Japonisme

Fashionable young women inspect a Japanese screen, in a painting by James Tissot, ca 1869-70Japonism, or Japonisme, the original French term, which is also used in English, is a term for the influence of the arts of Japan on those of the West. The word was first used by Jules Claretie in his book L'Art Francais en 1872 published in that year. Works arising from the direct transfer of principles of Japanese art on Western, especially by French artists, are called Japonesque.

Fashionable young women inspect a Japanese screen, in a painting by James Tissot, ca 1869-70Japonism, or Japonisme, the original French term, which is also used in English, is a term for the influence of the arts of Japan on those of the West. The word was first used by Jules Claretie in his book L'Art Francais en 1872 published in that year. Works arising from the direct transfer of principles of Japanese art on Western, especially by French artists, are called Japonesque.

From the 1860s, ukiyo-e, Japanese wood-block prints, became a source of inspiration for many European impressionist painters in France and the rest of the West, and eventually for Art Nouveau and Cubism. Artists were especially affected by the lack of perspective and shadow, the flat areas of strong color, the compositional freedom in placing the subject off-centre, with mostly low diagonal axes to the background.

Although Japanese export artefacts started the fashion for a Japanese style during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Europe, it was little more than a fad for exotic things. Japanese styles were applied purely for decorative effect.

Japonisme, which appeared in the second half of the nineteenth century, is generally differentiated from such earlier Japanese influence in its deeper understanding of the concepts underlying Japanese art. Western pictorial artists had started to use the concept of Japanese art to free themselves from Western classical tradition. Japanese wood block prints, ukiyo-e, were newly introduced to the West in the nineteenth century, and had a sensational impact on Western art. Asymmetrical arrangement, blank backgrounds, flat and linear depiction disregarding mathematical perspective - none of these featured in the traditional canon of which had ruled in the West for centuries. These elements were merged with Western practices and new styles emerged.

Limited information about Japanese art was available to the West before Japanís reopening in 1854. For example, Philippe Franz von Siebold(1796–1866), a German physician, issued one of the first thorough studies of Japan, Archiv zur Bescheibung von Japan in 1831, which was also published in France in 1838. Additionally, he brought copies of Hokusai Manga back to Holland in 1830 and exhibited them at his museum in Leiden opened to the public in 1837.

Some scholars suggest the link between these ukiyo-e and French Japonisme. It is, however, commonly acknowledged that Japonisme emerged after 1854 when more information on Japanese art became available. A number of books were written by ambassadors who returning from service in Japan. For instance, Laurence Oliphant (1829–1888) published his two-volume Narrative of the Earl of Elginís Mission to China and Japan in 1859, consisting of some Japanese wood block prints. These books were an immediate success and editions in the US and France followed in 1860. In 1863, Sir Rutherford Alcock (1809–1897), the first British diplomatic representative in Japan, published his famous The Capital of the Tycoon, which included numerous prints of superb quality chosen by the author who was a serious collector of Japanese art.

Turning to the availability of Japanese decorative arts in Europe (excluding Holland), a British ship carrying a full load of Japanese crafts returned to London in 1854. These were exhibited at the Old Watercolour Society Gallery in Pall Mall East and became the first opportunity for the British to encounter Japanese crafts. Although this early event did not make any immediately noticeable impact on British art, it was featured by the London Illustrated News on 4 February 1854 with great acclaim. There were lacquered desks with mother-of-pearl and metal inlays, cabinets, boxes, bronze works, porcelains, textiles, prints, amongst other works. Judging from the designs illustrated in the newspaper and the date of the exhibition, the furniture was apparently Nagasaki lacquer. The design of the table with bat-shaped legs in the middle was illustrated in the book called Aogai Maki-e Hinagata Hikae (Lacquered Design Manuals, Nagasaki Aogai) published in Nagasaki in 1856. The Science and Art Department, British government body, made large purchases from these exhibits upon the recommendation of prominent critics.

The International Exhibition in London, 1862, was the first major introduction of Japanese art to the West. Sir Rutherford Alcock, who returned from diplomatic service in Japan, displayed his comprehensive Japanese collection including over 600 paintings, prints, textiles, paper samples, porcelain, lacquers, bronze works at the Japanese Court. The whole exhibition was not as huge a commercial success as the Great Exhibition of 1851, but Japanese crafts deeply impressed some intellectuals and artists. One of these was the young Arthur Lasenby Liberty(1843–1917), who urged his employer, Farmer and Rogers, to buy in the unsold exhibits of Japanese crafts. His passion for Japanese art lasted for a long time and Liberty & Co., established in 1875, became the foremost stockist of Japanese crafts in Britain.

Japan participated officially in a world exhibition for the first time in 1867, at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Their exhibits included several thousand items, such as weapons, books, paintings, prints, musical instruments, lacquers, ceramics, metal works, papers, and textiles. This extensive display made a deep impression on Parisian artists, and the mania for things Japanese spread rapidly.

The influence of Japanese art was also strongly felt in the United States, although it was not so intense until the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. This fair achieved tremendous success with a total of 11.65 million visitors, and the Japanese section, displaying an enormous quantity of decorative arts, drew a huge crowd. The Illustrated Catalogue of the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876 stated:

Anything from Japan has always been looked upon with interest, because curiosities are interesting. The Japanese collection in the Main Building received a great deal of attention, and, although there was much to smile at as grotesque and ìoutlandishî, there was very much to delight the eye in the delicate and intricate workmanship . . .

For the first ten years or so after the reopening of Japan, the passion for Japanese art was confined to individual artists and collectors. In the 1870s, when more information and materials became available, the vogue took off in earnest and numerous Japanese style interiors were created. This trend was carried to extremes in the 1880s, particularly in England, and thousands of ordinary homes were filled with Japanese style decorative objects such as fans, umbrellas, and porcelain. British zeal for Japanese fashion was chiefly concentrated in the decorative arts, promoted by the active involvement of major industrial manufacturers, as opposed to other countries where fine arts were the main focus.

History

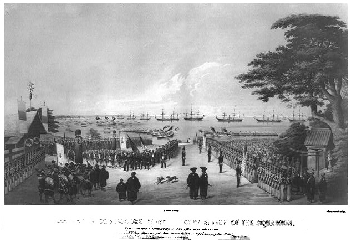

Landing of Commodore Perry, officers & men of the squadron, to meet the Imperial commissioners at Yoku-Hama July 14th 1853. Lithograph by Sarony & Co., 1855, after W. Heine. William (Wilhelm) Heine was the official artist of Commodore Matthew C. Perry's expedition to Japan in 1853-54. On returning to the United States, he produced a several series of 10 prints commemorating the trip. This project employed the New York lithographic firm of Sarony, at that time probably the most skilled craftsmen in their profession in the United States.During the Kaei era (1848 – 1854), foreign merchant ships began to come to Japan. In 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry (1794–1858), sailed into Tokyo Bay and after a show of force, Perry convinced Japanese authorities to sign the Convention of Kanagawa on March 31, 1854. The treaty opened the Japanese ports of Shimoda 下田 and Hakodate 函館 to United States trade and guaranteed the safety of shipwrecked U.S. sailors. The treaty establish a foundation for the Americans to maintain a permanent consul in Shimoda.

Landing of Commodore Perry, officers & men of the squadron, to meet the Imperial commissioners at Yoku-Hama July 14th 1853. Lithograph by Sarony & Co., 1855, after W. Heine. William (Wilhelm) Heine was the official artist of Commodore Matthew C. Perry's expedition to Japan in 1853-54. On returning to the United States, he produced a several series of 10 prints commemorating the trip. This project employed the New York lithographic firm of Sarony, at that time probably the most skilled craftsmen in their profession in the United States.During the Kaei era (1848 – 1854), foreign merchant ships began to come to Japan. In 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry (1794–1858), sailed into Tokyo Bay and after a show of force, Perry convinced Japanese authorities to sign the Convention of Kanagawa on March 31, 1854. The treaty opened the Japanese ports of Shimoda 下田 and Hakodate 函館 to United States trade and guaranteed the safety of shipwrecked U.S. sailors. The treaty establish a foundation for the Americans to maintain a permanent consul in Shimoda.

The pact led to significant commercial trade between the United States and Japan, but it also contributed to opening up Japan to other Western nations. Before 1853, Japan had been applying 200 year policy of seclusion (Sakoku 鎖国). In 1639 under Tokugawa Iemitsu 徳川家光 (1604-1651) officially closed off Japan from the rest of the world, limiting trade to the Dutch merchants ensconced on the island of Dejima in Nagasaki and the proxy trade with China carried out by the Ryukyu Kingdom under the control of the Shimazu clan. It remained in effect until 1853 with the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry and the opening of Japan. It was still illegal to leave Japan until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Following the Meiji restoration, Japan ended a long period of national isolation and became open to imports from the West, including photography and printing techniques; in turn, many Japanese ukiyo-e prints and ceramics, followed in time by Japanese textiles, bronzes and cloisonné enamels and other arts came to Europe and America and soon gained popularity.

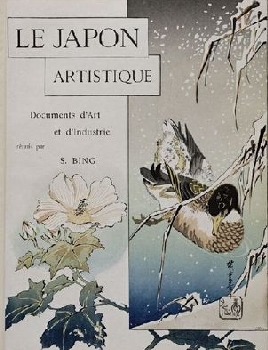

Cover of the French magazine Le Japon artistique (1888) Japonism started with the frenzy to collect Japanese art, particularly print art calles ukiyo-e 浮世絵 of which the first samples were to be seen in Paris. About 1856, the French artist Felix Bracquemond first came across a copy of the sketch book Hokusai Manga at the workshop of his printer; they had been used as packaging for a consignment of porcelain. In 1860 and 1861 reproductions (in black and white) of ukiyo-e were published in books on Japan. Baudelaire wrote in a letter in 1861: "Quite a while ago I received a packet of japonneries. I've split them up among my friends..", and the following year La Porte Chinoise, a shop selling various Japanese goods including prints, opened in the rue de Rivoli, the most fashionable shopping street in Paris.[1] In 1871 Camille Saint-Saëns wrote a one-act opera, La princesse jaune to a libretto by Louis Gallet, in which a Dutch girl is jealous of her artist friend's fixation on an ukiyo-e woodblock print.

Cover of the French magazine Le Japon artistique (1888) Japonism started with the frenzy to collect Japanese art, particularly print art calles ukiyo-e 浮世絵 of which the first samples were to be seen in Paris. About 1856, the French artist Felix Bracquemond first came across a copy of the sketch book Hokusai Manga at the workshop of his printer; they had been used as packaging for a consignment of porcelain. In 1860 and 1861 reproductions (in black and white) of ukiyo-e were published in books on Japan. Baudelaire wrote in a letter in 1861: "Quite a while ago I received a packet of japonneries. I've split them up among my friends..", and the following year La Porte Chinoise, a shop selling various Japanese goods including prints, opened in the rue de Rivoli, the most fashionable shopping street in Paris.[1] In 1871 Camille Saint-Saëns wrote a one-act opera, La princesse jaune to a libretto by Louis Gallet, in which a Dutch girl is jealous of her artist friend's fixation on an ukiyo-e woodblock print.

At first, despite Braquemond's initial contact with one of the classic masterpieces of ukiyo-e, most of the prints reaching the West were by contemporary Japanese artists of the 1860s and 1870s, and it took some time for Western taste to access and appreciate the greater masters of older generations.

At the same time, many American intellectuals maintained that Edo prints were a vulgar art form, unique to the period and distinct from the refined, religious, national heritage of Japan known as Yamato-e 大和絵 (pictures from the Yamato period, e.g. those of Zen masters Sesshū and Shūbun).

Artists and movements

Japanese artists who had a great influence included Utamaro and Hokusai. Curiously, while Japanese art was becoming popular in Europe, at the same time, the "bunmeikaika" 文明開化 (Westernization) led to a loss in prestige for the prints in Japan.

Van Gogh, The Blooming Plum Tree (after Hiroshige), 1887Artists who were influenced by Japanese art include Arthur Wesley Dow, Pierre Bonnard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Renoir, James McNeill Whistler (Rose and silver: La princesse du pays de porcelaine, 1863-64), Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, Bertha Lum, Will Bradley, Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt, the sisters Frances and Margaret Macdonald, as well as architects Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Stanford White. Some artists, such as Georges Ferdinand Bigot, even moved to Japan because of their fascination with Japanese art.

Van Gogh, The Blooming Plum Tree (after Hiroshige), 1887Artists who were influenced by Japanese art include Arthur Wesley Dow, Pierre Bonnard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Renoir, James McNeill Whistler (Rose and silver: La princesse du pays de porcelaine, 1863-64), Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, Bertha Lum, Will Bradley, Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt, the sisters Frances and Margaret Macdonald, as well as architects Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Stanford White. Some artists, such as Georges Ferdinand Bigot, even moved to Japan because of their fascination with Japanese art.

Although works in all media were influenced, printmaking was not surprisingly particularly affected, although lithography, not woodcut, was the most popular medium. The prints and posters of Toulouse-Lautrec can hardly be imagined without the Japanese influence. Not until Félix Vallotton and Paul Gauguin was woodcut itself much used for japonesque works, and then mostly in black and white.

Whistler was important in introducing England to Japanese art. Paris was the acknowledged center of all things Japanese and Whistler acquired a good collection during his years there.

Several of Van Gogh's paintings imitate ukiyo-e in style and in motif. For example, Le Père Tanguy, the portrait of the proprietor of an art supply shop, shows six different ukiyo-e in the background scene. He painted The Courtesan in 1887 after finding an ukiyo-e by Kesai Eisen on the cover of the magazine Paris Illustré in 1886. At this time, in Antwerp, he was already collecting Japanese prints.

Japonism also had an effect on music. In 1885 Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera The Mikado was said to be inspired by the Japanese Native Village exhibition in Knightsbridge, London,[3] although the exhibition did not open until after the opera was already in rehearsal. Sullivan used a version of the song, "Ton-yare Bushi" by Ômura Masujiro in The Mikado. Giacomo Puccini also made use of the same tune in his opera Madama Butterfly in 1904.

There were many characteristics of Japanese art that influenced these artists. In the Japonisme stage, they were more interested in the asymmetry and irregularity of Japanese art. Japanese art consisted of off centered arrangements with no perspective, light with no shadows and vibrant colors on plane surfaces. These elements were in direct contrast to Roman-Greco art and were embraced by 19th century artists, who believed they freed the Western artistic mentality from academic conventions.

Ukiyo-e, with their curved lines, patterned surfaces and contrasting voids, and flatness of their picture-plane, also inspired Art Nouveau. Some line and curve patterns became graphic clichés that were later found in works of artists from all parts of the world. These forms and flat blocks of color were the precursors to abstract art in modernism.

Japonism also involved the adoption of Japanese elements or style across all the applied arts, from furniture, textiles, jewellery to graphic design.

Wikipedia

Japonisme Furniture style

The vogue for Japanese style called for the creation of furniture with Japanese looks, and some started to invent a new kind of furniture based on their interpretation of a Japanese aesthetic. Such furniture divides into two categories: one characterised by straight lines and another by flowing curves.

The former was represented by Edward William Godwin (1833–1886), Christopher Dresser(1834–1904), Thomas Jeckyll (1827–1881) and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) who referred to traditional Japanese furniture and interiors as their design sources. It is known, for example, that Edward William Godwin owned two volumes of Hokusai Manga as early as 1862, from which he learned the techniques of Japanese furniture construction, and in 1867 he designed an extremely innovative cabinet. Christopher Dresser visited Japan in 1876 and made a first hand study of Japanese interiors, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh was strongly influenced by Edward William Godwin. The Peacock Room made for Frederick Leyland by James Abbott McNeil Whistler (1834–1903) and Thomas Jeckyll in 1876 was one of the best known examples.

Furniture with sinuous contours was more commonly found in France and derived from the flowing lines of ukiyo-e. The leading French Art Nouveau designer, Emile Galle (1846–1904), typifies this style.

In addition to such furniture created by prominent designers, numerous items in Japanese style were produced in Europe and sold at Japanese warehouses and department stores. In London, besides Liberty & Co., Whiteley opened an oriental department in 1874, later followed by Debenham & Freebody and Swan & Edgar, Maples, and others.

The fashion for Japan remained popular in the West even after the 1880s, and Japan was a frequent topic amongst artists and intellectuals. For instance, a British leading artistic magazine of the day, The Studio, featured miscellaneous aspects of Japanese art and culture continually throughout the 1890s and 1900s.

Particularly, the edition of July 1899, dedicated eight pages to the Japanese-inspired house of Mortimer Menpes, an Australian painter, with ten photographs. He was apprenticed to James Abbott McNeil Whistler and visited Japan in 1887 to study Japanese art. On his second visit in 1896, he ordered all the interior fittings for his mansion at 25 Cadogan Garden in Chelsea from nearly 100 Japanese craftsmen woodcarvers, metalworkers, painters and lacquerers who worked from precise drawings supplied by Menpes. The carved friezes, ceiling panels, furniture, doors and windows produced under his one-year supervision were packed in 200 cases and shipped to London. It took him another two years to fit these materials into his house. The interior, displaying an excellent marriage of East and West, was highly esteemed and described as ìone of the most remarkable houses in the world and a gorgeous Eastern Palace in Commonplace Chelsea. The rectilinear design of the interior was punctuated with numerous carved wooden panels which resembled those of Japanese temples. Most of the furniture was inspired by traditional Japanese designs, but, strangely, some items such as small tables and chairs of Chinese origin were mixed in, which was criticised by The Studio in the above-mentioned article.

It can be said that the real dialogue between Japan and the West finally started in the Meiji era. This is the reason why Japonisme and the Aesthetic Movement in the West were curiously echoed by the craze for Westernisation in Japan. In the course of these cultural interchanges, much hybrid furniture was produced based on different interpretations of each designer in the West and Japan. Some Westerners seriously searched for the key to the Japanese aesthetic, while others sought only superficial exoticism. Mirroring these activities in the West, hybridisation took place in the area of furniture production in the Meiji era, based on Japanese ideas of how Western furniture should be adapted to Japanese society, and which style Westerners would think of as being Japanese and attractive. This resulted in various kinds of output. In the West, minimalist designs typified by Godwin, elaborate marquetry furniture by Galle, and inexpensive Anglo-Japanese furniture sold at numerous retailers was produced. In Japan, diversified Western furniture with Japanese decoration was created for the home and export markets. Particularly that made for the export market was unique in many ways, as will be examined in detail in the next chapter.

Aestheticism

The Aesthetic Movement is a 19th century European movement that emphasized aesthetic values over moral or social themes in literature, fine art, the decorative arts, and interior design. Generally speaking, it represents the same tendencies that symbolism or decadence stood for in France, or decadentismo stood for in Italy, and may be considered the British branch of the same movement. It belongs to the anti-Victorian reaction and had post-Romantic roots, and as such anticipates modernism. It took place in the late Victorian period from around 1868 to 1901, and is generally considered to have ended with the trial of Oscar Wilde (which occurred in 1895).

Aesthetic Movement literature

The British decadent writers were deeply influenced by the Oxford don Walter Pater and his essays published in 1867–68, in which he stated that life had to be lived intensely, following an ideal of beauty. His Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) became a sacred text for art-centric young men of the Victorian era. Decadent writers used the slogan "Art for Art's Sake" (L'art pour l'art), whose origin is debated. It is generally accepted to have been widely promoted by Théophile Gautier in France, who took the phrase to suggest that there was no connection between art and morality.

The artists and writers of the Aesthetic movement tended to hold that the Arts should provide refined sensuous pleasure, rather than convey moral or sentimental messages. As a consequence, they did not accept John Ruskin and Matthew Arnold's utilitarian conception of art as something moral or useful. Instead, they believed that Art did not have any didactic purpose; it need only be beautiful. The Aesthetes developed the cult of beauty, which they considered the basic factor in art. Life should copy Art, they asserted. They considered nature as crude and lacking in design when compared to art. The main characteristics of the movement were: suggestion rather than statement, sensuality, massive use of symbols, and synaesthetic effects—that is, correspondence between words, colours and music. It was the music that set the mood.

Aestheticism had its forerunners in John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, and among the Pre-Raphaelites. In Britain the best representatives were Oscar Wilde and Algernon Charles Swinburne, both influenced by the French Symbolists, and James McNeill Whistler and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Compton Mackenzie's novel Sinister Street makes use of the type as a phase through which the protagonist passes under the influence of older, decadent individuals. The novels of Evelyn Waugh, who was a young participant in aesthete society at Oxford, portray the aesthete mostly from a satirical point of view, but also from that of an insider. Some names associated with this loose assemblage are Robert Byron, Evelyn Waugh, Harold Acton, Nancy Mitford, A.E. Housman and Anthony Powell.

Aesthetic Movement visual arts

Artists associated with the Aesthetic movement include James McNeill Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, and Aubrey Vincent Beardsley.

Aesthetic Movement decorative arts

Aesthetic furniture was limited to approximately late nineteenth-century. Furniture typically originated in Britain/Ireland (usually referred to as simply "Aesthetic") or in the United States (usually referred to as "American Aesthetic").

Aesthetic movement furniture is characterized by several common themes:

- Ebonized wood with gilt highlights

- Japanese influence

- Prominent use of nature, especially flowers, birds, ginko leaves, and peacock feathers.

- Blue and white on porcelain and china.

An Aesthetic Movement overmantle, showing ebonized wood with gilded highlights of peacock feathers and flowers, and a top which has a color painting of birds and flowers.Ebonized furniture means that the wood is painted or stained to a black ebony finish. The furniture is sometimes completely ebony-colored. More often however, there is gilding added to the carved surfaces of the feathers or stylized flowers that adorn the furniture.

An Aesthetic Movement overmantle, showing ebonized wood with gilded highlights of peacock feathers and flowers, and a top which has a color painting of birds and flowers.Ebonized furniture means that the wood is painted or stained to a black ebony finish. The furniture is sometimes completely ebony-colored. More often however, there is gilding added to the carved surfaces of the feathers or stylized flowers that adorn the furniture.

Trade had just opened with Japan in the 1850s and 1860s. Japanese influences, epitomized by the 1885. Japanese exhibition in Knightsbridge, influenced aesthetic furniture and furnishings. There are commonalities especially in the overall rectangular shape with columns, and the intricate woodcarvings, this influence can be seen in a concurrent movement known as the Anglo-Japanese style, especially in the work of E.W. Godwin and Christopher Dresser.

As aesthetic movement decor was similar to the writing in that it was about sensuality and nature, nature themes often appear on the furniture. A typical aesthetic feature is the gilded carved flower, or the stylized peacock feather. Colored paintings of birds or flowers are often seen. Non-ebonized aesthetic movement furniture may have realistic 3D renditions of birds or flowers carved into the wood.

Contrasting with the ebonized-gilt furniture is use of blue and white in porcelain and china. Similar themes of peacock feathers and nature would be used in blue and white tones on dinnerware and other crockery. The blue and white design was also popular on square porcelain tiles. It is reported that Oscar Wilde used aesthetic decorations during his youth.

In 1882, Oscar Wilde visited Canada where he toured the town of Woodstock, Ontario and gave a lecture on May 29 entitled; "The House Beautiful". This particular lecture featured the early Aesthetic art movement also known as the "Ornamental Aesthetic" art movement, where local flora and fauna were celebrated as beautiful and textured, layered ceilings were popular. A gorgeous example of this can be seen in Annandale National Historic Site, located in Tillsonburg, Ontario, Canada. The house was built in 1880 and decorated by Mary Ann Tillson, who happened to attend Oscar Wilde's lecture in Woodstock, and was inspired. Since the Aesthetic art movement was only prevalent in 1880 through to 1890, there are not very many examples of this particular style left today.

Peacock Room

The Peacock Room, designed by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, one of the most famous examples of Aesthetic movement interior designHarmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room is James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)'s masterpiece of interior decorative mural art. He painted the paneled room in a rich and unified palette of brilliant blue-greens with over-glazing and metallic gold leaf. Painted in 1876-1877, it is now considered a high example of the Anglo-Japanese style.

The Peacock Room, designed by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, one of the most famous examples of Aesthetic movement interior designHarmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room is James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)'s masterpiece of interior decorative mural art. He painted the paneled room in a rich and unified palette of brilliant blue-greens with over-glazing and metallic gold leaf. Painted in 1876-1877, it is now considered a high example of the Anglo-Japanese style.

Unhappy with the first decorative result by another artist, Leyland left the room in Whistler's care to make minor changes, "to harmonize" the room whose primary purpose was to display Leyland's china collection. However, Whistler let his imagination run wild, "Well, you know, I just painted on. I went on—without design or sketch—putting in every touch with such freedom…And the harmony in blue and gold developing, you know, I forgot everything in my joy of it."

Upon returning, Leyland was shocked by the "improvements". Artist and patron quarreled so violently over the room and the proper compensation for the work that the important relationship for Whistler was terminated. At one point, Whistler gained access to Leyland's home and painted two fighting peacocks meant to represent the artist and his patron; one holds a paint brush and the other holds a bag of money.

Whistler is reported to have said to Leyland, "Ah, I have made you famous. My work will live when you are forgotten. Still, per chance, in the dim ages to come you will be remembered as the proprietor of the Peacock Room." Adding to the emotional drama was Whistler's fondness for Leyland's wife, Frances, who separated from her husband in 1879.

Having acquired the centerpiece of the room, Whistler's painting of The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, American industrialist and aesthete Charles Lang Freer purchased the entire room in 1904 and had it installed in a room in his Detroit mansion. After Freer's death in 1919, the Peacock Room was permanently installed in the Freer Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.. The gallery opened to the public in 1923

Irrationalism and Aestheticism

Irrationalism and aestheticism were philosophical movements which formed as a cultural reaction against positivism in the early 20th century. These perspectives opposed or deemphasized the importance of the rationality of human beings. Instead, they concentrated on the experience of one's own existence.

Part of the movements involved claims that science was inferior to intuition. In this project, art was given an especially high place, as it was considered the gateway to the noumenon. The movement was not widely accepted by the public, as the social system generally limited access of the art to the elite (ie. a "Mandarin elitism").

Some of the followers of this idea are Fyodor Dostoevsky, Henri Bergson, Lev Shestov and Georges Sorel. Symbolism and existentialism grew out of these schools of thought.

Wikipedia

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me