Art Nouveau

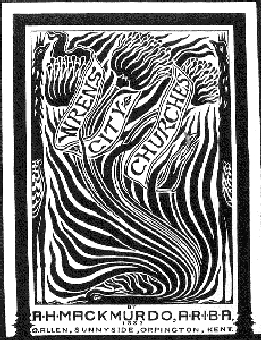

The book-cover by Arthur Mackmurdo for Wren's City Churches (1883) is often cited as the first realization of Art NouveauThe first realization of Art Nouveau is often considered to be Arthur Mackmurdo's book-cover for Wren's City Churches (1883), with its rhythmic floral patterns.

The book-cover by Arthur Mackmurdo for Wren's City Churches (1883) is often cited as the first realization of Art NouveauThe first realization of Art Nouveau is often considered to be Arthur Mackmurdo's book-cover for Wren's City Churches (1883), with its rhythmic floral patterns.

Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo(1851–1942) was a progressive English architect and designer, who influenced the Arts and Crafts Movement, notably through the Century Guild of Artists, which he set up in partnership with Selwyn Imagein 1882. He was educated at Felsted School. Mackmurdo started his apprenticeship with Gothic Revival architect James Brooks in 1869. In 1873, he visited John Ruskin's School of Drawing, and accompagnied Ruskin to Italy in 1874. That same year, Mackmurdo opened his own architectural practice at 28, Southampton Street, in London.

The Century Guild of Artists was one of the more successful craft guilds set up in the 1880s. It offered complete furnishing of homes and buildings, and its artists were encouraged to participate in production as well as design; Mackmurdo himself mastered several crafts, including metalworking and cabinet making.

Although Art Nouveau took on distinctly localized tendencies as its geographic spread increased—discussed below—some general characteristics are indicative of the form. A description published in Pan magazine of Hermann Obrist's wall-hanging Cyclamen (1894) described it as "sudden violent curves generated by the crack of a whip,", which became well-known during the early spread of Art Nouveau.

Subsequently, not only did the work itself become better-known as the Whiplash, but the term "Whiplash" is frequently applied to the characteristic curves employed by Art Nouveau artists. Interestingly the whiplash pattern spoon made by Paul de Lamerie in mid 1730s, at the start of English Rococo period, was one of origins of the naturalistic spoon. Such decorative "whiplash" motifs, formed by dynamic, undulating, and flowing lines in a syncopated rhythm, are found throughout the architecture, painting, sculpture, and other forms of Art Nouveau design.

Alexandre Charpentier (1856-1909), Dining room set of the banker Adrien Bénard in Champrosay, 1901. Mahogany, oak and poplar; metalwork of gilt bronze; Flower stand of enamelled stoneware. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, © Photo RMN, Hervé LewandowskiArt Nouveau is now considered a 'total' style, meaning that it encompasses a hierarchy of scales in design — architecture; interior design; decorative arts including jewelry, furniture, textiles, household silver and other utensils, and lighting; and the range of visual arts. Art Nouveau was a movement that was very broad in its scope. To many Europeans, it encompassed a whole way of life. It was possible to live in an art nouveau-inspired house with art nouveau furniture, silverware, crockery, jewellery, cigarette cases, etc. The Art Nouveau movement wanted to make art part of everyday life, thought to break all connections to classical times, and bring down the barriers between the fine arts and applied arts. Art Nouveau was underlined by a particular way of thinking about modern society and new production methods, attempting to redefine the meaning and nature of the work of art, so that art would not overlook any everyday object, no matter how utilitarian. Hence the name Art Nouveau - "New Art". This total style concept could be observed in Emile Galle's works - glass, ceramics, furniture.

Alexandre Charpentier (1856-1909), Dining room set of the banker Adrien Bénard in Champrosay, 1901. Mahogany, oak and poplar; metalwork of gilt bronze; Flower stand of enamelled stoneware. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, © Photo RMN, Hervé LewandowskiArt Nouveau is now considered a 'total' style, meaning that it encompasses a hierarchy of scales in design — architecture; interior design; decorative arts including jewelry, furniture, textiles, household silver and other utensils, and lighting; and the range of visual arts. Art Nouveau was a movement that was very broad in its scope. To many Europeans, it encompassed a whole way of life. It was possible to live in an art nouveau-inspired house with art nouveau furniture, silverware, crockery, jewellery, cigarette cases, etc. The Art Nouveau movement wanted to make art part of everyday life, thought to break all connections to classical times, and bring down the barriers between the fine arts and applied arts. Art Nouveau was underlined by a particular way of thinking about modern society and new production methods, attempting to redefine the meaning and nature of the work of art, so that art would not overlook any everyday object, no matter how utilitarian. Hence the name Art Nouveau - "New Art". This total style concept could be observed in Emile Galle's works - glass, ceramics, furniture.

A high point in the evolution of Art Nouveau was the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, which presented an overview of the 'modern style' in every medium. It achieved further recognition at the Esposizione Internazionale d'Arte Decorativa Moderna of 1902 in Turin, Italy, where designers exhibited from almost every European country where Art Nouveau was practiced.

Tea & Coffe set, WMF Comapny, circa 1900. Detais of thia teaset are published in the book: "Art Nouveau Demestic Metalwork from Wurttembergische Metallwarenfabrik", The English Cataloggue 1906, on page 187, 192, 215. As an art movement it has affinities with the Pre-Raphaelitesand the Symbolism movement, and artists like Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Edward Burne-Jones, Gustav Klimt, and Jan Toorop could be classed in more than one of these styles. Unlike Symbolist painting, however, Art Nouveau has a distinctive visual look; and, unlike the artisan-oriented Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau artists quickly used new materials, machined surfaces, and abstraction in the service of pure design. Art Nouveau did not negate the machine as the Arts and Crafts Movement did, but used it to its advantage. For sculpture, the principle materials employed were glass and wrought iron, leading to sculptural qualities even in architecture. It made use of many technological innovations of the late 19th century, especially the broad use of exposed iron and large, irregularly shaped pieces of glass in architecture.

Tea & Coffe set, WMF Comapny, circa 1900. Detais of thia teaset are published in the book: "Art Nouveau Demestic Metalwork from Wurttembergische Metallwarenfabrik", The English Cataloggue 1906, on page 187, 192, 215. As an art movement it has affinities with the Pre-Raphaelitesand the Symbolism movement, and artists like Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Edward Burne-Jones, Gustav Klimt, and Jan Toorop could be classed in more than one of these styles. Unlike Symbolist painting, however, Art Nouveau has a distinctive visual look; and, unlike the artisan-oriented Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau artists quickly used new materials, machined surfaces, and abstraction in the service of pure design. Art Nouveau did not negate the machine as the Arts and Crafts Movement did, but used it to its advantage. For sculpture, the principle materials employed were glass and wrought iron, leading to sculptural qualities even in architecture. It made use of many technological innovations of the late 19th century, especially the broad use of exposed iron and large, irregularly shaped pieces of glass in architecture.

By the start of the First World War, however, the highly stylised nature of Art Nouveau design—which itself was expensive to produce—began to be dropped in favour of more streamlined, rectilinear modernism that was cheaper and thought to be more faithful to the rough, plain, industrial aesthetic that became Art Deco.

Art & Craft Movement

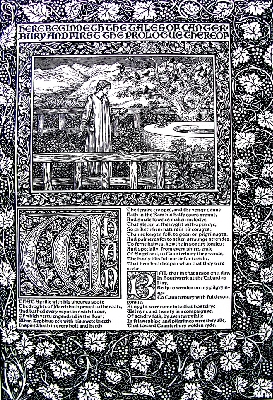

The Kelmscott Press edition of The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, with decorations by Morris and illustrations by Burne-Jones, is sometimes counted among the most beautiful books ever produced.The origins of Art Nouveau are found in the resistance of William Morris (1834-1896) to the cluttered compositions and the revival tendencies of the Victorian era. Inspired by the writings of John Ruskin and a romantic idealization of a craftsperson taking pride in their personal handiwork, it was at its height between approximately 1880 and 1910.

The Kelmscott Press edition of The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, with decorations by Morris and illustrations by Burne-Jones, is sometimes counted among the most beautiful books ever produced.The origins of Art Nouveau are found in the resistance of William Morris (1834-1896) to the cluttered compositions and the revival tendencies of the Victorian era. Inspired by the writings of John Ruskin and a romantic idealization of a craftsperson taking pride in their personal handiwork, it was at its height between approximately 1880 and 1910.

The Arts and Crafts Movement began primarily as a search for authentic and meaningful styles for the 19th century and as a reaction to the eclectic revival of historic styles of the Victorian era and to "soulless" machine-made production aided by the Industrial Revolution. Considering the machine to be the root cause of all repetitive and mundane evils, some of the protagonists of this movement turned entirely away from the use of machines and towards handcraft, which tended to concentrate their productions in the hands of sensitive but well-heeled patrons.

William Morris was an English architect, furniture and textile designer, artist, writer, socialist and Marxist associated with the Pre-Raphaelites and the English Arts and Crafts Movement. Born in Walthamstow in East London, Morris was educated at Marlborough and Exeter College, Oxford. In 1856, he became an apprentice to Gothic revival architect George Edmund Street. That same year he founded the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, an outlet for his poetry and a forum for development of his theories of hand-craftsmanship in the decorative arts. In 1861, Morris founded a design firm in partnership with the artist Edward Burne-Jones, and the poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti which had a profound impact on the decoration of churches and houses into the early 20th century. His chief contribution to the arts was as a designer of repeating patterns for wallpapers and textiles, many based on a close observation of nature. He was also a major contributor to the resurgence of traditional textile arts and methods of production.

William Morriss formed the Kelmscott Press and also had a shop where he designed and sold products such as wallpaper, textiles, furniture, etc. Morris's own ideas emerged from the thinking that had informed Pre-Raphaelitism, especially following the publication of Ruskin's book The Stones of Venice and Unto this Last, both of which sought to relate the moral and social health of a nation to the qualities of its architecture and designs.

Textile design by William Morris "Strawberry Thief", chintz, 1883The decline of rural handicrafts, corresponding to the rise of industrialised society, was a cause for concern for many designers and social reformers, who feared the loss of traditional skills and creativity. For Ruskin, a healthy society depended on skilled and creative workers. Morris and other socialist designers such as Walter Crane and Charles Robert Ashbee looked forward to a future society of free craftspeople. The aesthetic movement, which emerged at the same period, fed into these ideas. In 1881 the Home Arts and Industries Association was set up by Eglantyne Louisa Jebb in collaboration with Mary Fraser Tytler (later Mary Watts) and others to promote and protect rural handicrafts. A group of reformist architects, followers of Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, later established the Art Workers Guild to promote their vision of the integration of designing and making, lead by its first master George Blackall Simonds. This was followed by the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, formed in 1887 with Walter Crane as president. The Society held the first of a series of Exhibitions in London's New Gallery in November 1888. This was the first gallery show of contemporary decorative arts in London since cartoons for mosaic, tapestry, and glass were included in the Grosvenor Gallery's Winter Exhibition of 1881.

Textile design by William Morris "Strawberry Thief", chintz, 1883The decline of rural handicrafts, corresponding to the rise of industrialised society, was a cause for concern for many designers and social reformers, who feared the loss of traditional skills and creativity. For Ruskin, a healthy society depended on skilled and creative workers. Morris and other socialist designers such as Walter Crane and Charles Robert Ashbee looked forward to a future society of free craftspeople. The aesthetic movement, which emerged at the same period, fed into these ideas. In 1881 the Home Arts and Industries Association was set up by Eglantyne Louisa Jebb in collaboration with Mary Fraser Tytler (later Mary Watts) and others to promote and protect rural handicrafts. A group of reformist architects, followers of Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, later established the Art Workers Guild to promote their vision of the integration of designing and making, lead by its first master George Blackall Simonds. This was followed by the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, formed in 1887 with Walter Crane as president. The Society held the first of a series of Exhibitions in London's New Gallery in November 1888. This was the first gallery show of contemporary decorative arts in London since cartoons for mosaic, tapestry, and glass were included in the Grosvenor Gallery's Winter Exhibition of 1881.

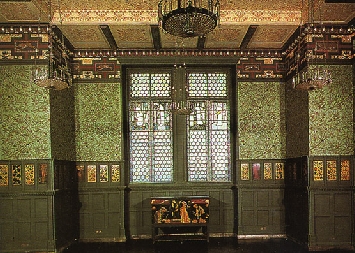

William Morris, green dining room interior, commissioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

William Morris, green dining room interior, commissioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me