Tea in England

Introdution of Tea into England

Tea by George Dunlop Leslie (1835-1921) in 1885. A young woman in the dress of the 1700s -- a red polonaise dress over a flowered petticoat, a white fichu about her shoulders with a nosegay of yellow primroses tucked into it, and a beribboned mobcap -- standing behind a table covered with a white cloth. She is about to serve tea from a blue willow tea set. Cups with spoons, cream jug, and sugar bowl with lump sugar are all ready on a tray. Behind her is a wooden chair and a white panelled wall.The introduction of tea as a drink into England forms a chapter teeming with high adventure, strange peoples, and intriguing people. The first printed reference to tea in English, calling it “chaa”, appeared in 1598 in Jan Hugo van Linschooten’s Travels, an English translation of a work originally published in Holland in 1595-96.

Tea by George Dunlop Leslie (1835-1921) in 1885. A young woman in the dress of the 1700s -- a red polonaise dress over a flowered petticoat, a white fichu about her shoulders with a nosegay of yellow primroses tucked into it, and a beribboned mobcap -- standing behind a table covered with a white cloth. She is about to serve tea from a blue willow tea set. Cups with spoons, cream jug, and sugar bowl with lump sugar are all ready on a tray. Behind her is a wooden chair and a white panelled wall.The introduction of tea as a drink into England forms a chapter teeming with high adventure, strange peoples, and intriguing people. The first printed reference to tea in English, calling it “chaa”, appeared in 1598 in Jan Hugo van Linschooten’s Travels, an English translation of a work originally published in Holland in 1595-96.

An inventory of the plate and household furnishings in Peel Castle, Isle of Man, dated November 3, 1651, has been quoted as mentioning a “Tea Cupp Gilt”. This has been taken by some as indicating that tea was drunk in the Isle of Man previous to the year 1651. However antiquarian authorities in the office of the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office, London, agree that the first letter of the item of the inventory under discussion cannot be “T” and probably is “S”, the whole word being a contraction for “Silver Cupp Gilt”, they hold, would make sence, but one “Tea Cupp Gild” would not.

Dr. Thomas Short, 1690-1772, a Scottish physician and medical writer, is of the opinion that tea may have been known in England as far back as the reign of James I, because the first East India fleet sailed in 1601. But had the use of the leaf been known, it would seem that because of its novelty, it hardly would have escaped notice by the early English dramatists, whose works mirror the prevalent tastes and humors of their time.

It seems extraordinary that the English East India Company should not have discovered the possibilities of tea as early as did their commercial competitors the Dutch East India Company, who were bringing Chinese, as well as Japanese, tea with every ship in 1637. Yet it certainly was not known in England as early as 1641, for in a rare Treatise on Warm Beer, published in that year, the author undertakes to chronicle the advantages of the known hot drinks as opposed to cold, and mentions tea only by quoting the Italian Jesuit Father Maffei that, “they of China do for the most part drink the strained liquor of an herb called Chia hot”.

East India Company

Foundation

Batavia was a ship of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). It was built in Amsterdam in 1628, and armed with 24 cast-iron cannons. A twentieth century replica of the ship is also called the Batavia and can be visited in Lelystad, Netherlands.Soon after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, a group of London merchants presented a petition to Queen Elizabeth I for permission to sail to the Indian Ocean. The permission was granted and in 1591 three ships sailed from England around the Cape of Good Hope to the Arabian Sea. One of them, the Edward Bonaventure, then sailed around Cape Comorin and on to the Malay Peninsula and, subsequently, returned to England in 1594.

Batavia was a ship of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). It was built in Amsterdam in 1628, and armed with 24 cast-iron cannons. A twentieth century replica of the ship is also called the Batavia and can be visited in Lelystad, Netherlands.Soon after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, a group of London merchants presented a petition to Queen Elizabeth I for permission to sail to the Indian Ocean. The permission was granted and in 1591 three ships sailed from England around the Cape of Good Hope to the Arabian Sea. One of them, the Edward Bonaventure, then sailed around Cape Comorin and on to the Malay Peninsula and, subsequently, returned to England in 1594.

In 1596, three more ships sailed east; however, these were all lost at sea.

Two years later, on 24 September 1598, another group of merchants, having raised £30,133 in capital, met in London to form a corporation. Although their first attempt was not completely successful, they nonetheless set about seeking the Queen's unofficial approval, purchased ships for their venture, increased their capital to £68,373, and convened again a year later. This time they succeeded.

On 31 December 1600, the Queen granted a Royal Charter to "George, Earl of Cumberland, and 215 Knights, Aldermen, and Burgesses" under the name, Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies. The charter awarded the newly formed company, for a period of fifteen years, a monopoly of trade (known today as a patent) with all countries to the east of the Cape of Good Hope and to the west of the Straits of Magellan.

Sir James Lancaster commanded the first East India Company voyage in 1601.

Initially, the Company struggled in the spice trade due to the competition from the already well established Dutch.

In 1602 the Company did open a factory (trading post) in Bantam on the first voyage. and imports of pepper from Java were an important part of the Company's trade for twenty years. Bantam factory continued to be the centre of British trade in Indonesia until 1682.

In 1603 the Dutch East India Company also established a trading factory at Bantam. During the 17th century the Portuguese and Dutch fought for control of Bantam. Eventually the fact that the Dutch found that they could control Batavia (trading factory estd. 1611) more thoroughly than Bantam may have contributed to Bantam's decline.

The factory in Bantam was finally closed in 1683. During this time ships belonging to the company arrived in India, docking at Surat, which was established as a trade transit point in 1608.

In the next two years, it managed to build its first factory in the town of Machilipatnam on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. The high profits reported by the Company after landing in India (presumably owing to a reduction in overhead costs affected by the transit points), initially prompted King James I to grant subsidiary licenses to other trading companies in England.

But, in 1609, he renewed the charter given to the Company for an indefinite period, including a clause which specified that the charter would cease to be in force if the trade turned unprofitable for three consecutive years.

The Company was led by one Governor and 24 directors who made up the Court of Directors. They were appointed by, and reported to, the Court of Proprietors. The Court of Directors had ten committees reporting to it.

Expansion

The Company, benefiting from the imperial patronage, soon expanded its commercial trading operations, eclipsing the Portuguese Estado da India, which had established bases in Goa, Chittagong and Bombay (which was later ceded to England as part of the dowry of Catherine de Braganza).

The Company created trading posts in

- Surat (a factory was built in 1612),

- Madras (1639),

- Bombay (1668),

- Calcutta (1690).

By 1647, the Company had 23 factories, each under the command of a factor or master merchant and governor if so chosen, and 90 employees in India. The major factories became the walled forts of Fort William in Bengal, Fort St George in Madras and the Bombay Castle.

In 1634, the Mughal emperor extended his hospitality to the English traders to the region of Bengal (and in 1717 completely waived customs duties for the trade). The company's mainstay businesses were by now in cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre and tea.

All the while in 1650-56, it was making inroads into the Dutch monopoly of the spice trade in the Malaccan straits, which the Dutch had acquired by ousting the Portuguese in 1640-41.

In 1657, Oliver Cromwell renewed the charter of 1609, and brought about minor changes in the holding of the Company.

The status of the Company was further enhanced by the restoration of monarchy in England. By a series of five acts around 1670, King Charles II provisioned it with the rights to autonomous territorial acquisitions, to mint money, to command fortresses and troops and form alliances, to make war and peace, and to exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction over the acquired areas.

In 1711, the Company established a trading post in Canton (Guangzhou), China, to trade tea for silver.

First Englishman in Japan - William Adams

In 1600 the first Dutch ship from Java reached Japan. The Dutch ship De Liefde departed Rotterdam in 1598, on a trading voyage and attempted a circumnavigation of the globe. It was wrecked in Japan in 1600. The 24 survivors were received by Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) who questioned them at length on European politics and foreign affairs. Among them Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn (1560–1623), a native of Delft, and William Adams (1564–1620), English navigator, were selected to be a confidant of the Shogun on foreign and military affairs.

William Adams is believed to be the first Briton ever to reach that country. He was the inspiration for the character of John Blackthorne in James Clavell's bestselling novel Shogun.

William Adams became a key advisor to the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu and built for him Japan's first Western-style ships. Adams was later the key player in the establishment of trading factories by the Netherlands and England. He was also highly involved in Japan's Red Seal Asian trade, chartering and captaining several ships to Southeast Asia. He died in Japan at age 55, and has been recognized as one of the most influential foreigners in Japan during this period

Biography

William Adams descibed himself in his letter written in 1611;

…I am a Kentish man, born in a town called Gillingham, two English miles from Rochester, one mile from Chatham, where the King's ships do lie: from the age of twelve years old, I was brought up in Limehouse near London, being Apprentice twelve years to Master Nicholas Diggins; and myself have served for Master and Pilot in her Majesty's ships; and about eleven or twelve years have served the Worshipfull Company of the Barbary Merchants, until the Indish traffic from Holland began, in which Indish traffic I was desirous to make a little experience of the small knowledge which God had given me. So, in the year of our Lord 1598, I was hired for Pilot Major of a fleet of five sails, which was made ready by the Dutch Indish Company….

Voyage to Japan

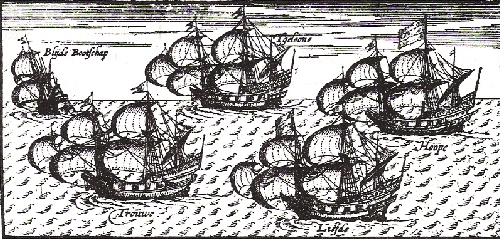

The Liefde, Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn and William Adams's ship. 17th century engravingAttracted by the Dutch trade with India, Adams, then 34 years old, shipped as pilot major with a five ship fleet dispatched from the isle of Texel to the Far East in 1598 by a company of Rotterdam merchants (a voorcompagnie, anterior to the Dutch East India Company). He set sail from Rotterdam in June 1598 on the Hoop and joined up with the rest of the fleet on June 24.

The Liefde, Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn and William Adams's ship. 17th century engravingAttracted by the Dutch trade with India, Adams, then 34 years old, shipped as pilot major with a five ship fleet dispatched from the isle of Texel to the Far East in 1598 by a company of Rotterdam merchants (a voorcompagnie, anterior to the Dutch East India Company). He set sail from Rotterdam in June 1598 on the Hoop and joined up with the rest of the fleet on June 24.

The fleet consisted of:

- the Hoop ("Hope"), under Jacques Mahu (1598), expedition leader, succeeded by Simon de Cordes (1599), and finally, Jan Huidekoper,

- the Liefde ("Love" or "Charity"), under Simon de Cordes, 2nd in command, succeeded by Gerrit van Beuningen and finally under Jacob Kwakernaak,

- the Geloof ("Faith"), under Gerrit van Beuningen, and in the end: Sebald de Weert,

- the Trouw ("Loyalty"), under Jurriaan van Boekhout (1599), and finally, Baltazar de Cordes,

- the Blijde Boodschap ("Good Tiding" or "The Gospel"), under Sebald de Weert, and later, Dirck Gerritz.

Originally, the fleet's mission was to sail for the west coast of South America, where they would sell their cargo for silver, and to head for Japan only if the first mission failed. In that case, they were supposed to obtain silver in Japan to buy spices in the Moluccas, before heading back to Europe. The vessels, ships ranging from 75 to 250 tons and crowded with men, were driven to the coast of Guinea, West Africa where the adventurers attacked the island of Annobón for supplies, and then moved on for the Straits of Magellan. Scattered by stress of weather and after several disasters in the South Atlantic, only three ships out of five made it through the Magellan Straits. (The Blijde Boodschap was adrift after being disabled in bad weather and was captured by the Spanish, whereas the Geloof returned to Rotterdam in July 1600 with 36 of the original 109 crew. During the voyage, William Adams had changed ships to the Liefde (originally Erasmus and adorned by a wooden Erasmus on her stern. The Liefde waited for the other ships at Floreana Island off the Chilean coast. However, only the Hoop had arrived by the spring of 1599 and the captains of both vessels, together with Adams's brother Thomas and twenty other men, lost their lives in an encounter with the natives. The Trouw later turned up in Tidore (Indonesia) where the crew was eliminated by the Portuguese in January 1601. In fear of the Spaniards, the remaining crews determined to sail across the Pacific. It was late November 1599 when the two ships sailed westwardly for Japan. On their way, the two ships made landfall in "certain islands" (possibly the islands of Hawaii) where eight sailors deserted the ships. Later during the voyage, a typhoon claimed the Hoop with all hands, in late February 1600.

On April 19, 1600, after more than nineteen months at sea, the Liefde with a crew of about twenty sick and dying men (out of an initial crew of about 100) was brought to anchor off Usuki 臼杵 in Bungo 豊後 (current Ooita 大分 prefecuture), eastern part of the Kyushu island of Japan. Its cargo consisted of eleven chests of coarse woolen cloth, glass beads, mirrors, spectacles, nails, iron, hammers, 19 bronze cannons, 5,000 cannonballs, 500 muskets, 300 chain-shot and 3 chests filled with coats of mail. When the nine crew members were strong enough to stand, they made landfall off Sashiu coast 佐志生海岸 in Usuki 臼杵, they were met by locals and Portuguese Jesuit priests claiming that Adams' ship was a pirate vessel and that the crew should be crucified as pirates.

The ship was seized and the sickly crew were imprisoned at Osaka Castle on orders by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the daimyo of Mikawa and future Shogun. The 19 bronze cannons of the Liefde were unloaded and according to Spanish accounts later employed at the decisive Battle of Sekigahara on October 21, 1600.

Great Engineer and Mathematician

William Adams met Tokugawa Ieyasu in Osaka castle three times between May and June 1600. He was questioned by Ieyasu, then a guardian of the young son of the Taiko, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the ruler who had just died. His knowledge of ships, shipbuilding and nautical smattering of mathematics appealed to Ieyasu.

William Adams described the situation in a letter to his wife;

Coming before the king, he viewed me well, and seemed to be wonderfully favorable. He made many signs unto me, some of which I understood, and some I did not. In the end, there came one that could speak Portuguese. By him, the king demanded of me, of what land I was, and what moved us to come to his land, being so far off. I showed unto him the name of our country, and that our land had long sought out the East Indies, and desired friendship with all kinds and potentates in way of merchandise, having in our land diverse commodities, which these lands had not … Then he asked whether our country had wars? I answered him yea, with the Spaniards and Portugals, being in peace with all other nations. Further, he asked me, in what I did believe? I said, in God, that made heaven and earth. He asked me diverse other questions of things of religion, and many other things: as what way we came to the country. Having a chart of the whole world, I showed him, through the Strait of Magellan. At which he wondered, and thought me to lie. Thus, from one thing to another, I abode with him till midnight.

Adams further explained that Ieyasu finally denied the Jesuits' request for punishment on the ground that:

we as yet had not done to him nor to none of his land any harm or damage; therefore against Reason or Justice to put us to death. If our country had wars the one with the other, that was no cause that he should put us to death; with which they were out of heart that their cruel pretence failed them. For which God be forever praised.

In 1604, Tokugawa Ieyasu ordered William Adams and his companions to help Mukai Shogen, who was commander in chief of the navy of Uraga, build Japan's first Western-style ship. The sailing ship was built at the harbour of Ito on the east coast of the Izu Peninsula, with carpenters from the harbour supplying the manpower for the construction of an 80 ton vessel which was employed to survey the Japanese coast. The Shogun then ordered a larger 120 tons ship to be built the following year; (the Liefde was 150 tons). According to Adams, Tokugawa "came aboard to see it, and the sight whereof gave him great content". In 1610, the 120-ton ship (later named San Buena Ventura) was lent to shipwrecked Spanish sailors, who sailed back to Mexico with it, accompanied by a mission of 22 Japanese led by Tanaka Shosuke.

Other survivors of the Liefde were also rewarded with favours and even allowed to pursue foreign trade. Most of the original crew were able to leave Japan in 1605 with the help of the daimyo of Hirado. However William Adams did not himself receive permission to leave Japan until 1613. Among the crews, Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn and Melchior van Santvoort engaged in trade between Japan and Southeast Asia.

Around 1608 William Adams contacted the interim governor of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco (1564–1636) on behalf of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who wished to establish direct trade contacts with New Spain. Friendly letters were exchanged, officially starting relations between Japan and New Spain.

William Adams is also recorded as having chartered Red Seal Ships during his later travels to Southeast Asia. The Ikoku Tokai Goshuinjo has a reference to Miura Anjin receiving a shuinojo, a document bearing a red Shogunal seal authorizing the holder to engage in foreign trade, in 1614.

First Samurai Briton

The shogun took a liking to William Adams and made him a revered diplomatic and trade advisor and bestowed great privileges upon him. Ultimately, Adams became his personal advisor on all things related to Western powers and civilization and, after a few years, Adams replaced the Jesuit Padre João Rodrigues as the Shogun's official interpreter. Padre Valentim Carvalho wrote: "After he had learned the language, he had access to Ieyasu and entered the palace at any time"; he also described him as "a great engineer and mathematician".

William Adams had a wife and children in England but Tokugawa Ieyasu had forbidden the Englishman to leave Japan. He was presented with two swords representing the authority of a Samurai. The Shogun decreed that William Adams the pilot was dead and that Miura Anjin (三浦按針), a samurai, was born. This made Adams's wife in England in effect a widow (although Adams managed to send regular support payments to her after 1613 via the English and Dutch companies) and "freed" Adams to serve the Shogunate on a permanent basis. Adams also received the title of hatamoto (bannerman), a high-prestige position as a direct retainer in the Shogun's court.

He was provided with generous revenues: "For the services that I have done and do daily, being employed in the Emperor's service, the emperor has given me a living" (in his letters). He was granted a fief in Hemi 逸見 within the boundaries of present-day Yokosuka City, "with eighty or ninety husbandmen, that be my slaves or servants". His estate was valued at 250 koku (a measure of the yearly income of the land in rice, with one koku defined as the quantity of rice sufficient to feed one person for one year). He finally wrote "God hath provided for me after my great misery" by which he meant the disaster-ridden voyage that had initially brought him to Japan.

Adams's estate was located next to the harbour of Uraga, the traditional point of entrance to Edo Bay, where he is recorded to have dealt with the cargoes of foreign ships. John Saris related that when he visited Edo in 1613, Adams was in possession of the reselling rights for the cargo of a Spanish ship at anchor in Uraga Bay.

Adams' position gave him the means to marry Oyuki お雪, the daughter of Magome Kageyu, a highway official who was in charge of a packhorse exchange on one of the grand imperial roads that led out of Edo (roughly present day Tokyo). Although Magome was important, Oyuki was not of noble birth, nor high social standing, so it was likely that Adams married out of true affection rather than for social reasons. Adams and Oyuki had a son called Joseph and a daughter named Susanna. Adams however found it hard to rest his feet and was constantly on the road. Initially, it was in the vain attempt to organize an expedition in search of the Arctic passage that had eluded him previously.

William Adams had a high regard for Japan, its people, and its civilization:

The people of this Land of Japan are good of nature, curteous above measure, and valiant in war: their justice is severely executed without any partiality upon transgressors of the law. They are governed in great civility. I mean, not a land better governed in the world by civil policy. The people be very superstitious in their religion, and are of diverse opinions. (William Adams's letter to Bantam, 1612)

Establishment of the Dutch East India Company in Japan

The Liefde's captain, Jacob Quaeckernaeck, and the treasurer, Melchior van Santvoort, were also sent by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1604 on a shogun-licensed Red Seal Ship to Patani in the Malay Peninsula to contact the Dutch United East India Company (Dutch : Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) trading factory which had just been established there in 1602, to bring more western trade to Japan and break the Portuguese monopoly on Japan's external trade. In 1605, William Adams obtained a letter from Tokugawa Ieyasu formally inviting the Dutch to trade with Japan.

Hampered by conflicts with the Portuguese and limited resources in Asia, the Dutch were not able to send ships until 1609. 11 ships sailed from Texel in 1607 under the command of Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff(1573-1609). After arriving in Bantam, two ships which were dispatched to establish the first official trade relations between the Netherlands and Japan. Two Dutch ships, commanded by Jacques Specx (1585-1652), arrived in Japan on July 2, 1609;

- De Griffioen (the "Griffin", 19 cannons)

- Roode Leeuw met Pijlen (the "Red lion with arrows", 400 tons, 26 cannons),

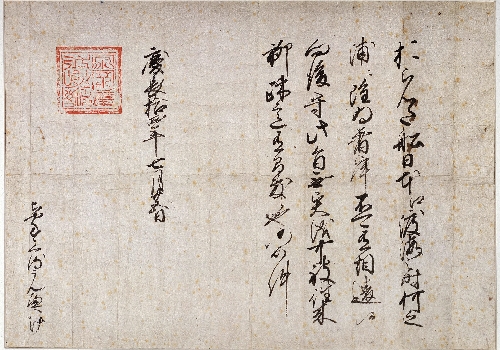

Red Sealed Trade Pass for Dutch, issued in the name of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the Japan Shogun. The text commands: "Dutch ships are allowed to travel to Japan, and they can disembark on any coast, without any reserve. From now on this regulation must be observed, and the Dutch left free to sail where they want throughout Japan. No offenses to them will be allowed, such as on previous occasions" - dated August 24, 1609 with the red-seal of the Shogun.Among the crews Chief merchants Abraham van den Broeck and Nicolaas Puyck, two Dutch envoys, were the official bearers of a letter from Prince Maurice of Nassau (1567–1625) to the court of Edo. Melchior van Santvoort (1570–1641) acted as the Dutch envoy mission's interpreter, who was a surviving crew of the Dutch ship De Liefde and continued to being active in trades between Japan and Southeast Asia based in Nagasaki. William Adams negotiated on behalf of these emissaries.

Red Sealed Trade Pass for Dutch, issued in the name of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the Japan Shogun. The text commands: "Dutch ships are allowed to travel to Japan, and they can disembark on any coast, without any reserve. From now on this regulation must be observed, and the Dutch left free to sail where they want throughout Japan. No offenses to them will be allowed, such as on previous occasions" - dated August 24, 1609 with the red-seal of the Shogun.Among the crews Chief merchants Abraham van den Broeck and Nicolaas Puyck, two Dutch envoys, were the official bearers of a letter from Prince Maurice of Nassau (1567–1625) to the court of Edo. Melchior van Santvoort (1570–1641) acted as the Dutch envoy mission's interpreter, who was a surviving crew of the Dutch ship De Liefde and continued to being active in trades between Japan and Southeast Asia based in Nagasaki. William Adams negotiated on behalf of these emissaries.

The Dutch obtained free trading rights throughout Japan (in contrast, the Portuguese were only allowed to sell their goods in Nagasaki at fixed, negotiated prices) and to establish a trading factory in Japan. The Hollandes be now settled in Japan and I have got them that privilege as the Spaniards and Portingals could never get in this 50 or 60 years in Japan. (William Adams letter to Bantam).

After obtaining this trading right through an edict of Tokugawa Ieyasu on August 24, 1609, the Dutch inaugurated a trading factory in Hirado on September 20, 1609. In September 1609 the ship's Council decided to hire a house on Hirado island (west of the southern main island Kiushu) and established a trading factory of Dutch East Indian Company there. Jacques Specx became the first "Opperhoofd", a Chief of the new Company's factory.

The "trade pass" (Dutch: Handelspas) was kept preciously by the Dutch in Hirado and then Dejima as a guarantee of their trading rights, during the following two centuries of their presence in Japan.

Establishment of an English trading factory

In 1611, news came to William Adams of an English settlement in Bantam, Indonesia, and he sent a letter asking them to give news of him to his family and friends in England and enticing them to engage in trade with Japan which "the Hollanders have here an Indies of money" (Adams's letter to Bantam).

In 1613, the English captain John Saris(1580 – 1643) arrived at Hirado in the ship Clove with the intent of establishing a trading factory for the British East India Company (Hirado was already a trading post for the Dutch East India Company (the VOC)). Adams met with Saris's ire over his praise of Japan and adoption of Japanese customs:

He persists in giving "admirable and affectionated commendations of Japan. It is generally thought amongst us that he is a naturalized Japaner." (John Saris)

One of the two Japanese suits of armor presented by Tokugawa Hidetada to John Saris for King James I in 1613, which displayed in the Tower of London since 1660.In Hirado, William Adams refused to stay in English quarters and instead resided with a local Japanese magistrate. It was also commented that he was wearing Japanese dress and spoke Japanese fluently. Adams estimated the cargo of the Clove was of little value, essentially broadcloth, tin and cloves (acquired in the Spice Islands), saying that "such things as he had brought were not very vendible".

One of the two Japanese suits of armor presented by Tokugawa Hidetada to John Saris for King James I in 1613, which displayed in the Tower of London since 1660.In Hirado, William Adams refused to stay in English quarters and instead resided with a local Japanese magistrate. It was also commented that he was wearing Japanese dress and spoke Japanese fluently. Adams estimated the cargo of the Clove was of little value, essentially broadcloth, tin and cloves (acquired in the Spice Islands), saying that "such things as he had brought were not very vendible".

William Adams travelled with John Saris to Shizuoka where they met with Tokugawa Ieyasu at his principal residence in September and then continued to Kamakura where they visited the famous Buddha (the 1252 Daibutsu on which the sailors etched their names) before moving on to Edo where they met Ieyasu's son Tokugawa Hidetada (1579—1632) who was now nominally Shogun even though Ieyasu retained most of the actual decision-making powers. During that meeting, Hidetada gave John Saris two varnished suits of armour for King James I(1566–1625), today housed in the Tower of London. The suits were made by Iwai Yozaemon of Nambu. They were part of a series of presentation armours of ancient 15th century Dō-maru style.

On their way back, they again visited Tokugawa Ieyasu, who conferred trading privileges to the English through a Red Seal permit giving them "free license to abide, buy, sell and barter" in Japan. The English party headed back to Hirado on October 9, 1613.

On this occasion, William Adams asked for and obtained Tokugawa's authorization to return to his home country. However, he ultimately declined Saris' offer to bring him back to England: "I answered him I had spent in this country many years, through which I was poor... [and] desirous to get something before my return". His true reasons seem to lie rather with his profound antipathy for Saris: "The reason I would not go with him was for diverse injuries done against me, which were things to me very strange and unlooked for." (William Adams letters)

William Adams accepted employment with the newly founded Hirado trading factory of the East Indian Comapny, signing a contract on November 24, 1613, becoming an employee of the East India Company for the yearly salary of 100 English Pounds, more than double the regular salary of 40 Pounds earned by the other factors at Hirado. Adams was to take a leading part, under Richard Cocks, the head of the Hirado factory, and together with six other compatriots (Tempest Peacock, Richard Wickham, William Eaton, Walter Carwarden, Edmund Sayers and William Nealson), in the organization of this new English settlement.

William Adams had actually advised against the choice of Hirado, which was small and far away from the major markets in Osaka and Edo, and instead had recommend to Saris, in vain, that they should select Uraga near Edo.

During the ten year activity of the company between 1613 and 1623, apart from the first ship (the Clove in 1613), only three other English ships brought cargoes directly from London to Japan, invariably described as poor value on the Japanese market. The only trade which helped support the factory was that organized between Japan and South-East Asia and mainly undertaken by William Adamsselling Chinese goods for Japanese silver:

Were it not for hope of trade into China, or procuring some benefit from Siam, Pattania and Cochin China, it were no staying in Japon, yet it is certen here is silver enough & may be carried out at pleasure, but then we must bring them commodities to their liking. (Richard Cocks Diary, 1617)

First Reference of Tea by an Englishman in 1615

The earliest known reference to tea by an Englishman is found in a letter preserved in the archives of the East India Company – now at the India office, London, S. W. Mr. R. Wickham, the agent for the company at “Firando” (Hirado), Japan, wrote to Mr. Eaton, another agent of the company, at Macao, China, on June 27, 1615, requesting him to forward to the writer “a pot of the best sort of chaw”.

Given the facts that William Adams arrived at Japan in 1600 and he invited John Saris and successfuly got the Red Seal permission for the East Indain Company in 1613, this reference leads us to the conclusion that some Englishman knew about tea as early as 1615. However they did not think about the trading of Tea, rather they enjoyed tea as precious private soveniour.

In 1613 Japanese Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada gave John Saris two varnished suits of armour for King James I which is still displayed in the tower of London today. It is naturali that tea was also send to James I as a soveniour.

As yet there was no word for tea in the English language, so early British authors were wont to employ some approximation of its Chinese name, “ch’a”. Tea appears as chia in "Purchas His Pilgrimes" by Samuel Purchas (1575-1626) in 1625. To quote from this early English collector of travels: “They use much the powder of a certain herbe called chia of which they put as much as a Walnut shell may containe, into a dish of Porcelane, and drink it with hot water.” In a footnote Purchas observes that chia is used “in all entertainments in Iapon and China.”

In 1637, the English first appeared in the Orient, when a fleet of four ships entered the mouth of the Canton river, and, with characteristics aggressiveness, forced their way past the Portuguese, who opposed them at Macao. Upon reaching Canton, they established direct contact with Chinese merchants. There is no record to show that any tea was transported at this time, however, nor upon the occasion of a second visit of the English at Macao, which occurred twenty-seven years later.

Spelling of T-e-a

Shortly after 1644, English traders established themselves at the port of Amoy, which was their principal Chinese base for nearly a century. Here they picked up from the Fukien dialect the word t’e (“tay”) for the drink used by the Chinese, and they spelled it t-e-a, writing ea as a diphthong, oe, having the sound of long a.

First Public Sale at Garway's in 1657

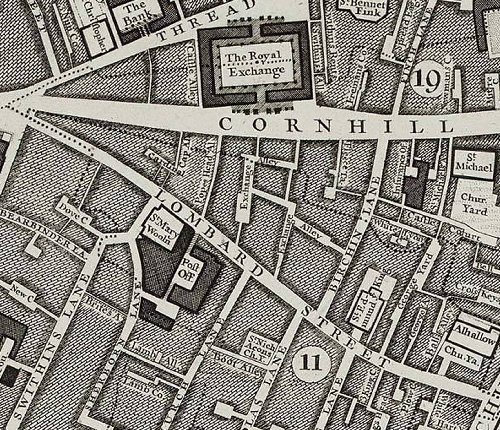

John Rocque's Map in 1747. The coffee houses of Exchange Alley, especially Jonathan's and Garraway's, became an early venue for the lively trading of stocks and commodities. These activities were the progenitor of the London Stock Exchange. Similarly, Edward Lloyd's coffee house, at 16, Lombard Street but originally on Tower Street, was the forerunner of Lloyd's of London.

There is no record of the earliest importation of tea into England. Probably this occurred more or less contemporaneously with its appearance in Holland, France, and Germany, sometime about the middle of the seventeenth century.

John Rocque's Map in 1747. The coffee houses of Exchange Alley, especially Jonathan's and Garraway's, became an early venue for the lively trading of stocks and commodities. These activities were the progenitor of the London Stock Exchange. Similarly, Edward Lloyd's coffee house, at 16, Lombard Street but originally on Tower Street, was the forerunner of Lloyd's of London.

There is no record of the earliest importation of tea into England. Probably this occurred more or less contemporaneously with its appearance in Holland, France, and Germany, sometime about the middle of the seventeenth century.

From a broadside by a London coffee house keeper, one Thomas Garway, or Garraway, we learn that previous to the year 1657 the leaf and drink had been used only “as a regalia in high treatments and entertainments, and presents made thereof to princes and grandees.” For such use purchasers were compelled to pay GBP 6 to GBP 10 ($30 to $ 50 in 1935) per pound, and to get their supplies abroad, as tea was not as yet sold in Britain.

This Garway's broadsheet, broadside, or shop-bill, entitled "An Exact Description of the Growth, Quality and Vertues of the Leaf Tea", ca. 1660, preserved in the British Museum.

The same broadside tells us that in 1657 the tea leaf and beverage were first publicly sold in England by Thomas Garway, tobacconist and coffee house keeper at his place in Exchange Alley. This famous coffee house known to succeeding generations as “Garraway's”, was a center for great mercantile transactions. Hence men prominent in the commercial life of the metropolis were wont to refresh themselves with ale, punch, brandy arrack, etc., in addition tea and coffee.

The tea sold by Garway was reputed to possess remarkable preventive and curative qualities, but there was little general knowledge of it in London; so Garway sought directions for making the beverage from the best-informed merchants and travelers from the East, preparing it accordingly. For the benefit of customers who desired to make the drink in their homes or elsewhere, he offered to sell all comers the prepared leaf at 16s. ($4) to 60s. ($15) a pound, thus effecting a saving of from 104s. ($26) to 140s. ($35) per pound. Having established a fair price, he proceeded to herald the quality and virtues of tea in the broadside which has assumed historical importance as one of the earliest and most effective advertisements for tea.

The First Tea Advertisement by the Sultaness-head Cophee-house in 1658

The Sultaness Head Coffee House was one of the earliest to adopt the tea beverage as a part of its entertainment, and on September 30, 1658, its proprietor inserted the first newspaper advertisement of tea, in Mercurius Politicus. This advertisement announced:

That Excellent and by all Physitians approved China drink, called by the Chineans Tcha, by other Nations Tay, alias Tee, is sold at the the Sultaness-head Cophee-house in Sweeting's Rents by the Royal Exchange, London.

The tokens for the coffee-house bore the Sultaness' veiled head. Its origins are otherwise obscure, other than it may have moved to the site of Morat Ye Great after its destruction in the Great Fire. The Sultaness Coffee House was also mentioned by Charles Dickens (1812-1870) in a number of his works, notably Little Dorrit, and this implies the survival of this particular coffee-house for about two hundred years.

About this time tea was everywhere offered and accepted as a wonderful health drink. Quite possibly there may have been a bit of favorable psychology in this, for men have ever been fond of attributing remedial values to their drinks, and tea was soon to be acclaimed “the sovereign drink of pleasure and of health”.

The world’s three great temperance rinks gained a quick popularity in the London coffee houses, for we read in Thomas Rugge's Mercurius Politicus Redivivus or, A Collection of the most materiall occurrances and transactions in Public Affairs since Anno Dni, 1659, untill 28 March, 1672, serving as an annuall diurnall for future satisfaction and information of November 14, 1659:

Theire ware also att this time a Turkish drink to bee souldm almost in every street, called Coffee, and a nother kind of drink called Tee, and also a drink called Chacolate. Which was a very harty drink.

Tea was sold also at Jponathan’s, another coffee house in Exchange Alley. In the play A Bold Strike for a Wife written by Susanna Centlivre (1667-1723) in 1717, the author laid one of its scenes at Jonathan’s;

and while the business of the place is being enacted, she makes the serving lads cry, “Fresh coffee, gentleman! Fresh Coffee! Bohea tea, Gentleman!

The First Tea Broadside by Thomas Garway, ca. 1660

Garway observes in the quaint advertising copy of the period:

The leaf is of such known vertues, that those very Nations famous for Antiquity, Knowledge, and Wisdom, do frequently sell it among themselves for twice its weight in silver, and high estimation of the Drink made therewith hath occasioned an inquiry into the nature thereof amongst the most intelligent persons of all Nations that have travelled in those parts, who after exact Tryal and Experience by all ways of imaginable, have commended it to the use of their several Countries, for its Vertues and Operations, particularly as followeth, viz: The Quality is moderately hot, proper for Winter or Summer. The Drink is declared to be most wholesome, preserving in perfect health until extreme Old Age.

Garway enumerates “the particularly Vertues” as follows:

It maketh the body active and lusty.

It helpeth the Headache, giddiness and heaviness thereof.

It removeth the obstructions of the Spleen.

It is very good against the Stone and Gravel, cleaning the Kidneys and Uriters, being drank with Virgins Honey instead of Sugar.

It taketh away the difficulty of breathing, opening Obstructions.

It is good against Lipitude Distillations and cleareth the Sight.

It removeth Lassitude, and cleanseth and purifyeth adult Humors and hot Liver.

It is good against Crudities, strengthening the weakness of the Ventricle or Stomack, causing good Appetite and Digestion, and particularly Men of a corpulent Body, and such as are great eaters of Flesh.

It vanquisheth heavy dreams, easeth the Brain, and strengtheneth the Memory.

It overcometh superfluous Sleep, and prevents Sleepiness in general, a draght of the Infusion being taken, so that without trouble whole nights may be spent in study without hurt to the Body, in that it moderately heateth and bindeth the mouth of the Stomack.

It prevents and cures agues, Surfets and Feavers, by infusing a fit quantity of the Leaf, thereby provoking a most gentile Vomit and breathing of the Pores, and hath been given with wonderful success.

It (being prepared with Milk and Water) strengtheneth the inward parts, and prevents Consumptions, and powerfully assuageth the pains of the Bowels, or griping of the Guts and Looseness.

It is good for Colds, Dropsies and Scurveys, if properly infused, purging the Blood by sweat and Urine, and expelleth infection.

It drives away all pains in the Collick proceeding from Wind, and purgeth safely the Gall.

And that the Vertues and excellencies of this Leaf and Drink are many and great is evident and manifest by the high esteem and use of it (especially of late years) among the Physitians and knowing men n France, Italy, Holland and other parts of Christendo.

Who of Garway's patrons, having a corpulent body, a weak “stomack”, ailing “uriters”, or whatnot, but would daily seek the protection of this panacea from out the purple East, after reading the claims that were made for it in this remarkable broadside? Much editorial credit, indeed, is due Garway for the diligence by which he contrived to boil down into the limits of a single sheet practically all the claims, fantastic or otherwise, that had been made for tea as a medicine in the writings of the Chinese, or of the early Jesuit missionaries in the Far East.

The Povey Manuscript, 1686

Just what claims for tea were coming to England from the East is made clear by a manuscript now in the British Museum, which was elegantly transcribed in 1686 from a paper of T. Povey, M.P. and Civil Servant, being a translation of a Chinese encomium. It reads:

1. It has according to the description (being translated out of the Chinese Language), these following Virtues:

2. It purifies the Bloud of that which is grosse and Heavy.

3. It Vanquisheth heavy Dreams.

4. It Easeth the brain of heavy Damps.

5. Easeth and cureth giddiness and Paines n the Heade.

6. Prevents the Dropsie.

7. Drieth Moist humours in the Head.

8. Consumes Rawness.

9. Opens Obstructions.

10. Cleares the Sight.

11. Clenseth and Purifieth adult humours and a hot Liver.

12. Purifieth defects of the Bladder and Kiddneys.

13. Vanquisheth Superfluous Sleep.

14. Drives away dissines, makes one Nimble and Valient.

15. Encourageth the heats and Drives away feare.

16. Drives away all Paines of the Collick which proceed from Wind.

17. Strengthens the Inward parts and Prevents Consumptions.

18. Strengthens the Memory.

19. Sharpens the Will and Quickens the Understanding.

20. Purgeth safely the Gaul.

21. Strengthens the use of due benevolence.

Transcribed from a paper of Tho. Povey, Esq., Oct. 20, 1686.

Prominent men in the social and religious life of Britain were much intrigued by the new China drink. A letter from Daniel Sheldon, factor for the English East India Company at Balsore, written in 1659 to another factor for the company at Bandel, urgently requested a sample of tea to send home to his uncle, the illustrious Dr. Gilbert Sheldon, Archbishop of Canterbury. He wrote:

I must desire you to procure the chaw, if possible. I care not what it cost. "Tis for a good uncle of mine, Dr. Sheldon, whome some body hath persweded to studdy the divinity of that herbe, leafe, or what else it is; and I am soe obliged to satisfy this curiosity that I could willingly undertake a viage to Japan or China to doe it.

There seems to have been some difficulty in securing the tea at Bandel, for Sheldon wrote again:

For God's sake, good or badd, buy the chaw if it is to be sold. Pray favor me likewise with advise what 'tis good for, and how to be used.

The final outcome is not revealed by the correspondence, but, whatever this may have been, it is not likely that the Archbishop's curiosity long went unsatisfied, as tea had then on sale in London for several years.

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me