Emile Gallé (1846-1904)

Emile Galle was the most important artist pursuing the naturalistic art which could enrich our day-to-day life in various forms and he became the dominant figure among the Art Nouveau movements. Here I intend to visualize his comprehensive artistic vision by showing his products development in main four areas chronologically.

He never made a naturalistic spoon however he certainly embraced the same vision on our enriched naturalistic life style.

Biography

In 1846 Emile Gallé was born in Nancy, France.

In 1846 Emile Gallé was born in Nancy, France.

His family managed a glass and earthenware factory, the Maison Gallé-Reinemer which was established in 1844 by a union between his father Charles Gallé (1818-1902), born in Paris, a traveling porcelain tradesman (and trained porcelain painter by using enamele) and his mother Fanny Reinemer (1825-1891), daughter of Marguerite and Jean Martin Reinemer, the owners of a crystal and porcelain shop in Nancy. In this eclectic family atmosphere Emile Gallé grew up and received his initial education.

After his secondary education at the Nancy couronnées du baccalauréat, he learned German, philosophy and botany and pursued research in mineralogy in Weimar from 1862 to 1866.

From 1866–7 he was employed by the Burgun, Schwerer & Cie glassworks in Meisenthal, France and learned the trades of glass and ceramics. Here he developed his knowledge of glass chemistry.

His approach is not merely theoretical and Emile is not afraid to learn to blow the glass. It adds to that a good knowledge of woodworking and especially the family passion for the natural sciences and especially for plants that leads to the drawing as a horticulturist.

In 1866, his father, Charles Gallé, was honoured with the title "By Emperor's appointment" for his glass making.

On his return to Nancy in 1870 he worked in his father's workshops at Saint-Clément where he composed a rustic dinner service with Victor Prouvé before hiring voluntarily as a soldier in the Franco-Prussian war. Émile Gallé leads a simple life, even austere. He studied on plants, animals and insects while he assisted his father. In the evening he reads poetry.

Enamelled glass Mosque Lamp by Philippe Joseph Brocard, 1867, Paris. In late nineteenth-century Europe, there was a great wave of interest in Islamic or Moorish art, which influenced many aspects of the applied arts and interior decoration. This vessel was inspired by the enamelled glass mosque lamps made during the twelfth to fourteenth centuries in Mamluk Egypt and Syria. British Museum.In 1871 he travelled to London to represent the family firm at the International Exhibition of 1871. During his stay he visited the decorative arts collections at the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria and Albert Museum), familiarizing himself with Chinese, Japanese and Islamic styles. He was particularly impressed with the Islamic enamelled ware, which influenced his early work. Also he visited the Botanical Gardens and learned exotic plants.

Enamelled glass Mosque Lamp by Philippe Joseph Brocard, 1867, Paris. In late nineteenth-century Europe, there was a great wave of interest in Islamic or Moorish art, which influenced many aspects of the applied arts and interior decoration. This vessel was inspired by the enamelled glass mosque lamps made during the twelfth to fourteenth centuries in Mamluk Egypt and Syria. British Museum.In 1871 he travelled to London to represent the family firm at the International Exhibition of 1871. During his stay he visited the decorative arts collections at the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria and Albert Museum), familiarizing himself with Chinese, Japanese and Islamic styles. He was particularly impressed with the Islamic enamelled ware, which influenced his early work. Also he visited the Botanical Gardens and learned exotic plants.

In the same year he travelled to Paris where he studied the art of ancient Syrian glass from Philippe-Joseph Brocard (1831-1896) who reproduced an enamelled glass Mosque lamp in 1867, and quasi-Chinese or Japanese art glass by Eugene Rousseau (1827-1890) in the period of Japonisme.

He returned to Nancy, with new paths of exploration of the art glass and it seeks to imitate nature with streaks, knots, splinters, reflections, shadows, mottled.

He superimposed layers of material and there interposed sheets of gold and silver. It raises bubbling and scratches.

In 1874, after his father's retirement, he took over the running of the Maison Gallé-Reinemer in Nancy from his father and immediately began to expand the business, proving himself an outstanding businessman as well as a designer of genius.

In 1875 he married Harriet Grimm.

EUGENE ROUSSEAU Enameled and applied glass vase in Japanese taste, engraved with aquatic plants enameled in green and applied with a school of fish. Losses to two fish. Base engraved E. Rousseau ParisHe participated in the Paris Exhibition of 1878 and won four gold medals. His career took off. At the International Exhibition of 1878 in Paris, the first was Joseph Brocard, who was studying the enamelling of glass and whose main ambition was to reproduce medieval Syrian glass. The second was Eugène Rousseau, a commissioning dealer in ceramics who had turned to glasswork at the end of the 1860s and was at the height of his achievement in the years around 1880.

EUGENE ROUSSEAU Enameled and applied glass vase in Japanese taste, engraved with aquatic plants enameled in green and applied with a school of fish. Losses to two fish. Base engraved E. Rousseau ParisHe participated in the Paris Exhibition of 1878 and won four gold medals. His career took off. At the International Exhibition of 1878 in Paris, the first was Joseph Brocard, who was studying the enamelling of glass and whose main ambition was to reproduce medieval Syrian glass. The second was Eugène Rousseau, a commissioning dealer in ceramics who had turned to glasswork at the end of the 1860s and was at the height of his achievement in the years around 1880.

His creations were exhibited at the great exhibitions and world fairs in Paris, Chicago and Saint Louis and were keenly collected by the most notable collectors of the day including Roger Marx, the editor of Gazette des beaux-arts, the industrialist Edouard Hannon, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Russian and Danish royal families (Carboni, S., and D. Whitehouse, Glass of the Sultans, New York, 2001, p.299).

Around 1882 he has assimilated the experiences of his youth.

In 1883 he enlarged his workshops of pottery, glassware and woodwork and many artists and craftsmen began to work for him. He opened more outlets and regularly exhibited his own works.

In 1884 he participated in the Exhibition at Paris and he won gold medals for his glassworks, wood cabinets, earthenwares and stonewares respectively.

At the Paris Exhibition of 1889 Gallé was awared Grand Prix for his glass works, a gold medal for his ceramics works and a silver medal for his funiture works and reached international fame. His style, with its emphasis on naturalism and floral motifs, was at the forefront of the emerging Art Nouveau movement. At this stage about three hundred artists and craftsmen were working for him.

In the same year he was made the officier de la Légion d'honneur.

He crystallized his ideas in his book Écrits pour l'art 1884-89 ("Writings on Art 1884-89"), which was published posthumously in 1908.

In 1893 he participated in the Chicago World's Fair.

In 1894 he opened his new glass factory and participated in the exhibition of decorative art of Nancy.

In 1897 he participated in the exhibition in Munich where he received a gold medal, and he exhibited in Frankfurt and London.

In 1900, at the Exposition Universelle de Paris 1900, he was awarded two Grand Prixs and a gold medal and also his collaboration Wild Rose got a bronze medal.

In the same year he was appointed Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneurby French government on 18th of May. He was admitted to the Academy of Stanislas in Nancy. He made an acceptance speech on the stage symboliste.

In 1901 he participated in the exhibition of Dresden.

In the same year he created the School of Nancy with Victor Prouvé, Louis Majorelle, Antonin Daum and Eugene Vallin and he became its chairman.

In 1902 he participated in the Exposition of Decorative Arts in Turin. Showered with honors and glory, he became a member of the Society of Beaux-Arts in Paris and several societies. It draws upon the request of Henry Galicia, then CEO of the house of Perrier-Jouet champagne, a bottle decorated with white anemones evoking Chardonnay.

In 1903 at the Exhibition at the Pavillon de Marsan in Paris, the vase Sycamore were co-sponsored by Wild Rose.

On 23 September 1904 he died of leukemia at the age of 58. He was buried in the cemetery of Preville, Nancy.

Many of Gallé works are kept at the Musée de l'École de Nancy.

Social Engagement

What is less well-known is Gallé's social engagement. He was a convinced humanist, and was involved in organizing evening schools for the working class (l’Université populaire de Nancy).

He was treasurer of the Nancy branch of the Ligue Française pour la Défense des Droits de l’Hommeand in 1898, at great risk for his business, one of the first to become actively involved in the defence of Alfred Dreyfus.

He also publicly condemned the Armenian genocide, defended the Romanian Jews and spoke up in defence of the Irish Catholics against Britain, supporting William O'Brien, one of the leaders of the Irish revolt.

In 1901 he founded École de Nancy(Alliance Provinciale des Industries d'art), an Art Nouveau movement with Victor Prouvé, Louis Majorelle, Antonin Daum and Eugène Vallin in the city of Nancy in Lorraine (France).

Workshop after Galle's death (1904)

In September 1904 Emile Gallé died leaving his wife to run the business. Henriette Gallé-Grimm took over the factory until 1914. The factory suspended its production duing the World War I. After Gallé’s death, important decisions were taken by members of the Gallé family, particularly Paul Perdrizet, his son-in-law who began producing Galle glass after 1918 once again, even adding new designs however primarily making the multi-layer cameo glass in floral and landscape designs.

The mass production of glassware was the only production kept going after the death of Emile Gallé, allowing the business to continue. Industrial production took over from artistic creation, assuring the commercial durability of the business. Management of the company was given to Emile Lang.

In 1909 the International Exhibition of Eastern France took place in Parc Sainte-Marie in Nancy. This major exhibition marked the start of the end for the Ecole de Nancy. The artists, regrouped in a pavilion created by Eugène Vallin, exhibited together for the last time.

At this time, Art Nouveau and the Ecole de Nancy were no longer considered as innovative. This was caused by a lack of creativity and renewal, a return to regionalism and tastes which evolved to simpler design and geometric forms.

From 1925, and particularly following the great crisis of 1929, the factory's activity slowed and at last stopped completely in 1931.

Only the shop located in rue de la Faïencerie continued to run, until 29th December 1935.

Personality

As with his research as an artist and business director, Gallé aimed to reach a higher level of being, that of the dialogue between sensitivity and conviction. On many of his works, he included an inscription, a message inviting us, and sometimes helping us, to interpret it.

The education Gallé received from his parents and grandparents was entirely orientated towards the love of the homeland. Gallé carried out research on beauty not only through his botanical expeditions but also through readings from which he drew references later applied to his works, particularly on the graphic glasswork. Some of his preferred authors were the romantic poets such as Théophile Gautier for the vase La pluie au bassin fait des bulles (The rain in the pond makes bubbles) and the vase Tetards (Tadpoles). But it was Victor Hugo whom he admired most; the great poet, but also the tutelary figure of republican France, intrigued the young man and was used as the principal source of reference with more than fifty quotations drawn from his works.

It was a young patriot bruised by the shameful failure of Sedan who enrolled himself in the French army. It was an injured boy from Lorraine who would make the German annexation of the Alsace-Moselle a recurrent theme in his production. Under the appearance of an almost lotharingist patriot (as had been his friend Maurice Barres), his work can be seen as a reminder of the family’s teachings that “people have the right to control themselves” as can be seen in the vase Espoir (Hope). All freedom scorned deserves combat and art was “his weapon for ideas” as shown in the table Sagittaire d’eau(Sagittarius of water).

In light of the Dreyfus affair, Emile Gallé did not hesitate to get himself involved from 1897, despite the risks incurred: friendship of Maurice Barrès, distrust and boycott of his clients and fellow citizens… But he was able to put up with it and went against the Reasons of State and the prevailing anti-Semitic racism as a free man.

The vases which appeared in the Universal Exhibition of 1900 were marked with quotations of a highly political nature: Gallé was of the same opinion as a quotation by Victor Hugo which he engraved on a vase for his friend Victor Prouvé in 1896: “Those who live are those who struggle, its those for whom a clear intention fills the soul and the brow”.

For Gallé, one belief lay hidden behind all these condemnations of human weakness: beyond the “fanaticism, hate, lies, prejudice, cowardice..” there is always hope. Like nature which forever comes back to life, Gallé thought that man could re-find his mind and unite to improve life. The peacefulness of nature seemed to be a refuge, constantly renewed, never deceiving and always the source of amazement in the eyes of the passionate nature-lover…In each of his references to creation, flora or fauna, Gallé thought of man, of his strengths and of his weaknesses, such as for the case Seulette suis, seulette veux etre (Lonesome I am, Lonesome I want to be). The figurative image was rare in the work of Gallé, giving it more substance. This is the case for the vase Les hommes noirs (Black men) for which Gallé collaborated with Victor Prouvé in order to broach the sensitive subject of the Dreyfus affair, an association which foreshadowed the future Alliance.

Gallé was involved in the creation of the Ligue de Défense des Droits de l’Homme et des Citoyens (League for the Defense of the Rights of Man and Citizens) in Nancy in 1898, and also in the foundation de l’Universelle Populaire. It was by fully taking on his role of manager, then founder of the Alliance Provinciale des Industries d’Art (Provincial Alliance of the Art Industry) that Gallé focused on social action as much as art. After fully undertaking the case of Dreyfus, Gallé continued to support the message launched by the Armenian community in France, notably with the dresser Le sang d’Arménie (Armenian blood) at the end of a career in which politics were so intimately embedded in the pieces created, allowing us to understand Gallé’s messages through his art unlike ever before.

Emile Gallé as Horticulturist

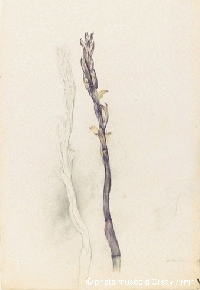

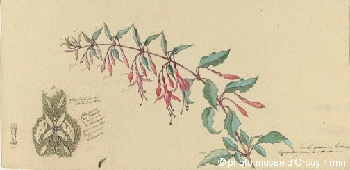

Fuchsia decoration for Vase. circa 1880. Ink, gouache heightened with white gouache. H: 20.7cm, W: 36.4cm. Musée d'OrsayAll the esthetical research, beyond historicism and eclecticism, focused on the study of nature, quintessential in the work of Gallé; his motto is actually “my roots are in wood”, an expression borrowed from a Dutch scholar, Jacob Moleschott. This motto shows the interest and passion that Gallé had for nature.

Fuchsia decoration for Vase. circa 1880. Ink, gouache heightened with white gouache. H: 20.7cm, W: 36.4cm. Musée d'OrsayAll the esthetical research, beyond historicism and eclecticism, focused on the study of nature, quintessential in the work of Gallé; his motto is actually “my roots are in wood”, an expression borrowed from a Dutch scholar, Jacob Moleschott. This motto shows the interest and passion that Gallé had for nature.

From the age of eighteen, he journeyed through the countryside of Lorraine and assembled his first collections of plants which he later used for decorative research. The umbellifer, for example, inspired not only the décor, but also the shape of the vase Heracleum and illustrates Gallé’s idea that form and décor should remain coherent and be part of the same objective: the unity of art.

His abilities, as well as his links with horticulturists and botanists in Nancy, led to him taking up the position of secretary within the “Société Centrale d’Horticulture” in Nancy, created in 1877.

|

|

Emille Gallé and Glass Making

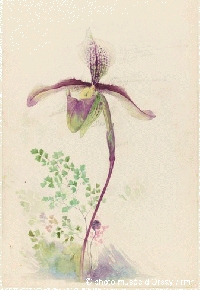

Orchid VaseGallé's three activities - glassmaking, Ceramic making and Wood Cbinet making - got him the nickname “homo triplex”, given to him by his friend Roger Marx.

Orchid VaseGallé's three activities - glassmaking, Ceramic making and Wood Cbinet making - got him the nickname “homo triplex”, given to him by his friend Roger Marx.

Glass working had a great importance for the Gallé family, especially for Emile. In 1866, Charles Gallé was honoured with the title “By Emperor’s appointment” for glass.

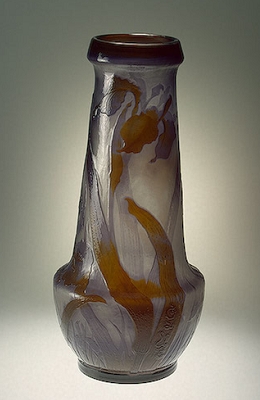

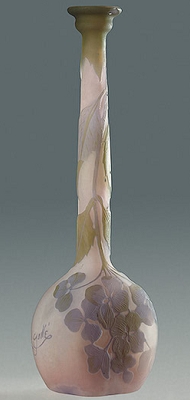

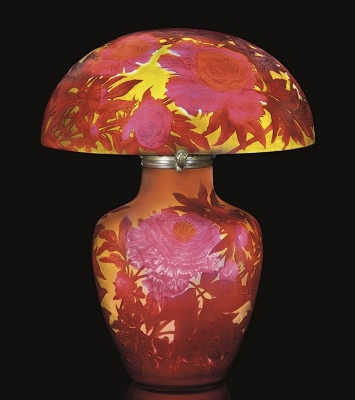

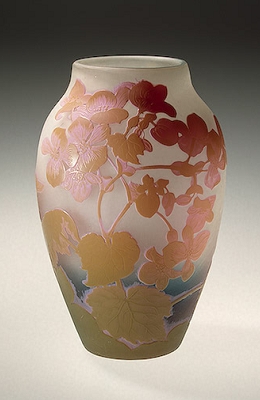

Throughout his life, Emile Gallé was dedicated to enriching his creations, and his research in techniques for glassmaking were vast. Glass, a material with many qualities, allowed the artist to demonstrate his talents for blowing, colouring and engraving. During the 8th exhibition of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, in Paris in 1884, focusing on the arts of glass and the land, Gallé was such a great success that all his pieces were sold within a month.

The techniques used by Gallé were numerous and more and more daring.

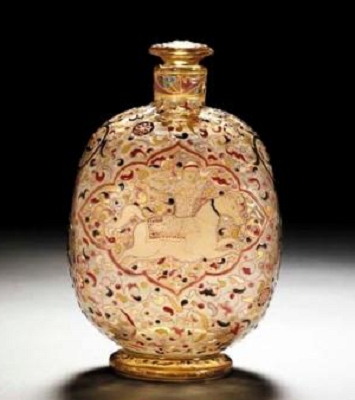

Enamelling

He used enamels to create elaborate compositions such as the vase “Ombelle” (Umbel). Gallé began to experiment with enamelling on glass in the late 1870s, drawing on the rich repertory of Ayyubid-Mamluk luxury glass whilst expanding on its decorative and chromatic range. In a statement to the jury of the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1889 he wrote: "Since 1878, I have devoted myself continually to developing a palette that would allow me to decorate glass with the aid of colours and low-temperature vitrifiable enamels ... I also developed reflecting colours by mixing them with hard Arabian enamels. Finally in 1884, I produced for the Union Centrale de Arts Décoratifs a new series of transparent enamels in relief ... I therefore present you today with the results of my continued research: opaque enamels with artificial and bizarre colours, muted nuances designed to add some 'spice' to an already impressive array of colours." (Warmus, W., Emile Gallé: Dreams into Glass, Corning, New York, 1984, p.185) The pink colour found on this bottle is an example of one of the new spicy hues developed by Gallé.

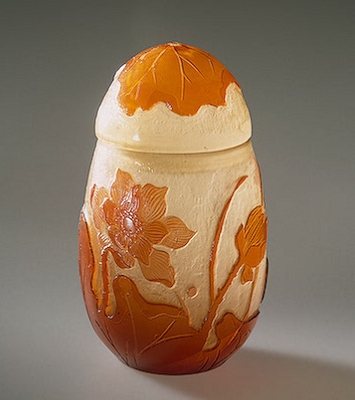

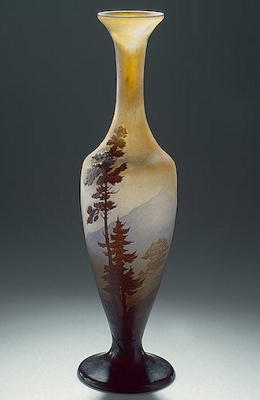

Acid Engraving

From 1889 he used the technique of engraving to engrave acid into multi-layered glass in order to reduce the engraving work done by wheel. This technique allowed a greater yield as the acid bath replaced weeks of work. This gain in time and productivity allowed more items to be distributed at a lower price.

Flaws of Glass

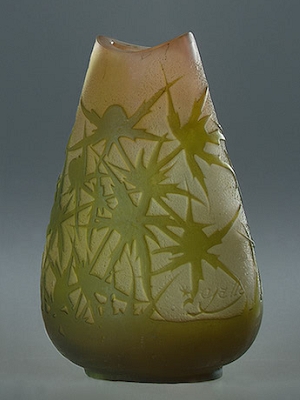

The patent in 1898 concerned patina on glass and crystal. The flaws of glass (dust and impurities) which can appear during its crafting are kept in order to become decorative elements, such as for the Pichet Le Pin (Pitcher the pine) by Emilie Gallé.

Marquetry of Glass

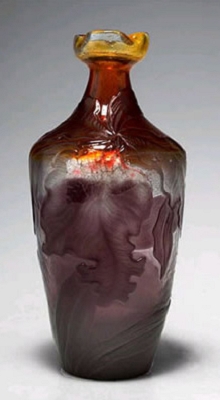

Vase model created in 1900

Multi-layered glass, marbled and partly hammered outer surface, glass marquetry and wheel engraving. H: 24.5cm W: 15cm. Musée d'Orsay. This vase is a perfect example of highly accomplished glass marquetry and an excellent demonstration of the possibilities offered by the technique.In the Spring of 1898, Emile Gallé patented the technique of glass marquetry. This process involved the incorporation of glass fragments of various thickness, shapes and colours into the still malleable, glass mass. This, combined with a multi-layering technique, equipped glass artists with an unlimited palette; besides the vast array of colours which could now be introduced into a decorative composition, each colour could also undergo subtle variations depending on where the coloured fragments lay in relation to the surface. Another advantage of the technique was that it facilitated the use of intricate and precise patterns as the coloured glass fragments could be cut to a chosen shape or engraved beforehand, according to the specifications of the master glazier.

Vase model created in 1900

Multi-layered glass, marbled and partly hammered outer surface, glass marquetry and wheel engraving. H: 24.5cm W: 15cm. Musée d'Orsay. This vase is a perfect example of highly accomplished glass marquetry and an excellent demonstration of the possibilities offered by the technique.In the Spring of 1898, Emile Gallé patented the technique of glass marquetry. This process involved the incorporation of glass fragments of various thickness, shapes and colours into the still malleable, glass mass. This, combined with a multi-layering technique, equipped glass artists with an unlimited palette; besides the vast array of colours which could now be introduced into a decorative composition, each colour could also undergo subtle variations depending on where the coloured fragments lay in relation to the surface. Another advantage of the technique was that it facilitated the use of intricate and precise patterns as the coloured glass fragments could be cut to a chosen shape or engraved beforehand, according to the specifications of the master glazier.

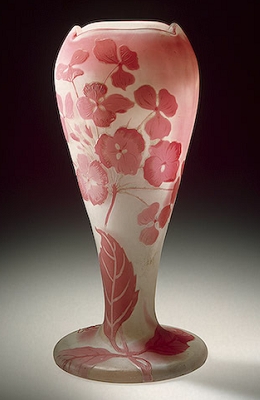

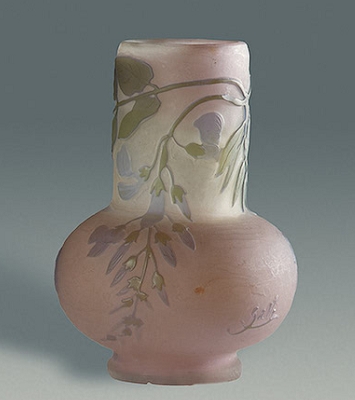

Glass Product Development - Chronological List

|

|

Emile Gallé and Cabinet Making

La Table du RhinFrom 1884 onwards, Emile Gallé showed an interest in cabinet-making. He explained his interest to the jury of the Universal Exhibition of 1889 in his own words: “for a long time, I have been passionate about woods, of oak with its robust and proud grain, of fragrant, fine walnut, of coppers shimmering on credenza of Lorraine, of spinning wheels from Vosges with delicate turnings.”

La Table du RhinFrom 1884 onwards, Emile Gallé showed an interest in cabinet-making. He explained his interest to the jury of the Universal Exhibition of 1889 in his own words: “for a long time, I have been passionate about woods, of oak with its robust and proud grain, of fragrant, fine walnut, of coppers shimmering on credenza of Lorraine, of spinning wheels from Vosges with delicate turnings.”

In 1885, he decided to create a cabinet-making studio – an area in which he had no previous experience – and, in 1889, he presented fourteen items of luxury furniture to the Universal Exhibition, the shapes of which were inspired by historical styles, fashionable at the time, such as the Table du Rhin, (Table of the Rhine) but whose marked and sculpted decorations on wood created a completely new style. Nature was no longer content to brighten up a room, but was there to merge into it and model it to its own shape.

The sideboard “Les Métiers” (The crafts) by Emile Gallé showed Gallé production at a time when family-run workshops started changing into art manufacturers, a change of scale which led to mass production. By using local materials, Gallé would show a deep attachment to his region, illustrated by the dresser “Les parfums d’autrefois” (The scents of the past), but he would also prove his excellent mastery of the techniques of marquetry and inlaying.

The some six hundred species of wood used gave him the chance to show nature's slightest variations in colour, in order to get as close as possible to representing it. Bit by bit, nature led Gallé to remove marked styles and instead use the form of a supple stem and a blossoming flower to create an innovative line, simple and modern, as shown by the “mobilier aux ombelles” (umbellate furniture), a tribute to the lessons of Japanese art.

Funiture Product Development

|

|

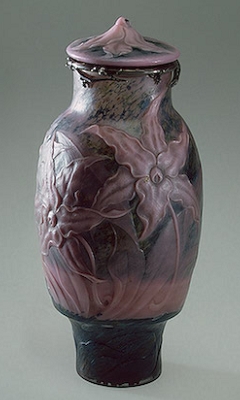

Emile Gallé and Ceramic Making

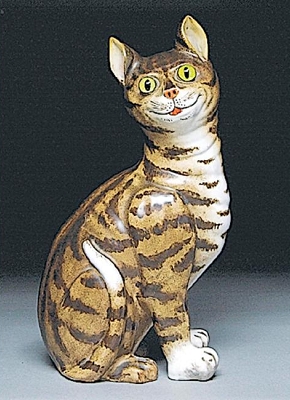

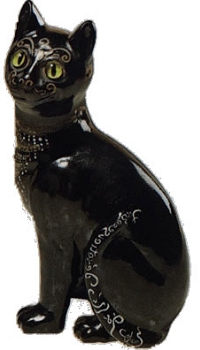

One of the cats made by Galle.While he always favoured glass, the material of dreams, Emile Gallé also dedicated some of his research to ceramics, an activity inherited from the traditions of Lorraine.

One of the cats made by Galle.While he always favoured glass, the material of dreams, Emile Gallé also dedicated some of his research to ceramics, an activity inherited from the traditions of Lorraine.

Even in the 16th century, earthenware factories existed in Lorraine, mainly producing tiles and pottery.

The legacy is rich, as much for the expertise and know-how as for the experimentation. Before the young Emile Gallé took over from his father, the Gallé company had been rewarded at the Universal Exhibition in 1861.

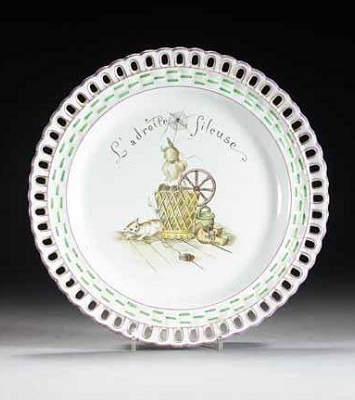

In 1878, the company exhibited tableware and various objects such as sweet boxes and ashtrays. The sources of inspiration were varied: the styles of Louis XV and Louis XVI, such as for the Berger (Shepherd) tableware, Persian and far-eastern styles, such as for the Cassolette tripode (tripodal Cassolette) later replaced by fauna and flora with the flower holder Ancolies (Columbine) and the vase Je suis fier de mes couleurs (I am proud of my colours).

Some items were offered in a variety of forms with different designs and various sizes due to the great success they met. This is the case of the ceramic cats which were sold over a period of thirty years. This was also the case of sets of tableware such as Berger (Shepherd) and Herbier (Herbarium) produced by Gallé which although receiving a gold medal at the Art Exhibition in 1884, became less popular with customers from 1889 onwards. Around 1892 Gallé limited the production of ceramics for economic reasons.

In 1902 for the marriage of his daughter Thérèse, Gallé created a last set of tableware entitled Service Fruits de mer (Seafood tableware).

Ceramics Product Development

Vase in 1885. Glazed Earthenware. H: 28.6cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vase in 1885. Glazed Earthenware. H: 28.6cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |  Pot in 1889. Earthenware, decorated in shades of gray and rose slowly to gray-white tin glaze. H: 17cm, W:19.5cm. Musée d'Orsay Pot in 1889. Earthenware, decorated in shades of gray and rose slowly to gray-white tin glaze. H: 17cm, W:19.5cm. Musée d'Orsay |

Faience Branch and Moon-Vase-Form Ewer, circa 1890. Underside with red-printed E, croix de Lorraine, G/depose, Nancy. H: 11 inch. Sold at $ 6000 in Dec 2003, Sotherby's. Faience Branch and Moon-Vase-Form Ewer, circa 1890. Underside with red-printed E, croix de Lorraine, G/depose, Nancy. H: 11 inch. Sold at $ 6000 in Dec 2003, Sotherby's. |

|

|

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me