Rococo Style

Rococo Style Originated in France

A portrait of Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764) by François Bouche,1756Rococo is an ornate style applied for art and interior design, originating in 18the century France under the reign of Louis XV (1705-1774)). Rococo rooms were designed as total works of art with elegant and ornate furniture, small sculptures, ornamental mirrors, and tapestry complementing architecture, reliefs, and wall paintings.

A portrait of Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764) by François Bouche,1756Rococo is an ornate style applied for art and interior design, originating in 18the century France under the reign of Louis XV (1705-1774)). Rococo rooms were designed as total works of art with elegant and ornate furniture, small sculptures, ornamental mirrors, and tapestry complementing architecture, reliefs, and wall paintings.

The word Rococo was originally used to describe the incrustation of artificial grottos and fountains in the gardens of Versailles. The word derived from the French rocaille which means stone, and coquilles meaning shell, due to reliance on these objects as motifs of decoration and the analogy of the Italian Barocco, meaning Baroque style. English use of the term began by 1836, when we read in Fraser's Magazine: There are two especial new mots di'argot, rococo and decousu.

Rococo appeared in France in about 1700, primarily as a style of interior design. The French Rococo exterior was most often simple, or even plain, but Rococo exuberance took over the interior. This characteristics of Rococo reflected the mental tendency of the French bourgeoise. After 72 years of the Louis XIV reign, there arose in Paris new types of private patrons -- nobles created by the sale of offices, nouveau riche tax collectors, and millionaires and bankers fat on the spoils of financing 25 years of disastrous wars. They luxuriated in a new artistic freedom, indulged their highly individualistic tastes, and welcomed fresh ideas in decoration. A society devoted to material comfort and preoccupied with personal pleasure demanded constant variety, surprise, and originality. The French nobles abandoned Versailles after 1715 for the pleasures of town life. The "hotels" (town houses) of Paris soon became the enters of a new, softer style we call "rococo." The feminine look of the Rococo style suggests that the age was dominated by the taste and the social initiative of women to a large extent it was. Women -- Madame de Pompadour (Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson: 1721–1764) in France, Maria Theresa in Austria (1717–1780), Elizabeth of Russia (1709-1762) and Catherine the Great (1729-1796) in Russia -- held some of the highest positions in Europe. The Rococo salon was the center of early 18th-centruy Parisian society, and Paris was the social center of Europe.

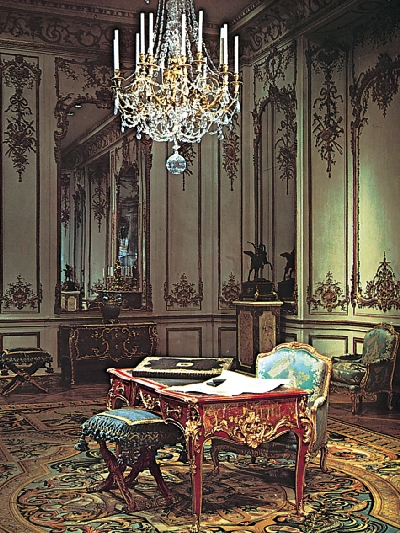

A delicacy of decorative motif in paneling and furniture characteristic of the Rococo design of the Louis XV style; room from the Hôtel de Varengeville, Paris.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkAt the outset the Rococo style represented a reaction against the ponderous design of Louis XIV’s Palace of Versailles and the official Baroque art of his reign. Several interior designers, painters, and engravers, among them Pierre Le Pautre (1648-1716), Juste Aurèle Meissonier (1695-1770), Jean Berain the Elder (1640-1711), and Nicolas Pineau (1684–1754), developed a lighter and more intimate style of decoration for the new residences of nobles in Paris. In the Rococo style, walls, ceilings, and moldings were decorated with delicate interlacings of curves and countercurves based on the fundamental shapes of the “C” and the “S,” as well as with shell forms and other natural shapes. Asymmetrical design was the rule. Light pastels, ivory white, and gold were the predominant colours, and Rococo decorators frequently used mirrors to enhance the sense of open space.

A delicacy of decorative motif in paneling and furniture characteristic of the Rococo design of the Louis XV style; room from the Hôtel de Varengeville, Paris.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkAt the outset the Rococo style represented a reaction against the ponderous design of Louis XIV’s Palace of Versailles and the official Baroque art of his reign. Several interior designers, painters, and engravers, among them Pierre Le Pautre (1648-1716), Juste Aurèle Meissonier (1695-1770), Jean Berain the Elder (1640-1711), and Nicolas Pineau (1684–1754), developed a lighter and more intimate style of decoration for the new residences of nobles in Paris. In the Rococo style, walls, ceilings, and moldings were decorated with delicate interlacings of curves and countercurves based on the fundamental shapes of the “C” and the “S,” as well as with shell forms and other natural shapes. Asymmetrical design was the rule. Light pastels, ivory white, and gold were the predominant colours, and Rococo decorators frequently used mirrors to enhance the sense of open space.

Excellent examples of French Rococo are the Salon de M. le Prince (completed 1722) in the Petit Château at Chantilly, decorated by Jean Aubert (1680-1741), and the salons (begun 1732) of the Hôtel de Soubise, Paris, by Germain Boffrand (1667-1754). The Rococo style was also manifested in the decorative arts. Its asymmetrical forms and rocaille ornament were quickly adapted to silver and porcelain, and French furniture of the period also displayed curving forms, naturalistic shell and floral ornament, and a more elaborate, playful use of gilt-bronze and porcelain ornamentation.

Juste Aurèle Meissonier (1695-1750), an Italian who came to Paris in 1723, is credited with being largely responsible for developing the Rococo style. He worked as a goldsmith, sculptor, painter, architect, and furniture designer in Paris and produced a famous book of engraved rococo designs 'Livres d'ornements en trente pieces and Ornements de la carte chronologique'. His Italian origin and training were probably responsible for the extravagance of his decorative style. He shared, and perhaps distanced, the meretricious triumphs of Oppenard and Germain, since he dealt with the Rococo in its most daring and flamboyant developments. He built houses not only as an architect, but also as a painter and a decorator covered their internal walls; he designed the furniture and the candlesticks, the silver and the decanters for the table; he was as ready to produce a snuff-box as a watch case or a sword hilt. Not only in France, but for the nobility of Poland, Portugal and other countries who took their fashions and their taste from Paris, he made designs.

His work in gold and silver-plate was often graceful and sometimes bold and original.

He was least successful in furniture, where his twirls and convolutions, his floral and rocaille motives were conspicuous.

He was appointed by Louis XV Dessinateur de la chambre et du cabinet du roi; the post of designer pour les pompes funèbres et galantes was also held along with that of Orfèvre du roi.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767Rococo painting in France began with the graceful, gently melancholic paintings of Antoine Watteau, culminated in the playful and sensuous nudes of François Boucher, and ended with the freely painted genre scenes of Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Rococo portraiture had its finest practitioners in Jean-Marc Nattier and Jean-Baptiste Perroneau. French Rococo painting in general was characterized by easygoing, light-hearted treatments of mythological and courtship themes, rich and delicate brushwork, a relatively light tonal key, and sensuous colouring. Rococo sculpture was notable for its intimate scale, its naturalism, and its varied surface effects.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767Rococo painting in France began with the graceful, gently melancholic paintings of Antoine Watteau, culminated in the playful and sensuous nudes of François Boucher, and ended with the freely painted genre scenes of Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Rococo portraiture had its finest practitioners in Jean-Marc Nattier and Jean-Baptiste Perroneau. French Rococo painting in general was characterized by easygoing, light-hearted treatments of mythological and courtship themes, rich and delicate brushwork, a relatively light tonal key, and sensuous colouring. Rococo sculpture was notable for its intimate scale, its naturalism, and its varied surface effects.

The term Rococo is sometimes used to denote the light, elegant, and highly ornamental music composed at the end of the Baroque period—i.e., from the 1740s until the 1770s. The earlier music of Joseph Haydn and of the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart can thus be termed Rococo, although the work of these composers more properly belongs to the emerging Classical style.

The Rococo style is characterized by freely handled S-shaped curves; the harmonious combination of naturalistic motifs, such as sprigs of flowers, with unrepresentational ornament, often reminiscent of splashing water; a tendency towards asymmetry; and a preference for the delicately poised to the solidly square set form. Irrational conjunctions of distorted curves are characteristic - derived from rocaille or the cleft, scalloped shell work and rockwork, and from the fantastic forms of exotic seashells (called coquillage) which were collected and highly prized. Unlike other styles, Rococo first appeared in the decorative arts and only later affected painting, sculpture, and architecture. Conceived originally in two dimensions, Rococo long remained a linear art, even when it was developed in France by highly skilled carvers, who occasionally borrowed and incorporated Chinese decorative motifs, for there was a subtle affinity between the Rococo style and ancient Chinese culture. Although the style came within the framework of classical design, it was essentially asymmetrical, and the French master carvers who translated it into three dimensions were ornamentalists with a taste for elegant complexity. The cross-fertilization of French Rococo and Chinese art liberated a gift for fantasy that was intemperately indulged, though seldom in England.

The Rococo Basilica at Ottobeuren (Bavaria): architectural spaces flow together and swarm with lifeFrom France the Rococo style spread in the 1730s to the Catholic German-speaking lands, where it was adapted to a brilliant style of religious architecture that combined French elegance with south German fantasy as well as with a lingering Baroque interest in dramatic spatial and plastic effects. Some of the most beautiful of all Rococo buildings outside France are to be seen in Munich—for example, the refined and delicate Amalienburg (1734–39), in the park of Nymphenburg, and the Residenztheater (1750–53; rebuilt after World War II), both by François de Cuvilliés. Among the finest German Rococo pilgrimage churches are the Vierzehnheiligen (1743–72), near Lichtenfels, in Bavaria, designed by Balthasar Neumann, and the Wieskirche (begun 1745–54), near Munich, built by Dominikus Zimmermann and decorated by his elder brother Johann Baptist Zimmermann. G.W. von Knobelsdorff and Johann Michael Fischer also created notable buildings in the style, which utilized a profusion of stuccowork and other decoration.

The Rococo Basilica at Ottobeuren (Bavaria): architectural spaces flow together and swarm with lifeFrom France the Rococo style spread in the 1730s to the Catholic German-speaking lands, where it was adapted to a brilliant style of religious architecture that combined French elegance with south German fantasy as well as with a lingering Baroque interest in dramatic spatial and plastic effects. Some of the most beautiful of all Rococo buildings outside France are to be seen in Munich—for example, the refined and delicate Amalienburg (1734–39), in the park of Nymphenburg, and the Residenztheater (1750–53; rebuilt after World War II), both by François de Cuvilliés. Among the finest German Rococo pilgrimage churches are the Vierzehnheiligen (1743–72), near Lichtenfels, in Bavaria, designed by Balthasar Neumann, and the Wieskirche (begun 1745–54), near Munich, built by Dominikus Zimmermann and decorated by his elder brother Johann Baptist Zimmermann. G.W. von Knobelsdorff and Johann Michael Fischer also created notable buildings in the style, which utilized a profusion of stuccowork and other decoration.

In Italy the Rococo style was concentrated primarily in Venice, where it was epitomized by the large-scale decorative paintings of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. The urban vistas of Francesco Guardi and Canaletto were also influenced by the Rococo. Meanwhile, in France the style had already begun to decline by the 1750s when it came under attack from critics for its triviality and ornamental excesses, and by the 1760s the new, more austere movement of Neoclassicism began to supplant the Rococo in France.

Rococo Style in England

In England Rococo was always thought of as the "French taste" and was never widely adopted as an architectural style, although its influence was strongly felt in such areas as silverwork, porcelain, and silks, and furniture.

Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779)

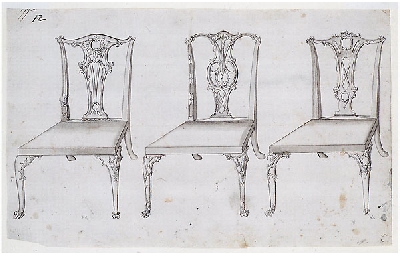

Thomas Chippendale, Drawing for three chairs, 1753Thomas Chippendale was a London cabinet-maker and furniture designer in the mid-Georgian, English Rococo styles. He went to London in 1749 where, in 1754, he became the first cabinet-maker to publish a book of his designs, titled The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director.

Thomas Chippendale, Drawing for three chairs, 1753Thomas Chippendale was a London cabinet-maker and furniture designer in the mid-Georgian, English Rococo styles. He went to London in 1749 where, in 1754, he became the first cabinet-maker to publish a book of his designs, titled The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director.

He transformed English furniture design through his adaptation and refinement of not only the Rococo style but also Gothic, Chinoiserie and Neoclassic. From the 1760's Chippendale was influenced heavily by the Neoclassical work of architect Robert Adam, with whom he worked on several large projects, notably at Harewood House and Nostell Priory. Recognizably "Chippendale" furniture was produced in Dublin and Philadelphia, as might be expected, but also in Lisbon, Copenhagen, and Hamburg. Catherine the Great and Louis XVI both possessed copies of the Director in its French edition.

Many of the pieces that were rococo in form—mirrors, pier tables, and torchères—by Chippendale, Thomas Johnson, John Linnell, and others were done in gilt gesso over sculpted wood, showing the influence of stucco workers and other Continental-trained sculptor-modelers.

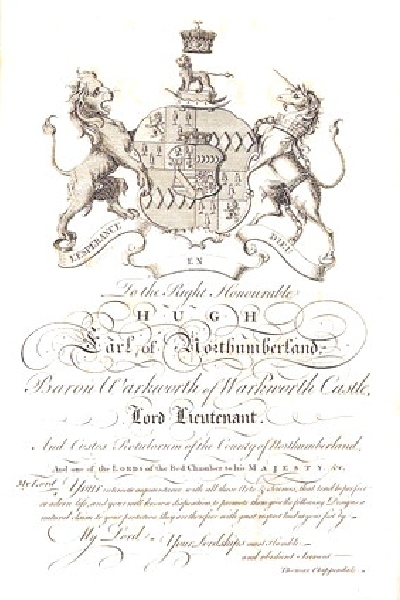

Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director, second edition, 1755

Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director, second edition, 1755Chippendale type side-chair, Walnut, circa 1750 from my room.

Paul de Lamerie (1688 - 1751)

Maynard Master's style ewer and dish, marked by Paul de Lamerie, arms of Mountrath, 1742, Gilbert CollectionPaul de Lamerie (1688 - 1751) was a talented and innovative silversmith who first began working in the Rococo style in the 1730s. He was born in the United Provinces (Netherlands) to French Huguenot parents, who had left France following the Edict of Fontainebleau (1685) and initially settled there. They moved to London in 1691. He opened his shop at 24 years old in 1712 and was appointed goldsmith to George I in 1716. Lamerie is notable for working in the Rococo style from the 1730s with commissions from many aristocratic patrons. The most highly regarded silversmith of his day, his fame survived him, giving him a lasting influence on British silver.

William Hogarth (1697-1764)

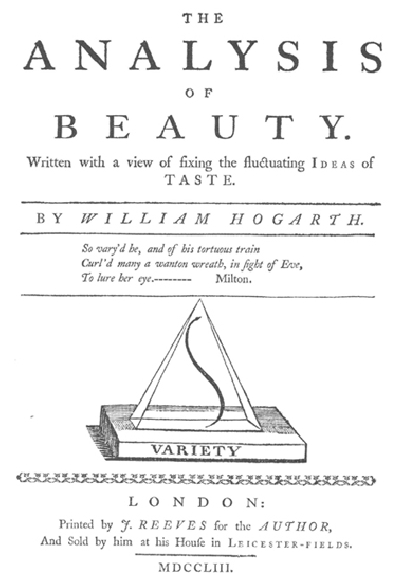

William Hogarth "Analysis of Beauty", 1753William Hogarth (1697-1764) helped develop a theoretical foundation for Rococo beauty. Though not intentionally referencing the movement, he argued in his Analysis of Beauty (1753) that the undulating lines and S-curves as the prominent in Rococo were the basis for grace and beauty in art or nature (unlike the straight line or the circle in Classicism). The development of Rococo in England is considered to have been connected with the revival of interest in Gothic architecture early in the 18th century.

William Hogarth "Analysis of Beauty", 1753William Hogarth (1697-1764) helped develop a theoretical foundation for Rococo beauty. Though not intentionally referencing the movement, he argued in his Analysis of Beauty (1753) that the undulating lines and S-curves as the prominent in Rococo were the basis for grace and beauty in art or nature (unlike the straight line or the circle in Classicism). The development of Rococo in England is considered to have been connected with the revival of interest in Gothic architecture early in the 18th century.

In the 1730s, Hogarth founded St. Martin’s Lane Academy, a drawing and design school that heavily influenced makers and modelers of silver, ceramics, and furniture. Hubert-François Gravelot, a French-born designer, taught St. Martin’s students the latest in French rococo design and the importance of drawing skills for a variety of media.

The End of Rococo

The beginning of the end for Rococo came in the early 1760s as figures like Voltaire and Jacques-François Blondel began to voice their criticism of the superficiality and degeneracy of the art. Blondel decried the "ridiculous jumble of shells, dragons, reeds, palm-trees and plants" in contemporary interiors.

By 1785, Rococo had passed out of fashion in France, replaced by the order and seriousness of Neoclassical artists like Jacques Louis David. In Germany, late 18th century Rococo was riduculed as Zopf und Perücke ("pigtail and periwig"), and this phase is sometimes referred to as Zopfstil. Rococo remained popular in the provinces and in Italy, until the second phase of neoclassicism, "Empire style," arrived with Napoleonic governments and swept Rococo away.

Rococo Revival

There was a renewed interest in the Rococo style between 1820 and 1870, and this movement is mentioned as "Rococo Revival". The English were among the first to revive the "Louis XIV style" as it was miscalled at first, and paid inflated prices for second-hand Rococo luxury goods that could scarcely be sold in Paris. But prominent artists like Delacroix and patrons like Empress Eugénie also rediscovered the value of grace and playfulness in art and design.

Characteristics of Rococo style

Natural motifs

Natural motifs are a feature of both British and French Rococo. However, in British Rococo designs the natural motifs are often more realistic in their details than those on French Rococo designs.

Natural motifs are a feature of both British and French Rococo. However, in British Rococo designs the natural motifs are often more realistic in their details than those on French Rococo designs.

Elaborate carved forms

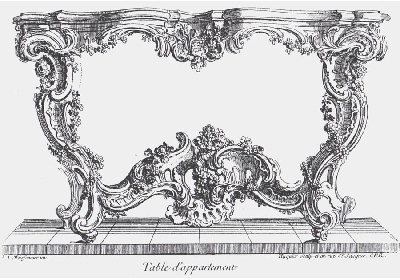

Design for a table by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, Paris ca 1730Rococo was a style developed by craftspeople and designers rather than architects. This helps to explain the importance of hand-worked decoration in Rococo design.

Design for a table by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, Paris ca 1730Rococo was a style developed by craftspeople and designers rather than architects. This helps to explain the importance of hand-worked decoration in Rococo design.

Asymmetry

Abstract and asymmetrical Rococo decoration: ceiling stucco at the Neues Schloss, TettnangRococo design is often not symmetrical - one half of the design does not match the other half.

Abstract and asymmetrical Rococo decoration: ceiling stucco at the Neues Schloss, TettnangRococo design is often not symmetrical - one half of the design does not match the other half.

S and C scrolls

Curved forms are common in Rococo. They often resemble the letters 'S' and 'C'.

Rocaille

Rocaille (pronounced 'rock-eye') takes various forms. Sometimes it looks like a piece of frilly carving. At other times it looks like some form of water or eroded rock. The stylised 'icicles' on the candlestand resemble stalactites, while on the chocolate pot and clock the rocaille looks more like shells.

Acanthus leaf

The acanthus leaf is one of the basic motifs of Rococo design. It is not very closely related to a real acanthus leaf (Acanthus mollis), but is rather a stylised version of it.

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me