Japanese Laquerware "Maki-e" Collection and Rococo Naturalism

History

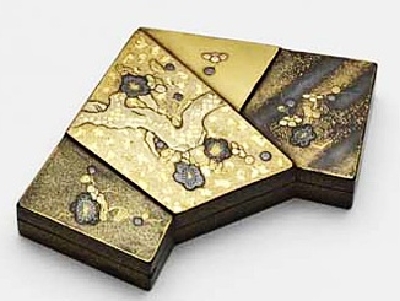

Folded Letter-shaped Incense Container, Edo period, late 17th century to mid 18th century. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France.Makie (literally, "sprinkled picture") is a distinctive Japanese decorative technique in which designs are first onto a Lacquered surface with urushi (Rhus Verniciflua) sap and then sprinkled with gold and silver powder before the urushi dries. The history of this technique dates to the Heian period (794-1185).

Folded Letter-shaped Incense Container, Edo period, late 17th century to mid 18th century. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France.Makie (literally, "sprinkled picture") is a distinctive Japanese decorative technique in which designs are first onto a Lacquered surface with urushi (Rhus Verniciflua) sap and then sprinkled with gold and silver powder before the urushi dries. The history of this technique dates to the Heian period (794-1185).

Impressed by the beauty of lacquerware decorated in makie, Europeans who arrived on the shores of Japan during the Momoyama period (1573-1615) commissioned large quantities of works using this technique and returned to Europe with them.

Makie continued to be exported to Europe and other parts of Asia even under the policy of national isolation in the Edo period. In 1612, the fuedal Tokugawa Shogun closed Japan to the outside world excluding only limited trades of some crafts, silver and gold through the Dutch settlement at Dejima in Nagasaki. The Dutch East Indies Company exported some Japanese crafts in forms of lacquered chests, tables, shelves, and similar furniture to the West during Edo period (1602-1868).

These opulent treasures from the Far East symbolized wealth and power. Marie Antoinette, August the Strong (1670-1733), and other members of European royalty and nobility eagerly sought these objects and decorated their palaces and castles with them. The English were so fascinated by the resplendent beauty of this Japanese technique that in England makie came to be called "japan", just as "china" Chinese porcelain.

Marie Antoinette Collection in Versailles

"Marie Antoinette à la Rose", one of the most famous portraits of Marie Antoinette; it was meant to counteract the scandal caused by the "muslin" dress portrait, by Élisabeth Vigée-LebrunFrench queen Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) is a well-known collector of these rare Japanese crafts. Her "Makie" lacquerware collection is the largest and finest in Europe.

"Marie Antoinette à la Rose", one of the most famous portraits of Marie Antoinette; it was meant to counteract the scandal caused by the "muslin" dress portrait, by Élisabeth Vigée-LebrunFrench queen Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) is a well-known collector of these rare Japanese crafts. Her "Makie" lacquerware collection is the largest and finest in Europe.

Marie-Antoinette was born at the eastern edge of Europe into a family fascinated by all things Oriental. Her mother, Empress Maria-Theresa of Austria (1717-1780) often had herself painted in Turkish costume and had a large collection of Japanese lacquer boxes, declaring them to be more valuable to her than diamonds. On her death in 1780, she bequeathed some 50 boxes to Marie-Antoinette, who promptly commissioned Jean-Henri Riesener to make display shelves and cabinets for them. The Queen went on to collect more pieces (71 survive), many through the good offices of Dominique Daguerre.

Hen-shaped Tiered Box

Edo period, late 17th century to mid 18th century. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France. © Photo-RMN / © Thierry OllivierDaguerre was the most prominent marchand-mercier of the time, buying and commissioning items which he then sold on to wealthy clients. His records are a valuable resource when tracing provenance and he was especially diligent in the case of Marie-Antoinette's lacquer collection. In October 1789, when the Crown's assets were seized, he made an inventory which even records how and where the boxes were displayed. They were housed in the Queen's sitting room at Versailles, known as the cabinet doré. In 1783, she had the 1779 textile décor removed and replaced with sumptuous gilded paneling, in tune with her collection. Four tables, topped with petrified wood, bore the most precious items, including this sitting hen.

Hen-shaped Tiered Box

Edo period, late 17th century to mid 18th century. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France. © Photo-RMN / © Thierry OllivierDaguerre was the most prominent marchand-mercier of the time, buying and commissioning items which he then sold on to wealthy clients. His records are a valuable resource when tracing provenance and he was especially diligent in the case of Marie-Antoinette's lacquer collection. In October 1789, when the Crown's assets were seized, he made an inventory which even records how and where the boxes were displayed. They were housed in the Queen's sitting room at Versailles, known as the cabinet doré. In 1783, she had the 1779 textile décor removed and replaced with sumptuous gilded paneling, in tune with her collection. Four tables, topped with petrified wood, bore the most precious items, including this sitting hen.

Peach-shaped Incense Container. Edo period, late of 17th-middle of 18th century

Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France. © Photo-RMN / © Thierry OllivierThe collection forcused on small eighteeth-century lidded boxes in naturalistic shapes, such as gourds, dogs, and domestic fowl. It also included sets of five or six nested lacquerware boxes decorated with maki-e images; a jewel was often kept in the smallest, innermost box of the set. These collections were dispersed to Versailles, the Louvre, and Guimet Museum.

Peach-shaped Incense Container. Edo period, late of 17th-middle of 18th century

Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France. © Photo-RMN / © Thierry OllivierThe collection forcused on small eighteeth-century lidded boxes in naturalistic shapes, such as gourds, dogs, and domestic fowl. It also included sets of five or six nested lacquerware boxes decorated with maki-e images; a jewel was often kept in the smallest, innermost box of the set. These collections were dispersed to Versailles, the Louvre, and Guimet Museum.

Most of the boxes date from the first third of the eighteenth century and come from workshops in Kyoto or Nagasaki. They were made both for export and for the home market, the taste for lacquer being universal. That Marie-Antoinette made so much of her collection reflects both this taste and her deep attachment to her family. That she revamped the entire room to house them reflects the extravagance that has often been criticized. But the picture of a spendthrift Queen and a cautious King is far from the truth. Louis XVI commissioned freely from top cabinet makers such as Riesener, Jacob and Weisweiler and was notoriously indecisive. In addition, his aunts, the unmarried daughters of Louis XV, were anything but economical.

The most interesting characteristics of her collection is that it is not only consisted of small lacquered objects made for export but also refined pieces that were in demand by the Japanese.

Melon-shaped Inconse Container Edo period, late 17th century to mid 18th century. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France. © Photo-RMN / © Thierry OllivierIn Japan, until the early Edo period (early to mid-seventeenth century), all works in "Makie" were based on commission. However, at the end of the seventeenth century, as the merchant classes’ living standards rose dramatically, "Makie" came to be speculated for the market at large and sold in Kyoto lacquer shops for domestic consumers. Although these works were still expensive specialized commodities aimed at an elite group, the establishment of such a market reveals that the society of the time was remarkably affluent. Today, the core of "makie" collections in Japan consists of works that were made to order. Although Edo-period makie produced for the general domestic market have been included among these works, most of these have been thought to date to the nineteenth century or later. Similar works in overseas collections, starting with Marie Antoinette’s small lacquered objects, however, have revealed the existence of "makie" that were sold in town during the mid-Edo period. Hence, the major European collections have acted as a kind of time capsule for objects that were sold in Kyoto lacquer shops.

Melon-shaped Inconse Container Edo period, late 17th century to mid 18th century. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France. © Photo-RMN / © Thierry OllivierIn Japan, until the early Edo period (early to mid-seventeenth century), all works in "Makie" were based on commission. However, at the end of the seventeenth century, as the merchant classes’ living standards rose dramatically, "Makie" came to be speculated for the market at large and sold in Kyoto lacquer shops for domestic consumers. Although these works were still expensive specialized commodities aimed at an elite group, the establishment of such a market reveals that the society of the time was remarkably affluent. Today, the core of "makie" collections in Japan consists of works that were made to order. Although Edo-period makie produced for the general domestic market have been included among these works, most of these have been thought to date to the nineteenth century or later. Similar works in overseas collections, starting with Marie Antoinette’s small lacquered objects, however, have revealed the existence of "makie" that were sold in town during the mid-Edo period. Hence, the major European collections have acted as a kind of time capsule for objects that were sold in Kyoto lacquer shops.

Maria-Theresa Collection in Schönbrunn Palace

Archduchess Maria Theresa in 1727, by Andreas Möller. The flowers which she carries in the uplifted folds of her dress represent her fertility and expectations to bear children in adulthood.Her mother, Empress Maria-Theresa of Austria (1717-1780) was the most powerful patronage for Rococo style - our subject - Rococo Naturalism. Her own interest in Japanese lacquerware are clearly shown and preserved in her own Japanese lacquer collections in Schönbrunn Palace, Austria.

Archduchess Maria Theresa in 1727, by Andreas Möller. The flowers which she carries in the uplifted folds of her dress represent her fertility and expectations to bear children in adulthood.Her mother, Empress Maria-Theresa of Austria (1717-1780) was the most powerful patronage for Rococo style - our subject - Rococo Naturalism. Her own interest in Japanese lacquerware are clearly shown and preserved in her own Japanese lacquer collections in Schönbrunn Palace, Austria.

Madame de Pompadour Collection

Madame de Pompadour, portrait by François Boucher, 1756.Another famous collection of lacquerware is that of Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764) in Paris. She was also center figure of Rococo cultural movements.

Madame de Pompadour, portrait by François Boucher, 1756.Another famous collection of lacquerware is that of Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764) in Paris. She was also center figure of Rococo cultural movements.

I imagine that Japanese natularism appered on these lacquerware directly inspired the Rococo naturalism in France.

Seiji Yamauchi, 2009/11/29

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me