, 2002 by William P. Hood, Jr., John R. Olson, Charles S. Curb, Willis H. Thompson, III

Anglo-Japanese Style Glassware

François-Eugène Rousseau (1827-1890)

Japonisme Vase, circa 1878. Japanese art inspired the bag-like shape and fish and waterweed decoration of this vase. This vase was shown in the International Exhibition, Paris, in 1878. Victoria & Albert MuseumIn 1855 François-Eugène Rousseau, inherited the family retail ceramics and glass shop at 41 rue Conquilere in Paris, succeeding both his father and his grandfather.

Japonisme Vase, circa 1878. Japanese art inspired the bag-like shape and fish and waterweed decoration of this vase. This vase was shown in the International Exhibition, Paris, in 1878. Victoria & Albert MuseumIn 1855 François-Eugène Rousseau, inherited the family retail ceramics and glass shop at 41 rue Conquilere in Paris, succeeding both his father and his grandfather.

In 1867 he commissioned a dinner service from the painter and etcher Felix Brancquemond. It consisted of over 200 different designs of fish, crustanceans and animals in a Japanese style derived from Hokusai. It was immediately popular and sold in his shop for several years. Encouraged by this success, he determined to experiment with glass.

He hired two of the greatest glass designers, makers and engravers of their era, Eugene Michel in 1867 and Alphonse-Georges Reyem in 1877. In 1877 Ernest-Baptiste Leveille (1841-1913) joined as a decorator. Rousseau continued to work with Appert Freres.

Eugene Michel engraved table glass and crystal vases and bowis with Japanese ornaments and floral patterns, while Rousseau himself spent more and more time at the glassworks of Appert Freres. Founded at Clichy in 1835 by Louis Appert, it was then run by his two sons. Adrien and Leon, who turned it into one of the most successful glassworks of the period in France. Leon was of the most eminent glass technicians of his day, and wrote several technical books on the subject with Jules Nenrivaux. Appert Freres produced a wide variety of glass for every purpose, from stained glass windows to wall cladding, optical glass, laboratory glass, reinforced glass and some art glass. Although brothers to experiment ceaselessly to produce new and vibrant colours. Victor Champier wrote in 1891 in the Revue Arts Decoratifs, "They invented for him a hole palette running from blood red to pale violet, and made for him vases that looked like precious stones: the richness and hardness of agate, opaline softness, mother of pearl reflections, onyx iridescence."

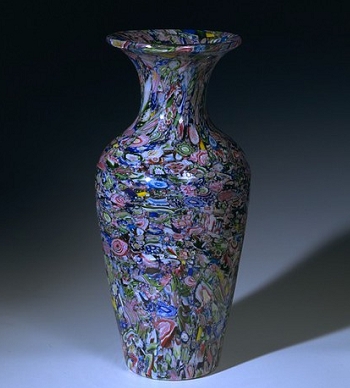

Millefiori glass by Appert Frères, circa 1850. H: 28.5cm. Victoria & Albert Museum.All Rousseau's early vessels were executed by Appert Freres and, even when he opened his own glass-making studio, he continued to sonsult them on technical matters, as indeed did many other glass designers and makers, including Emile Galle and Daum Freres.

Millefiori glass by Appert Frères, circa 1850. H: 28.5cm. Victoria & Albert Museum.All Rousseau's early vessels were executed by Appert Freres and, even when he opened his own glass-making studio, he continued to sonsult them on technical matters, as indeed did many other glass designers and makers, including Emile Galle and Daum Freres.

Rousseau designed and made a wide variety of vessels, some in carefully composed shapes, others in extraordinary free forms that alternated thin with thich-walled glass, tranparent pastel colours with opaque ones, applying sections to the outside from detailed insects to elephant-head handles, perfecting the technique of internal cracklingby plunging the hot parison from the kiln into a bucket of cold water. Another glass style which he developed was to case a crackle glass with clear glass, and in so doing capture metallic oxides and gold leaf between the two layers. Intaglio would sometimes be added and also metal mounts and fittings.

As his mastery of the medium increased, he combined several techniques in a single vessel. The full range of his creations was shown at the 1884 Paris Exhibition organized by the Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs, which later established Hors Concours (a great honour, placing him above those whose entries were eligible for prizes). He was awarded the Legion d'Honneur later that year.

He also worked at Sevres alongside Marc Louis Solon. (Solon was to go on to produce pate sur pate at Minton's in the UK).

Rousseau was respected among the professional art glass workers of his day, although he enjoyed only limited commercial success.

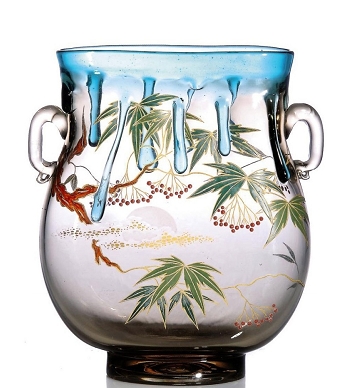

Japonisme Vase, circa 1885. Decorated with Japanese scene with moon and trees, with applied trails and applied handles. H: 22cm. Sold at GBP 3,750 in Oct 2010, Christie's.In 1885 he sold his workshop to his former pupil and assistant Ernest-Baptiste Leveille. Leveille continued to produce Rousseau designs for some time. Most of Rousseau's vases were unsigned, but some that were in stock were signed at Leveille's instigation.

Japonisme Vase, circa 1885. Decorated with Japanese scene with moon and trees, with applied trails and applied handles. H: 22cm. Sold at GBP 3,750 in Oct 2010, Christie's.In 1885 he sold his workshop to his former pupil and assistant Ernest-Baptiste Leveille. Leveille continued to produce Rousseau designs for some time. Most of Rousseau's vases were unsigned, but some that were in stock were signed at Leveille's instigation.

Rousseau stayed on until 1888 when his health forced him to retire.

Rousseau died in 1891.

Leveille changed the name of the business to Rousseau & Leveille Reunis and moved the premises to 74 Boulevard Haussmann. He continued to use Rousseau's techniques in his own vessels although his shapes were often more tormented and occasionally of Art Nouveau inspiration.

Shortly after 1900 Leveille merged with Maison Toy which had a prestigious address at 10 rue de la Paix. He produced some fine tableware marked Toy & Leveille, but the beginning of the 20th century was financially difficult and he was forced to sell the business to Haraud and Guignard, the owner ofLe Rosey. Haraud-Guignard continued to produce exxisting Leveille designs for some years signing them with either the initials HG or Le Rosey. Leveille himself died totally forgotten in 1913.

Whether produced by Rousseau or by Leveille these vases are extremely rare and considered one of the creative summits of glass production in the late 19th century in France. Rousseau is very interesting as it pre-emptied the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements some items have a strong naturalistic theme.

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me