Paul de Lamerie (1688-1751)

Biography

Mountrath ewer and dish, marked by Paul de Lamerie, arms of Mountrath, 1742, Gilbert Collection. Comprising of a helmet-shaped ewer, stands on a shaped circular foot chased with flowers, waves, and a lizard; the stem is modelled as a kneeling putto. The body of the ewer is chased with a figure of Neptune in a seascape and with scrolls, clouds, and personifications of the winds; A coat of arms applied beneath the shaped lip. The handle is formed as a female demifigure rising from flowers and scrolls, holding a shell in her left hand. The large, shaped circular dish (with later applied) coat of arms to the centre, the border chased in high relief with a broad band of ornament incorporating figures of Jupiter, Diana, and two putti (a representation of a small child, often naked and having wings; *plural, putto), with elaborate surrounds of scrolls, masks, shells, and flowers.On 14 April 1688 Paul Jacques de Lamerie, a son of Paul Souchay de la Merie and Constance nee Roux, Huguenots, was baptized at the Waloon Church in Bois-le-Duc (modern 's Hertogenbosch), Holland. The Waloon Church (French: Église Wallonne; Dutch: Waalse kerk) is Calvinist church building in the Netherlands and its former colonies whose members originally came from the Southern Netherlands and France and whose native language is French. Members of these churches belong to the Walloon Reformed Church which is long-distinguished from the Low German or Dutch-speaking Dutch Reformed Church.

His father, Paul Souchay de la Merie, had been a officer in the army of William III of Orange (1650-1702) after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes expelled the Huguenots from France in 1685. In February 1686, he was paid off and released from the army along with many others.

By the time they had their only son baptized, they had made the decision to leave the Netherlands and follow William III of Orange to England during the Glorious Revolution of 1688. This fact was evidenced by their request for a copy of his entry in the baptismal register which would be needed to prove their son's identity on arrival in England.

He was brought to England by his parents at the age of eleven and a half months. The family settled in Berwick Street in the heart of Soho, the district having been taken over mostly by French Huguenot refugees.

On 24 June 1703 he was endenizened with his father. Denization is an obsolete process in English Common Law, dating from the 13th century, by which a foreigner became a denizen, gaining some privileges of a British subject, including the right to hold English land. Denization occurred by a grant of letters patent, an exercise of the royal prerogative and denizens paid a fee and took an oath of allegiance to the crown. The de Lameries had never applied to be denizened without funds however it was necessary to endenize to allow young Paul de Lamerie to take up an apprenticeship.

Wine Fountain by Pierre Plate, 1713. H: 64cm, W: 41.4cm, 12.8kg. This wine fountain would have been prominently displayed on a sideboard. It was used to rinse wine glasses before they were refilled to guests at the dining table. The maker, Pierre Platel, was a prestigious Huguenot goldsmith to whom Paul de Lamerie, later the most successful smith in London, was apprenticed. Victoria & Albert Museum.On 6 August 1703 he aprenticed without premium to Huguenot silversmith Pierre Platel, when his father is described as 'Of the perish of St. Anne's Westminster Gent'. His father applied to the Huguenot relief fund (a community church-based charity) for the £6 he had to hand over to Pierre Platel to take Paul de Lamerie on. Only when the money had been obtained did Platel sign the indenture of apprenticeship.

Wine Fountain by Pierre Plate, 1713. H: 64cm, W: 41.4cm, 12.8kg. This wine fountain would have been prominently displayed on a sideboard. It was used to rinse wine glasses before they were refilled to guests at the dining table. The maker, Pierre Platel, was a prestigious Huguenot goldsmith to whom Paul de Lamerie, later the most successful smith in London, was apprenticed. Victoria & Albert Museum.On 6 August 1703 he aprenticed without premium to Huguenot silversmith Pierre Platel, when his father is described as 'Of the perish of St. Anne's Westminster Gent'. His father applied to the Huguenot relief fund (a community church-based charity) for the £6 he had to hand over to Pierre Platel to take Paul de Lamerie on. Only when the money had been obtained did Platel sign the indenture of apprenticeship.

Pierre Platel (1664-1719), born as a member of an aristocratic family in Lille, arrived in England along with his brother in 1688, after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. In 1699 he registered his mark as a 'largeworker' by Redemption, i.e by payment rather than by serving his apprentiship at Goldsmiths' Hall. A leading craftsman and member of the London Huguenot silversmithing community, a French expatriate group known for its advanced technical expertise. Pall Mall 'over by the Duke of Schomberg' where Pierre Platel set up his shop (and he probably lived there) was a remarkable address, testifying to his business acumen and solid finances. Platel apprenticed only four boys during his working life and it was enigma why he agreed to take on Paul de Lamerie, aged 15, on the 24th of June 1703.

Based on Pierre Platel's tutelage Lamerie created silver of exceptional craftsmanship.

In 1711 he had served his time. He started to work on as a journeyman at Pierre Platel' shop while he saved money and made arrangements to receive his freedom by service. During the period until his mark registered, there were some invoices proving that Paul de Lamerie was dotting about London selling large and expensive silver items to the nobility. Paul de Lamerie, at age 25, already established excellent customer relationship with high net worth individuals serving in Platel's shop at Pall Mall.

In 1712 he became a Freeman of the City of London.

On 4 February 1713 Paul de Lamerie became Free and registered his mark at Goldsmiths' Hall, which was formed from the first two letters of his surname "LA" surmounted by a crown and a fleur-de-lis below reflected his French origin, with his address "Windmill Street, near the Haymarket".

In 1714 the court at Goldsmith' Hall fined him £20 (worth over 3000 pounds now) because of his duty dodging. At that time every ounce of silverware passed for hallmarking at Assay office was taxed by the government, one of the few taxes at the time, and this tax was bitterly resented by both goldsmiths and their customers. A large amount of pieces by Paul de Lamerie are not marked other than with his own maker's mark, proving he was avoiding the duty and selling to people who trusted him to provide them with objects of superior fineness. Futhermore he didn't make silverware by himself, rather he took in work from anonymous French silversmiths working in the back streets of London and had it hallmarked as his own. By the summer of 1715, he was back up before the court because he 'covered Foreigners work and got ye same toucht at ye Hall'. Other Huguenot goldsmiths got into trouble for this too, but no one on the scale of Lamerie. He was up before the court for it again in 1716.

His duty dodging system organizing foreigners silversmiths and his customers made considerable money for him.

Within 4 years after his mark registration, he had established him sufficiently to open a shop and workshop at the sign of the Golden Ball in Windmill Street. Taking on 13 apprentices between the periods of 1716 to 1749. His stock now included jewellery as well as Silverware of which he continued to make traditional plain designs of the English Queen Anne style.

In 1716 he was appointed as a Goldsmith to the King (Major-General H. W. D. Sitwell. 'The Jewell House and the Royal Goldsmiths' Arch. Journ. CXVII, p. 152). In 1717 he was again charged with 'making and selling Great quantities of Large Plate which he doth not bring to Goldsmiths' Hall to be mark't according to Law.' He was undoubtedly convinced criminal.

On 11 February 1717 at the age of 28, he married Louise Jolliott of St. Giles in the Fields, at Glasshouse Street Church with licence of Archbishop of Canterbury. He applied, through the Vicar-General's office, to the Archbishop of Canterbury for what today would be called a special marriage licence. The application for a licence means Lamerie was not a churchgoer. He wasn't interested in attending for the reading of the banns and general obedience marrying in a Huguenot church required. Either that or he was desperate to marry.

From this time on, he is rated for two neighbouring properties in Windmill Street.

In 1718 their first daughter Margaret was born and baptized at St James' Church in Piccadilly, and Anglican church. This proved that Lamerie had little interest in his Huguenot background. To them six children were born: Margaret 1718, Mary 1720, Paul 1725, Daniel 1727, Susannah 1729 and Louisa Elizabeth 1730. Only Mary, Susannah and Louisa survived infancy.

On 18 July 1717 he joined to the Livery Company. The Livery is the first stage of the upper hierarchy of the Goldsimiths' Company.

In 1719 it was the first important piece of work that a large wine-cistern hallmarked for 1719 commissioned by 1st Duke of Sutherland was made.

Walpole Salver by Paul de Lamerie and engraved by William Hogath, 1727. The Vistoria & Albert Museum.It was also at this time, about 1720, that De Lamerie met and started working with William Hogarth (1697-1764), who was possibly the finest engraver of the 18th century. The 'Hogarthian' style of engraving had a huge impact on the pieces designed and made by, not just Paul de Lamerie, but most other silversmiths from this period.

Walpole Salver by Paul de Lamerie and engraved by William Hogath, 1727. The Vistoria & Albert Museum.It was also at this time, about 1720, that De Lamerie met and started working with William Hogarth (1697-1764), who was possibly the finest engraver of the 18th century. The 'Hogarthian' style of engraving had a huge impact on the pieces designed and made by, not just Paul de Lamerie, but most other silversmiths from this period.

On 1 June 1720 a new tax of sixpence an ounce was levied on all new plate, as a result of this new tax, a number of working Goldsmith's including Paul de Lamerie, adopted the practice of removing hallmarks from smaller objects, and incorporating them into heavier and more important pieces, thus avoiding both necessity of submitting them to be assayed or "touched" and the payment of duty became known as "Duty – Dodgers". Some two hundred years later the suspisions of the London Assay Office were aroused concerning the legality of an important basin and ewer made by de Lamerie was heated, a circle of Silver containing the hallmarks dropped out.

In August 1726, officials from Goldsmiths' Hall tried to seize the cargo ship near Customes House, which was of Robert Dingley, a City-based goldsmith and jeweller, who had connections to the Russian court. The large cargo loaded huge amount of ordered silverware for the smuggling trades avoiding the Assay duty. However Paul de Lamerie was a step ahead of them. He had probably been tipped off by someone at the Hall. Dingley was waiting for the officials and took them to the Vine Tavern in Thames Street to discuss the matter, as the ship was moored nearby. As soon as they were inside, the ship sailed for Russia and Goldsmiths' Hall were thwarted. Dingley was brought before Guildhall court, where he testified that the 18,000 ozs of the Czarina's plate were all properly hallmarked. (Today we can check that most of the Czarina's silver collection in Hermitage Museum are not hallmarked and more than half of them bears only the maker's mark of Paul de Lamerie.) This fact was described in the court records.

In 1731, he was made Assistant to the court, the governing body of the Goldsmiths' Company, 'on condition that he paid a fine of forty pounds cash to the use of the company'...'

In 1732, he decided to abandon the Britannia standard for his products, which he had continued to work for apealing his products' superior fineness long after it had ceased to be a legal requirement in 1720.

Commissions came from Royalty and all the wealthiest European families, including Sir Robert Walpole, called "the first British Prime Minister" (1721-42), for whom he made first the square salver, engraved with the Second Exchequer Seal of George I.. Also a remarkable number of Members of Parliament figure among Lamerie's customers. All his most elaborate pieces date from this period.

In the early 1730's he was amongst the first to introduce the Rococo style to the English Aristocrats comes from the French word "rocaille" - the rock and broken shell motifs, which formed part of Rococo design, incorporating elaborate and fantastical decoration, and asymmetry.

On 17 March 1733, he registered his Second Sterling Mark as largeworker. Address: Golden Ball, Windmill Street, St. James's. He was still in Windmill Street, but now at the sign of 'The Golden Ball', the location associated with him thereafter.

From 1736 styled 'Captain'. From 1743 'Majpr', presumably as officer in one of the volunteer associations.

Maynard Dish by Maynard Master working for Paul de Lamerie, 1736/37. Victoria & Albert Museum.In the mid-1730s a gifted artist began to work for Paul de Lamerie. His identity remains obscure, but his hand is distinctive. His outstanding skill first appears on the Maynard dish, marked in 1736/37, leading some to refer to him as the "Maynard Master". He worked for Paul de Lamerie until around 1745. Who was the Maynard Master? There are two candidates. One of them is Chales Frederick Kandler who was trained at Meissen factory in Dresden, and the other is the talented James Shruder (active 1737–1749). Both of them were German origin immigrants, highly skilled modelors and trained in Germany.

Paul de Lamerie, whilst possessing all the skills to make silverware, was unlikely to have made silverware by himself so after his apprenticeship ended. He was primarily a business man organizing Huguenots community including silversmiths and wealthy customers, by using the duty-dodging, by inventing new design and various measures. Paul Crespin (1694-1770), Huguenot silversmith, is thought to have physically manufactured a great deal of silver bearing the maker's mark of Paul de Lamerie around 1720s.

Like Platel, he only took four apprentices, and one of them, Peter Archambo never even trained with him; it was done as a favour to Archambo's father.

In 1733 he started investing in property, like a parcel of land in Piccadilly, land in Gloucestershire in the end, and lent money on mortgages within the French community.

In 1735, His father, Paul Souchay de la Merie, died and was given only a pauper's burial at St Anne's, Soho. Paul moved his mother out of lodgings and in with his family. He joined the Wesminster Militia which was a group concerned with keeping order in the area and he attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel by the time of his death. He did not engage in the militia when his father, a former soldier, was alive.

With his father dead, Paul de Lamerie took more pride in his heritage, and even had Hogarth engrave a bookplate for him showing the Souchay crest (see the three stumps in the centre of the image). Bookplates indicate he was acquiring a library, fitting for the gentleman he had become. His status at the Goldsmiths' Company had changed from grudging acceptance to esteem because of his financial contribution to them.

In December 1737 he was appointed to a Parliamentary Committee of the Goldsmith' Company to prepare a bill 'to prevent the great frauds daily committed in the manufacturing of gold and silver wares for want of sufficient power effectually to prevent the same'. This was the same year that Lamerie sold a massive duty-dodging ewer to Lord Hardwicke. Unsurprisingly, he insisted the clause be 'entirely left out of the new intended bill'. This was agreed at the second meeting and the act was passed in 1738 with his signature attached.

In 1738 He moved to Gerreard Street. Heal records him here at No. 45 to 1739, No. 55 in 1742, and No. 42 from 1743-51, presumably due to directory or rate-book errors.

On 27 June 1739 he registered his third mark. Address: 'Garard' Street. His status in the Goldsmith' Company continued to escalte to fourth Warden in 1743, third Warden in 1746, second Warden in 1747, but never prime Warden, possibly from his failing health.

In 1741 his mother died and buried at St Anne's Church, Soho.

On 29 March 1750 his second surviving daughter Susannah married to Joseph Defaubre.

On 1 August 1751 Paul de Lamerie died and buried at St. Anne's Soho.

In 1751 James Shruder witnessed the signing of Paul de Lamerie's will. His will, dated 24 May 1750, ordered all plate in hand to be finished and stock to be auctioned by Abraham Langford (1711-1774) of Covent Garden, his journeymen Frederick Knopfell and Samuel Collins to have GBP 15 and GBP 20 respectively, the latter "to live with my executors until my Plate in hand shall be finished".

The will contained provisions for the future of his widow and two unmarried daughters out of rents received from two dwelling houses in Gerrard street, Soho, and his two leasehold houses in Haymarket.

The Will also mentions that his book keeper Isaac Gayles, for his long and faithfull services, bequeathed forty guineas. As executors he appointed his wife, and two Hugenot friends, Charles Fouace and John Malliet, to each of whom left 10 guineas for a ring or what else they please.

The short obituary from the London General Evening Post, Thursday August 1 - Saturday August 3, 1751 is worthy of recall: "Last Thursday died Mr Paul de Lamerie of Gerrard Street much regretted by his Family and Acquaintance as a Tender Father, a kind Master and and upright Dealer".

On 11 November 1754 One of the remaining daughters, Mary married John Malliett at St. Anne's.

On 22 September 1761Louisa died unmarried.

On 8 June 1765 Lamerie's widow Louisa died.

Full acknowledgement is made for the above biographical detail to the first and unsurpassable monograph on an English goldsmith, 'Paul De Lamerie' by P. A. S. Phillips, 1935, whose enthusiasm and industry in research stands as a model for every disciple.

Arthur G. Grimwade "London Goldsmiths 1697-1837 Their marks & Lives" and some comments added by Seiji Yamauchi

Development of the Craft

<Phase1> His own products until 1736

By the time that George II ascended the throne in 1727 the entry foreigners into the craft had, except for odd isolated cases, virtually ceased and a second generation of Huguenot craftmen was already working after apprenticeship to their fathers or other compatriots. Paul de Lamerie himself was one of these, having emerged from his articles to Platel in 1712 and by the third decade being firmly established in the leading position, as witness;

- the Sutherland wine-cistern of 1719,

- the scintillating Treby toilet service of 1724,

- the Russian wine-cistern of 1726.

- In 1728 Sir Robert Walpole went to him as the inevitable artist for his Great Seal Salver.

- In 1734 he was called on to produce his two great Chandeliers in the Kremlin, which it is difficult to believe were not direct orders from the Tsarina Anne, since there seems no reason to think that the Imperial crowns and armorials which crown them are from any hand but Lamerie's.

Arthur G. Grimwade "Rococo Silver 1727-1765"

<Phase2> Maynard Master established the most glorious period from 1736 1745.

In 1736 "Maynard Master" started to work for Paul de Lamerie. It was he, whose identity is still a mystery, that established the most glorious period of Rococo during 1736 to 1745. He is known as the Maynard Master, named after the dish made for Grey, 5th Baron Maynard now in the Cahn family collection. Other masterpieces marked by de Lamerie are from the collection of Sir Arthur Gilbert.

<Phase3> His late years from 1745 to 1751

Sutherland Wine Cisren by Paul de Lamerie in 1719

Sutherland Wine Cistern by Paul de Lamerie, 1719. 45.72 x 96.52 x 63.5 cm. The Minneapolice Institute of Arts.Paul de Lamerie registered his first mark in 1712, only seven years before the creation of this masterpiece.

Sutherland Wine Cistern by Paul de Lamerie, 1719. 45.72 x 96.52 x 63.5 cm. The Minneapolice Institute of Arts.Paul de Lamerie registered his first mark in 1712, only seven years before the creation of this masterpiece.

This is the earliest known example of his highly decorative style, showing exceptional imagination and unexpected power in both form and ornament. Similar pieces in the French taste had been made by other goldsmiths before him, but at the time de Lamerie created this cistern, work of this importance and scale was virtually unknown.

Bold, faun-like masks spring from the body to support the vigorous leaf rim. Moulded panels on a Régence scale-pattern ground enclose grotesque marks, and scrolls and shells are chased on the base. The superbly proportioned vessel is given power and individuality by two eccentrically-shaped handles bearing animals' masks on the upper volutes. The sum of the parts demonstrates Paul de Lamerie's ability to produce, even in the early years of his career, a massive piece of highest quality. During large banquets and parties, cisterns were used to chill wine bottles in cool water.

This cistern was made for John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower (1694-1754), in 1719. His grandson, George Granville (1758-1833), was made 1st Duke of Sutherland in 1833. The cistern remained in the family from 1719 to 1961 when it was acquired by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

.

The Minneapolice Institute of Arts

Sutherland Wine Cisren by Paul de Lamerie in 1719

Tureen, by Paul de Lamerie, 1722. The Victoria & Albert Museum.Huguenot goldsmiths first introduced the tureen to England. Those by Paul de Lamerie (1688-1751) are among the earliest known examples made in London. This tureen, along with its pair, belonged to the Edgcumbe family of Mount Edgcumbe, outside Plymouth.

Tureen, by Paul de Lamerie, 1722. The Victoria & Albert Museum.Huguenot goldsmiths first introduced the tureen to England. Those by Paul de Lamerie (1688-1751) are among the earliest known examples made in London. This tureen, along with its pair, belonged to the Edgcumbe family of Mount Edgcumbe, outside Plymouth.

A pair of tureen was remodelled in the 1740s in the fashionable Rococo style. The liners were made by Wakelin and Garrard 1795-1796.

When the Catholic King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, Huguenots (French Protestants) were forced to leave the country. Many were craftsmen who settled in London. Their technical skills and fashionable French style ensured the luxury silver, furniture, watches and jewellery they made were highly sought after. Huguenot specialists transformed English silver by introducing higher standards of craftsmanship. They promoted new forms, such as the soup tureen and sauceboat, and introduced a new repertoire of ornament, with cast sculptural details and exquisite engraving.

Sir Arthur Gilbert and his wife Rosalinde formed one of the world's great decorative art collections, including silver, mosaics, enamelled portrait miniatures and gold boxes. Arthur Gilbert donated his extraordinary collection to Britain in 1996.

The Victoria & Albert Museum

Chesterfield Wine Cooler by Paul de Lamerie in 1727

Chesterfield Wine Cooler, Mark of Paul Crespin overstriking Paul de Lamerie, 1727-8. Victoria & Albert Museum.The Chesterfield Wine Cooler, Mark of Paul Crespin overstriking Paul de Lamerie, 1727-8.

Chesterfield Wine Cooler, Mark of Paul Crespin overstriking Paul de Lamerie, 1727-8. Victoria & Albert Museum.The Chesterfield Wine Cooler, Mark of Paul Crespin overstriking Paul de Lamerie, 1727-8.

'Ice-Pailes', designed to hold a single bottle of wine and prominently displayed in a dining room, were a novelty introduced to England from the court of Louis XIV around 1700. The Jewel House of George II supplied this costly example (one of a pair, the other now in the Royal Museum of Scotland) as part of the ambassadorial silver for Phillip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield when he was appointed English ambassador to The Hague in 1728. When he arrived he added a 50-foot dining room to the ambassadorial residence for entertaining.

Chesterfield was a great connoisseur and enthusiast for French culture and the design of this cooler was based on Paris-made silver of 1710-20. The cast dolphin handles and the four panels chased with the Elements (Fire, Air, Earth and Water) are found on drawings of silver made for the French court. Perhaps Crespin, known for the French character of his silver, supplied the pair to Paul de Lamerie as a subcontractor.

The Jewel House held some second-hand French silver, used as models by the London suppliers. Chesterfield's issue also included candlesticks made by Elie Pacot of Lille as well as exact copies with Paul Crespin's mark.

The Victoria & Albert Museum

Walpole Salver by Paul de Lamerie in 1727

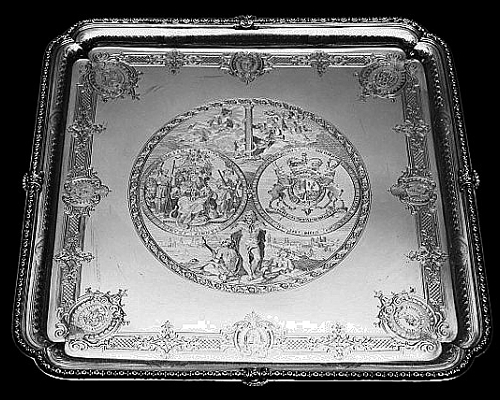

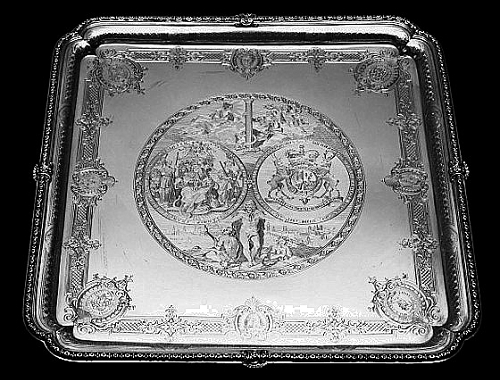

Walpole Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1727. The Vistoria & Albert Museum.This square tray or 'salver' is one of two commissioned by Sir Robert Walpole to commemorate his terms as Chancellor of the Exchequer. It was a long established custom for the holders of certain Crown offices to receive as a perquisite ('perk') the official silver seal of their office when it became redundant, as, for example, after the death of a sovereign. The recipient then commissioned a piece, made from the melted down silver, and had it engraved with the designs of the official seals. Sir Robert Walpole was Chancellor of the Exchequer when George I died in 1727 and this salver is engraved with the design of the Second Exchequer Seal of George I. The salver was eventually inherited by Sir Robert's youngest son, Horace, politician, writer and architectural innovator.

Walpole Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1727. The Vistoria & Albert Museum.This square tray or 'salver' is one of two commissioned by Sir Robert Walpole to commemorate his terms as Chancellor of the Exchequer. It was a long established custom for the holders of certain Crown offices to receive as a perquisite ('perk') the official silver seal of their office when it became redundant, as, for example, after the death of a sovereign. The recipient then commissioned a piece, made from the melted down silver, and had it engraved with the designs of the official seals. Sir Robert Walpole was Chancellor of the Exchequer when George I died in 1727 and this salver is engraved with the design of the Second Exchequer Seal of George I. The salver was eventually inherited by Sir Robert's youngest son, Horace, politician, writer and architectural innovator.

The superb engraving, of the highest quality, is attributed to William Hogarth. The seal roundels are supported by a figure of Hercules, representing Heroic Virtue, flanked by allegorical figures representing Calumny and Envy, with a view of the City of London in the background. The figures above represent Prudence and Fortitude. The border is of elaborate strapwork between masks representing the Four Seasons and cartouches in each corner. These show, within the Garter collar, the double cipher (initials intertwined) 'RW' twice; the arms of Walpole quartering those of his wife Catherine Shorter; and the Walpole crest of a Saracen's head.

The Victoria & Albert Museum

Tea Equipage by Paul de Lamerie in 1735

Tea Equipage by the great goldsmith Paul de Lamerie is illustrated (by kind permission of Leeds Museums and Galleries - Temple Newsam House). It dates to 1735 and has a set of 12 cast whiplash teaspoons, a mote spoon, an unusual pair of tea tongs, a set of twelve tea knives, two tea caddies, a sugar caddy and a milk jug; all these are housed in an elegant, silver mounted, fitted shagreen box. The maker of the tea tongs is John Allen I - a fairly prolific early maker - and it is interesting to note that Paul de Lamerie saw fit to buy in those tongs rather than have tem produced in his workshop. This seems to have been by no means unusual, as other such examples have been recorded. Source: Dr. David Shlosberg, "Eighteenth Century Silver Tea Tongs"This equipage, the earliest complete English tea set preserved, was made as a wedding present for the Huguenors Jean Daniel Boissier and Suzanne Judith Berchere who were married at St. Peter le Poor, London, in April, 1735, and later purchased Lime Grove, Putney. The bride's father, Jaques Louis Berchere, from Paris, a jeweler and banker in Broad Street and an officer of the French church, Threadneedle Street, was probably responsible for the commission. Jean Daniel was the son of Guillaume Boissier, admitted as a Burgess of Geneva in 1695.

Tea Equipage by the great goldsmith Paul de Lamerie is illustrated (by kind permission of Leeds Museums and Galleries - Temple Newsam House). It dates to 1735 and has a set of 12 cast whiplash teaspoons, a mote spoon, an unusual pair of tea tongs, a set of twelve tea knives, two tea caddies, a sugar caddy and a milk jug; all these are housed in an elegant, silver mounted, fitted shagreen box. The maker of the tea tongs is John Allen I - a fairly prolific early maker - and it is interesting to note that Paul de Lamerie saw fit to buy in those tongs rather than have tem produced in his workshop. This seems to have been by no means unusual, as other such examples have been recorded. Source: Dr. David Shlosberg, "Eighteenth Century Silver Tea Tongs"This equipage, the earliest complete English tea set preserved, was made as a wedding present for the Huguenors Jean Daniel Boissier and Suzanne Judith Berchere who were married at St. Peter le Poor, London, in April, 1735, and later purchased Lime Grove, Putney. The bride's father, Jaques Louis Berchere, from Paris, a jeweler and banker in Broad Street and an officer of the French church, Threadneedle Street, was probably responsible for the commission. Jean Daniel was the son of Guillaume Boissier, admitted as a Burgess of Geneva in 1695.

The three canisters and cream jug bear the London hallmarks for 1735-6, and were specially made for the set. The other items were not hallmarked. The canisters are engraved with initials G., B. and S. for Green tea, Bohea tea and sugar respectively. With the exception of the strainer spoon and sugar nippers, every peace, including silver mounts on the original velvet-lined mahogany case, is engraved with the arms of Boissier impaling Berchere. The intervinted handles of the 12 spoons, the elaborate scroll handle of the cream boat, and the chased, cast and engraved ornament on the canisters are early examples of the Rococo style in English silver, of which Paul de Lamerie was the leading exponent. The knives (used to cut the cane-sugar) and the sugar nippers were supplied by a specialist John Allen, who registered his mark as a smallworker at Goldsmiths' Hall in May, 1733.

"The Quiet Conquest - The Huguenots 1685 to 1985", The museum of London

Cup and Cover by Paul de Lamerie, 1736

Cup and Cover by Paul de Lamerie, 1736. Victoria & Albert Museum.In the 18th century the two-handled cup developed into a ceremonial object, rather than a functional one. Covered cups were the ideal grand gift, and became a popular choice of prize for sports. In particular, they were presented to and used by male societies, such as colleges or trade and craft associations. As a result of their status as heirlooms, a disproportionately large number of cups has survived, compared to other categories of silver plate.

Cup and Cover by Paul de Lamerie, 1736. Victoria & Albert Museum.In the 18th century the two-handled cup developed into a ceremonial object, rather than a functional one. Covered cups were the ideal grand gift, and became a popular choice of prize for sports. In particular, they were presented to and used by male societies, such as colleges or trade and craft associations. As a result of their status as heirlooms, a disproportionately large number of cups has survived, compared to other categories of silver plate.

Here, the inverted bell shape is typical of cups of 1720s-80s. The elaborate cast mouldings reveal how de Lamerie, like many London goldsmiths, was moving away from the simpler decoration favoured by earlier generations to the much more ornate Rococo style which became popular in London during the 1730s. 'Rococo' comes from the French word 'rocaille' - the rock and broken shell motifs which formed part of Rococo design.

.

Victoria & Albert Museum

Greatest Objects made by Maynard Master (active 1736-1745)

Maynard Master

The Maynard dish by Paul de Lamerie, London, 1736In the mid-1730s a gifted artist began to work for Paul de Lamerie. His identity remains obscure, but his hand is distinctive. His outstanding skill first appears on the Maynard dish, marked in 1736/37, leading some to refer to him as the "Maynard Master".

The extraordinary border, with figures representing Earth, Air, Fire, and Water, is the first appearance of the artistic personality who executed some of de Lamerie's most ambitious commissions. He is known as the "Maynard Master," after this dish. Probably trained as a chaser, he would have modelled the original plaques in copper, from which moulds were taken to create the silver casts.

There are several distingish quirks of the Maynard Master's style. His compositions are sophisticated, weaving earthy, abstract imagery and naturalism around figural scenes. He favoured low-relief scenes enclosed in an irregular frame, with the field often apparently torn open from the smooth surrounding surface. Exquisitely rendered garlands of flowers or cascades of coral and shells often surround the frame, which might be garnished with distinctive puffy "cinnamon bun" scrolls. The scenes within these elaborate frames are often inhabited scowling, jowly toddlers with large heads and elongated torsos and dimply limbs. His adult figures have long torsos and narrow shoulders. He was particulaly at home in the rendering of turbulent waves or puffy cloudsm sometimes pierced by rays of light or lightning. These might be given a luminous, even liquid quality by delicate chasing and burnishing. Several of the Maynard Master's motifs are common enough that they might be called signatures: an animated droopu lion's head, often resting on its paws, and the head of the infant Mercury, with wings poking through a perkpie hat.

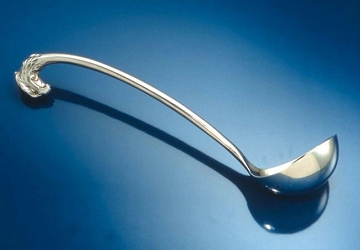

Paul de Lamerie seems to have engaged the Maynard Master for many - though not all - of major commissions from about 1736 to about 1745. A series of ewers and dishes, indluding one made for Goldsmith's Company in 1741/42 and another for the 6th Earl of Mountrath in 1742/43 represent the full range of his capabilities.

Ilchester Ewer and Basin, unmarked, about 1740. Victoria & Albert Museum.Scholars have debated the attribution of an unmarked set known as the Ilchester ewer and dish (shown in the corner below), but although the construction of the ewer is unusual, the set seems to fit comfortably within the Maynard Master's oeuvre.

Ilchester Ewer and Basin, unmarked, about 1740. Victoria & Albert Museum.Scholars have debated the attribution of an unmarked set known as the Ilchester ewer and dish (shown in the corner below), but although the construction of the ewer is unusual, the set seems to fit comfortably within the Maynard Master's oeuvre.

He was not assigned to produce flat relief-decorated objects, though this would seem to have been his specialty. A small group of more sculptural work, indluding the candlesticks in the Cahn collection, and the Marlborough inkstand, represents his efforts in three dimensions.

Ubaldo Vitali, in a recently published paper, suggests that this individual was mainly a chaser who would have worked the models for the cast components of these low-relief borders in metal, a medium with which he was at ease. Some elements of a design might call for wax or wood models, and the cast components might be applied to a chased body, but it is in the chased areas of the low relief that the delicate, flowing character of his scenes is most palpable.

We do not know the nature of the Maynard Master's employment under Paul de Lamerie. Although most of his work bears Paul de Lamerie's mark, he seems to have supplied some finished goods for sale by other goldsmiths. A pair of

small dishes marked by Christian Hillan, for example, have the familiar liminous treatment of clouds and sky and is surely his work, and another example of the same model marked by Peter Archambo is likely to be by his hand as well.

Ellenor Alcorn, "Beyond the Maker's Mark, Paul de Lamerie Silver in the Cahn Collection"

Who was he ? - possible candidate Charles Frederick Kandler but 3 silversmiths used this name

Recently five drawings of design for silver toilet service as wedding gifts requested by the Augstus III, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony (1696-1763), in 1747 are discovered in the Dresden archives by Maureen Cassidy-Geiger. These drawings are attributed to the Maynard Master who worker for Paul de Lamerie from 1736-47.

The Dresden drawings show a kinship with some silver marked by Charles Frederick Kandler who arrived in London from his native Dresden in 1727.

Paul de Lamerie and Charles Frederick Kandler certainly did business together; a group of candlesticks in the Ashmolean Museum, some marked by de Lamerie, and some marked by Kandler, are testimony to that. He is believed to be a youger brother of

Johann Joachim Kaendler, the most famous modellor at Meissen Porcelain Manufacture. Johann lived in London around mid 1730s, probably very short period, and he had premises at Jermyn Street which Chales took over later.

There were possibly 3 silversmiths using the name "Charles Frederick Kandler" in the same peirod.

Design for a mirror, attributed to Maynard Master, circa 1735-47. Seachsisches Staatsarchiv - Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden.

Design for a mirror, attributed to Maynard Master, circa 1735-47. Seachsisches Staatsarchiv - Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden. Mirror by Charles Frederick Kandler, 1741/42. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Mirror by Charles Frederick Kandler, 1741/42. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Ilchester Ewer and Basin, unmarked, about 1740

Ilchester Ewer and Basin, unmarked, about 1740.Ewers and basins, used for washing hands at table in days before forks were in regular use, were the most ambitious form of Elizabethan table plate and continued to be made through the 17th and 18th century for personal and display use. These two beautiful and complex pieces are vigorously sculptural and boldly asymmetrical. Although their designer and maker is not known, their style and use of heraldry strongly suggest that they were made by de Lamerie.

Ilchester Ewer and Basin, unmarked, about 1740.Ewers and basins, used for washing hands at table in days before forks were in regular use, were the most ambitious form of Elizabethan table plate and continued to be made through the 17th and 18th century for personal and display use. These two beautiful and complex pieces are vigorously sculptural and boldly asymmetrical. Although their designer and maker is not known, their style and use of heraldry strongly suggest that they were made by de Lamerie.

An example of the best Rococo design, the helmet-shaped ewer has cast and applied foliage ornament. This is decorated with bullrushes, perhaps from the work of Jean-Baptiste De Lens of Paris who produced a pair of wine coolers in 1732 with very similar decoration. Two asymetrical cartouches (enclosures) flank the handle, which is a mermaid with long flowing hair supporting the body of the ewer with her left arm.

The ewer and basin was probably a love gift from Stephen Fox, created 1st Earl of Ilchester (1741), to his young bride, Elizabeth Strangways Horner, on her 18th birthday. His and her impaled (divided half-and-half) coats of arms are engraved on cartouches on both ewer and basin.

Victoria & Albert Museum

Exhibition at Victoria & Albert Museum

In 2009 the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Galleries at the Victoria & Albert Museum opened. This event was celebrated by the special exhibition "An 18th Century Enigma: Paul de Lamerie and the Maynard Master" held at Room 66 from 11 May 2009 - May 2010.

The silver collection shown at Victoria & Albert Museum is associated with Paul de Lamerie's most brilliant craftsman, whose identity is still a mystery, who worked from 1737 to 1745. He is known as the Maynard Master, named after the dish made for Grey, 5th Baron Maynard now in the Cahn family collection. Other masterpieces marked by de Lamerie are from the collection of Sir Arthur Gilbert.

James Shruder (active 1737-1749)

Another possible candidate of the Maynard Master is the brilliantly talented modeller James Shruder. In 1751 Shruder witnessed the signing of Paul de Lamerie's will, so the two are presumed to have had a deep personal relationship.

Tea Kettle, Stand and Lamp by James Shruder, 1749/50. H: 41.9cm x 29.2cm x 20.9cm. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Tea Kettle, Stand and Lamp by James Shruder, 1749/50. H: 41.9cm x 29.2cm x 20.9cm. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Coffee Pot, 1749/50. H: 28.3cm x 26.0cm. Victoria & Albert Museum.

Coffee Pot, 1749/50. H: 28.3cm x 26.0cm. Victoria & Albert Museum.

His tea-kettle and coffee pot above made as a set by Shruder clearly show the same kind of characteristics of the Maynard Master. Much of the decoration is taken from ornamental engravings by the celebrated French designer Jacques de Lajoue (1686-1761). The sea-horse is from his Second livre de cartouches, published in Paris in 1734, while the dolphins and boat are based closely on a design from the Recueil nouveau de differens cartouches, also of 1734. The sea-horse motif that appears on both the coffee pot and the tea kettle also forms part of the decoration of the enamelled porcelain service made in China for Leake Okeover (1701-1765) around 1740. The goldsmith who made this pot, James Shruder (active 1737-49), unusually designed his own trade card, and he was probably responsible for the scene depicting Poseidon with his trident.

A set of four Candlesticks by James Shruder, 1743. Each baluster form on shaped square base and on four shell, foliate scroll and cartouche bracket feet, cast and chased overall with foliage, rocaille, shells, grotesque masks and vacant cartouches, the vase-shaped socket partly-fluted with rocaille fluting and moulded rim, the detachable nozzle asymmetrical with rocaille texture to the underside, each marked on base and nozzle. The pattern for these candlesticks is ultimately derived from Juste-Aurele Meissonnier, Livre de Chandeliers de Sculpture en Argent, engraved by Huquier, circa 1737. Sold at GBP 117,250 in June 2003, Christie's. Works bearing his mark is fairly rare, and it is often distinguished by sinuous chasing skillfully mingled with finely cast applied details. The set of tea canisters and sugar bowl of 1748/49 in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is characteristic. A tea-kettle, coffee pot, and hot water urn of 1749/50 are fully realized rococo confections, showing the designer's reliance on engraved desings by Jacques de Lajoue (1686-1761). It has been suggested that Shruder may have been one of Paul de Lamerie's gifted "behind the scenes" modeler/chaser (Clifford, "Lamerie", pp. 24-25).

A set of four Candlesticks by James Shruder, 1743. Each baluster form on shaped square base and on four shell, foliate scroll and cartouche bracket feet, cast and chased overall with foliage, rocaille, shells, grotesque masks and vacant cartouches, the vase-shaped socket partly-fluted with rocaille fluting and moulded rim, the detachable nozzle asymmetrical with rocaille texture to the underside, each marked on base and nozzle. The pattern for these candlesticks is ultimately derived from Juste-Aurele Meissonnier, Livre de Chandeliers de Sculpture en Argent, engraved by Huquier, circa 1737. Sold at GBP 117,250 in June 2003, Christie's. Works bearing his mark is fairly rare, and it is often distinguished by sinuous chasing skillfully mingled with finely cast applied details. The set of tea canisters and sugar bowl of 1748/49 in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is characteristic. A tea-kettle, coffee pot, and hot water urn of 1749/50 are fully realized rococo confections, showing the designer's reliance on engraved desings by Jacques de Lajoue (1686-1761). It has been suggested that Shruder may have been one of Paul de Lamerie's gifted "behind the scenes" modeler/chaser (Clifford, "Lamerie", pp. 24-25).

He certainly had business contacts with Paul de Lamerie: the set of forks and spoons in the Cahn collection bear Paul de Lamerie's mark overstruck by Shruder's.

Ellenor Alcorn, the author of "Beyond the Maker's Mark, Paul de Lamerie Silver in the Cahn Collecton" commented that "However there is little stylistic relationship between the elaborately chased work bearing Shruder's mark and that bearing Paul de Lamerie's, so it is unlikely that Shruder was personally responsible for Paul de Lamerie's ambitious rococo creation." However this judgement is highly doubtful given the wider variety of styles Shruder could accomodated.

He would be a German Catholic immigrant however there was no records of apprenticeship or freedom. He had distingushed modelling techniques and undoubtedly the finest metal chaser and a gilder at his time.

James Shruder entered his first mark as largeworker on 1 August 1737. Address: Wardour Street, St. Ann's, Westminster. Second and third marks were registered on 25 June 1739. Address: Greek Street, Soho.

He was bankrupt in June 1749 as Goldsmith, St. Martin's in the Fields (The Gentleman's Magazine, p. 285).

Heal records him as 'James Shruder at the Golden Ewer in Spur Street, Leicester Square' with the addition of the sign of the Golden Ewer in Greek Street; as well as Corner of Hedge Lane, Leicester Square, from 1744.

The charcter of his work, at its best some of the finest Rococo plate of the day, suggests a German origin and training to match his name. His power as a designer is exemplified by his highly origin tradecard (Heal, plate LXV) signed 'J. Shruder Inv.' and engraved by J. Warburton.

Many highly skilled silversmiths of the period failed in their business ventures. Shruder seems to have struggled as a retailer. He declared bankruptcy in 1749.

In 1763 he is listed as a "Modeller and Papier Mache Manufacturer" in Mortimer's Universal Director. He may have continued to work as a chaser, supplying other retailers with finished goods for marketing, or worked on a small scale, marking wares with an unregistered punch.

Sources: Arthur G. Grimwade, "London Goldsmiths 1697-1837 Their Marks & Lives" and Ellenor Alcorn, the author of "Beyond the Maker's Mark, Paul de Lamerie Silver in the Cahn Collecton"

Four salts by Paul de Lamerie in 1739/40

Set of Four Salts and Spoons by Paul de Lamerie, London, 1739. These salts were acquired by Clark with two identical copies supplied by a victorian silversmith Paul Storr in 1819A set of four cast salts with accompanying spoons illustrates the marriage of naturalism and fantasy so characteristic of the rococo style. Each salt is conceived as a abalone shell supported by a mermaid draped in netting, encrusted with sea shells and coral. Sea shell and coral spoons continue the marine theme. The four salts, marked by de Lamerie in 1739/40, were acquired by Clark in 1930 with two identical copies by Paul Storr (1771-1844) dated 1819/20. Storr borrowed freely from de Lamerie's work and is known to have supplemented objects originally supplied by the earlier goldsmith. (1)

(1) For examples, see Arthur Grimwade, "Family Silver of Three Centuries," Apollo, vol. 82 (December 1965), p. 500, Fig. 4; and Arthur G. Grimwade, The Queen's Silver, A Survey of Her Majesty's Personal Collection (The Connoisseur, London, 1953), Pl. 17.

Silver in the Clark Art Institute - Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Magazine Antiques, Oct, 1997 by Beth Carver Wees

Newdigate Centrepiece Paul de Lamerie in 1743/44

Newdigate Centrepiece by Paul de Lamerie, 1743. Victoria & Albert Museum.Centrepieces sometimes comprise several separate objects, designed to be seen together along a table, often including functional items such as tureens containing ragouts (spicy stew). By the 1750s, this composite centrepiece had developed into the now more familiar dessert centrepiece, which became the grandest single item of dining silver, often with hanging baskets and placed in the centre of the table for formal meals. As here, some were very elaborate and could serve as a fruit stand, set out at the beginning of the meal and supplemented by further dishes of fruits and sweetmeats for the dessert course. Sweetmeats, long known in the Middle East and Asia and to the ancient Egyptians, were at first preserved or candied fruits, probably made with honey. Subsequently, dessert foods from custards to candied violets were referred to as sweetmeats. Wet varieties were eaten with a spoon and included jellies, creams, floating islands and preserved fruits in heavy syrups. Dry varieties, for which this centrepiece could have been used, included nuts, fruit peels, glacéed fruit, sugared comfits and flowers, chocolates and small cakes.

Newdigate Centrepiece by Paul de Lamerie, 1743. Victoria & Albert Museum.Centrepieces sometimes comprise several separate objects, designed to be seen together along a table, often including functional items such as tureens containing ragouts (spicy stew). By the 1750s, this composite centrepiece had developed into the now more familiar dessert centrepiece, which became the grandest single item of dining silver, often with hanging baskets and placed in the centre of the table for formal meals. As here, some were very elaborate and could serve as a fruit stand, set out at the beginning of the meal and supplemented by further dishes of fruits and sweetmeats for the dessert course. Sweetmeats, long known in the Middle East and Asia and to the ancient Egyptians, were at first preserved or candied fruits, probably made with honey. Subsequently, dessert foods from custards to candied violets were referred to as sweetmeats. Wet varieties were eaten with a spoon and included jellies, creams, floating islands and preserved fruits in heavy syrups. Dry varieties, for which this centrepiece could have been used, included nuts, fruit peels, glacéed fruit, sugared comfits and flowers, chocolates and small cakes.

This elaborate centrepiece, a wedding present, is richly decorated with characteristic Rococo motifs - bold scrollwork, flowers and shells - but also contains elements typical of de Lamerie's work, such as the helmetted putti.

The Victoria & Albert Museum

Wine Cooler by Paul de Lamerie in 1749/50

Wine Cooler by Paul de Lamerie, 1749. Victoria & Albert Museum.The style of this wine cooler, one of a pair, reflects the late use of some familiar motifs from de Lamerie's workshop. However silver marked by de Lamerie in the years before his death in 1751 is not as stylistically cohesive as his earlier work, raising the possibility that he was retailing wares from a broader range of makers.

Wine Cooler by Paul de Lamerie, 1749. Victoria & Albert Museum.The style of this wine cooler, one of a pair, reflects the late use of some familiar motifs from de Lamerie's workshop. However silver marked by de Lamerie in the years before his death in 1751 is not as stylistically cohesive as his earlier work, raising the possibility that he was retailing wares from a broader range of makers.

The Victoria & Albert Museum

Tureen by Paul de Lamerie in 1750

Tureen by Paul de Lamerie, 1750. The Cahn Collection loan to Victoria & Albert Museum.Marked by Paul de Lamerie, 1750/51, On loan from the Cahn Collection

Tureen by Paul de Lamerie, 1750. The Cahn Collection loan to Victoria & Albert Museum.Marked by Paul de Lamerie, 1750/51, On loan from the Cahn Collection

The green turtle was a food staple in the West Indies, but in 1750 it would have been an exotic delicacy in England. The flesh was considered cleansing and, with its eggs, was thought to be an aphrodisiac. Within a decade or two, turtle soup was a standard component of the civic banquet, symbolising magnificence and plenty. This tureen may have been ordered by a prosperous plantation owner or for an English trading company. A coat of arms has apparently been removed from the cover perhaps at the same time the unusual etching was added to define the turtle's shell.

Victoria & Albert Museum

Works of Arts / Paul de Lamerie

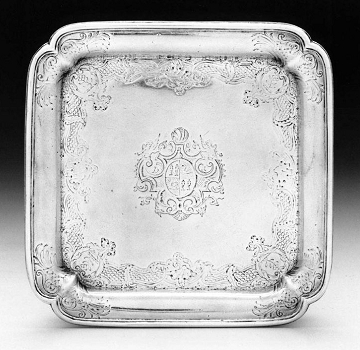

Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1734. 3.2 x 24.4 x 24.4 cm. Blooklyn Museum. Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1734. 3.2 x 24.4 x 24.4 cm. Blooklyn Museum. |  Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1734. 2.2 x 14.6 x 14.5 cm, 343g. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1734. 2.2 x 14.6 x 14.5 cm, 343g. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Sauceboat by Paul de Lamerie, 1735. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Sauceboat by Paul de Lamerie, 1735. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |  Tureen by Paul de Lamerie, 1736. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Tureen by Paul de Lamerie, 1736. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Dish and Ewer made for Goldsmiths' Company, 1741, Paul de Lamerie. Dish and Ewer made for Goldsmiths' Company, 1741, Paul de Lamerie. |

Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1742. Salver by Paul de Lamerie, 1742. |  Loving cup with cover by Paul de Lamerie in 1742-43, London. 38.4 ×24.1cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is one of four identical cup made in the same year. Loving cup with cover by Paul de Lamerie in 1742-43, London. 38.4 ×24.1cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is one of four identical cup made in the same year. |

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me