Rococo Naturalism

Realism - Japanese Palace Project and Johann Joachim Kaendler at Meissen Porcelain Factory

Realism - the passion to imitate natural forms as precisely as possible which was inspired by scientific interest - would be derived from this extraordinary project making so many porcelain animals and birds to decorate the Japanese Palace in Dresden ordered by Augustus the Strong (1694/7-1733), Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, one of the wealthiest monarchs and most important patrons of the arts of his age. Now we can see the surprising super-real porcelain animals and birds could be only achieved by the genius hands of Johann Joachim Kaendler, the most famous modeler in the porcelain history. The realism is one of the key components of Rococo Naturalism.

Japanese Palace Project

Bird of Paradice by Johann Joachim Kandler, 1742.Various animal figures were made for Augustus the Strong. It is from a large group of animals and birds ordered the Meissen factory for the porcelain menagerie that Augustus planned for the upper floor of the Japanese Palace at Dresden.

Bird of Paradice by Johann Joachim Kandler, 1742.Various animal figures were made for Augustus the Strong. It is from a large group of animals and birds ordered the Meissen factory for the porcelain menagerie that Augustus planned for the upper floor of the Japanese Palace at Dresden.

Conceived in 1730, this was intended to complement his existing menagerie of live animals at the Moritzburg and his collection of stuffed animals at the Zwinger (both nearby in Dresden). The three collections were intended to demonstrate the Elector's culture and taste (porcelain sculptures), his power (live animals), and his scientific knowledge (taxidermic collections). The sculpture may have been based on a print or specimen in one of these collections.

The ambition of Augustus's project cannot be overemphasised, and it still remains unparalleled in the history of ceramics. The order for these large beasts came only 20 years after the foundation of the Meissen factory, the first European factory to succeed in the manufacture of 'true' (or hard-paste) porcelain of the Chinese type. Meissen's discovery of the means of making porcelain was the direct result of Augustus the Strong's passion for imported Far Eastern wares, which led him to amass a collection of over 20,000 pieces (among them 151 Chinese vases exchanged for a unit of 600 cavalrymen), and to employ, and briefly imprison, the alchemist J. F. Böttger to discover the formula for this 'white gold'.

In 1730, when the project was conceived, Meissen had made few large wares and had very little experience of sculptural production. Indeed, at this date no porcelain sculptures on the scale of the largest Japanese Palace animals had been attempted anywhere in the world.

The size of the project is also extraordinary. According to a list of 1734 as many as 597 animals and birds were projected for the palace. Most were to have been produced in editions of eight from moulds made from original models provided by the sculptors discussed below. While in the event this quantity of figures was not realised, an inventory lists as many as 458 examples at Dresden in 1736, but many were much smaller birds and animals than this piece. Not surprisingly, their production became such a drain on the factory’s output and resources that work on the scheme was abandoned sometime before 1739.

Making the Sculptures

The factory's arcanists – the men who prepared the porcelain formula and glaze – had to develop new porcelain body (or 'paste') for the production of these large animals, one that could bear the weight of the sculptures during the second, high temperature glaze firing, when the material softened in the kiln.

The factory's arcanists – the men who prepared the porcelain formula and glaze – had to develop new porcelain body (or 'paste') for the production of these large animals, one that could bear the weight of the sculptures during the second, high temperature glaze firing, when the material softened in the kiln.

The factory experimented considerably with the formula for the animals (which accounts for the variations in surface finish and colour), and the incised numbers on some examples indicate the variant used. Despite these efforts, most of the animals exhibit fire-cracks (particularly at the base, where the greatest stresses occurred during the firing).

All the Japanese Palace animals were formed in sections in hollow plaster piece moulds. Interestingly, for the production of the king vultures these moulded components were used in a number of different configurations (far more than on other animals), resulting in three variants: one bolt upright, (shown above left) another crouching (the V&A's version shown at the top of the page), and a third leaning forward but with lower legs extended (shown right).

The 'X' mark incised on the base of the V&A's sculpture is attributed to Andreas Shiefer, the factory craftsman who worked the clay in the piece-moulds and assembled the component parts prior to firing.

The Sculptors

The factory modeller Johann Gottlieb Kirchner had been put to work on the Japanese Palace project in 1730, and in the following year Johann Joachim Kaendler was taken on as Kirchner's assistant, specifically to provide models for the life-size animals. Kaendler – one of the most important figures in 18th-century ceramics, and arguably the greatest porcelain modeller of his era – later modelled many of the finest Meissen figures and wares, in doing so establishing the conventions that defined the porcelain figure as a sculptural genre. The majority of the models for the Japanese Palace animals were by Kaendler, as Kirchner was dismissed from Meissen in 1733. Some of Kaendler's earliest models for the commission were based on prints, but he made increasing use of the live animals in Augustus the Strong's collection – with the result that many of these later models are extraordinarily vigorous and naturalistic in modelling and conception, as with this vulture.

The model for this bird was created in 1731, soon after Kaendler was appointed, and although payments to him are recorded for modelling these 'Kropff Vogel' (literally 'crop bird'), it is possible that they were made in collaboration with Kirchner, as they show elements of the latter's style.

Genuin Modeler - Johann Joachim Kaendler (1706 – 1775)

Johann Joachim Kaendler was trained as a sculptor in Dresden and was destined to become the greatest German porcelain modeller, responsible for much of the success of the Meissen porcelain factory during the 18th century. It is a work of great skill and invention. Kandler found nothing too difficult to attempt and his efforts were extremely productive.

His works were naturalistic in style and imitated throughout Europe. He joined the factory in 1731 and produced seven large birds about four feet high and one of the apostles for the Japanese palace and was designing its table ware when the King died, his successor vowing to complete the task.

During his forty four years at Meissen the reputation of the factory reached dizzying heights. His elaborate vases were nothing short of sensational.

Decorating the sculpture

Augustus the Strong had specified that all the animals were to be in natural colours, but it was thought too risky to put the large models through the kilns for an enamel firing, so these larger sculptures were painted in unfired pigments by the court lacquerer, Christian Reinow. We know from Reinow's invoices that bright colours were used, but these have very rarely survived, as the pigments have discoloured over time, and on the majority of examples they have been completely removed. The survival of the bright green and red on this vulture is exceptional. The colours are mostly on the head, neck and wings, leaving large areas of white exposed. It is probable that much of the bird was left unpainted, as the colouring follows that of real king vultures, and as some of the later Japanese Palace birds with fired decoration have large areas of plumage left undecorated.

There is an excellent short book on the Japanese Palace animals, Samuel Wittwer's A Royal Menagerie: Meissen Porcelain Animals, published by the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, and J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 2000.

Victoria & Albert Museum

Relationship with Charles Frederick Kandler

Wine Cistern by Charles Frederick Kandler, 1734. This was made for the Westminster Bridge Lottery however someone (probably Paul de Lamerie) sold it to Catherine the Great, Tzar of Russia, and it remains in the Hermitage Museum, the largest extant piece of antique solid silver in the world. It is a huge folly, and a beautiful one: utterly dispensable yet extraordinary. In 1734 Paul de Lamerie was called on to produce his two great Chandeliers in the Kremlin. Charles Frederick Kandler was the greatest silversmith in 18th century however "the identity remains mystery" said Arthur G. Grimwade. Some scholars think that he was a youger brother of Johann Joachim Kaendler.

Wine Cistern by Charles Frederick Kandler, 1734. This was made for the Westminster Bridge Lottery however someone (probably Paul de Lamerie) sold it to Catherine the Great, Tzar of Russia, and it remains in the Hermitage Museum, the largest extant piece of antique solid silver in the world. It is a huge folly, and a beautiful one: utterly dispensable yet extraordinary. In 1734 Paul de Lamerie was called on to produce his two great Chandeliers in the Kremlin. Charles Frederick Kandler was the greatest silversmith in 18th century however "the identity remains mystery" said Arthur G. Grimwade. Some scholars think that he was a youger brother of Johann Joachim Kaendler.

Johann lived in London and had his own premises at Jarmyn Street in mid 1730s. His youger brother came form Dresden in about 1727, and took over his elder brother's premises at Jermyn Street.

This highly important silversmith had the finest modeling skills and worked for Paul de Lamerie, the most famous silversmith. Some of De Lamerie's works from 1736 to 1745 are mentioned as the excellence of Rococo style in England. His works of arts surpassed all and he became known to be "Maynard Master".

Tradition of Saxony Sculpture since 13th century

Aquamanile in the Form of a Cock, Lower Saxony, 13century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.This aquamanile made in 13th century, lower Saxony, takes the form of a crowing cock. This is one of the direct source of Rococo Naturalism because Johan Jaohim Kaendler, the most famous modeler established Rococo style at Meissen, grown up in this tradition of Saxony sculpure.

Aquamanile in the Form of a Cock, Lower Saxony, 13century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.This aquamanile made in 13th century, lower Saxony, takes the form of a crowing cock. This is one of the direct source of Rococo Naturalism because Johan Jaohim Kaendler, the most famous modeler established Rococo style at Meissen, grown up in this tradition of Saxony sculpure.

Balanced on its two feet, the rooster has an extended neck and an open beak. The vessel is filled through an opening with a hinged lid found between the carefully rendered upright tail feathers, and a pair of feathers curls forward to form the handle. The water was poured through the open mouth.

Aquamanilia in this form are rare, but this example can be closely compared to two others, one in Frankfurt and another in Nuremberg. The three works are all strikingly naturalistic renderings of the rooster, with densely engraved feather patterns over much of their surfaces. Only in the New York example, however, was the modeler bold enough to balance the bird on its feet. Both of the others use the extended rear feathers to create a tripod for greater stability.

Source: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Origination by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695-1750)

Johann Joachim Kaendler tried to imitate live animals and birds as precisely as possible however he did not intend to apply their real figures on dairy utensils, at least at the first stage of Japanese Palace project. And also the syle of figures were Sientific Realism rather Rococo Naturalism. The origination of Rococo Naturalism could be attributed to Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695-1750), an unruly genius Italian active in Paris.

Tureens by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier in 1734

A Silver Tureen, Stand and Cover designed by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, executed by Pierre-François Bonnestrenne and Henry Adnet, Paris, 1735-1740. (36.9 by 45.6 by 38 cm.)Two covered tureens created for the Duke of Kingston in 1734/35 clearly illustrates that the invention of Rococo naturalism could be traced back to its French origin directly. This is designed by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, who was described by one of his contemporaries as "an unruly genius, and, what's more, spoilt by Italy", active as a goldsmith, sculptor, painter, architect, designer for porcelain and furniture designer in Paris. He is often considered the leading originator of the influential Rococo style in the decorative arts. Each tureen bears Meissonnier's engraved signature in acknowledgment of his responsibility for both its design and execution. For the actual making of the tureens Meissonnier employed two Parisian silversmiths, Henry Adnet (1683-1745) and Pierre-François Bonnestrenne (1682?-after 1740).

A Silver Tureen, Stand and Cover designed by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, executed by Pierre-François Bonnestrenne and Henry Adnet, Paris, 1735-1740. (36.9 by 45.6 by 38 cm.)Two covered tureens created for the Duke of Kingston in 1734/35 clearly illustrates that the invention of Rococo naturalism could be traced back to its French origin directly. This is designed by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, who was described by one of his contemporaries as "an unruly genius, and, what's more, spoilt by Italy", active as a goldsmith, sculptor, painter, architect, designer for porcelain and furniture designer in Paris. He is often considered the leading originator of the influential Rococo style in the decorative arts. Each tureen bears Meissonnier's engraved signature in acknowledgment of his responsibility for both its design and execution. For the actual making of the tureens Meissonnier employed two Parisian silversmiths, Henry Adnet (1683-1745) and Pierre-François Bonnestrenne (1682?-after 1740).

Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier began each of his models for this commission with a real sea shell, turning it into the vessel's body. The shape of the lid is likewise adapted from a shell, upon which the animals and vegetables are placed to harmonize with the oval tureen and its platter. The latter itself becomes a perfect example of an asymmetric cartouche, of which the underside is perhaps even more remarkable than the upper. Vegetables are integrated into the platter's undulating border of concave and convex forms. When assembled, the three elements of platter, tureen and lid create a completely novel effect: a harmonious and balanced whole, without beginning or end.

"Meissonier's Kingston tureens encompassed all the latest technical achievements, social vogues and aesthetic innovations," writes Ubaldo Vitali in the same catalogue. "They are very complex equations of their time and place. Their coefficients, variables and quantities are totally interconnected and should not therefore be analyzed independently. For instance, his use of natura which in some cases was actually molded from life, cannot be understood outside of the social fashions and scientific interests of the early eighteenth century, just as the full impact of his invenzione can only be appreciated within the context of the intellectual history of the 1730s in Paris.

"The Kingston tureens," concludes Vitali, "encapsulate the many complex facets of Meissonnier's persona. They are the creation of one of the most innovative minds of the time. In his hands art and technique worked together for a perfect balance and harmony."

One of the tureen was auctioned at Sothrby's in 1998 and its estimate value was US$8,000,000-12,000,000.

Rococo Design Book by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier

This etching "PROJET…D’UN GRAND SURTOUT DE TABLE ET LES DEUX TERRINES… EXECUTÉS POUR MILLORD DUC DE KINGSTON IN 1735 (Design for a centerpiece and two tureens for the duke of Kingston in 1735), PLATE 115 IN OEUVRE DE JUSTE-AURÈLE MEISSONNIER" is an original design of the above mentioned Covered Tureen and Platter in the Cleaveland Museum of Art. This is designed by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695-1750), and etched by Gabriel Huquier (French, 1695–1772). Etching on white laid paper, France, 1748 (designed 1735). Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council.

This etching "PROJET…D’UN GRAND SURTOUT DE TABLE ET LES DEUX TERRINES… EXECUTÉS POUR MILLORD DUC DE KINGSTON IN 1735 (Design for a centerpiece and two tureens for the duke of Kingston in 1735), PLATE 115 IN OEUVRE DE JUSTE-AURÈLE MEISSONNIER" is an original design of the above mentioned Covered Tureen and Platter in the Cleaveland Museum of Art. This is designed by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695-1750), and etched by Gabriel Huquier (French, 1695–1772). Etching on white laid paper, France, 1748 (designed 1735). Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council.

Design for Porcelaine at Chantilly by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier

Tea Service, Chantilly Porcelain Manufactory, about 1730 - 1735

Soft-paste porcelain, polychrome enamel decorationIn latter half of 1720s, Juste Aurèle Meissonier began designing and modeling for porcelain producted at Manufacture de Porcelaine at Chantilly, under patronage of Louis-Henri (1692-1740), Prince de Condé. Meissonnier's first essays in the genre were for his patron the Prince de Condé.

Tea Service, Chantilly Porcelain Manufactory, about 1730 - 1735

Soft-paste porcelain, polychrome enamel decorationIn latter half of 1720s, Juste Aurèle Meissonier began designing and modeling for porcelain producted at Manufacture de Porcelaine at Chantilly, under patronage of Louis-Henri (1692-1740), Prince de Condé. Meissonnier's first essays in the genre were for his patron the Prince de Condé.

Manufacture de Porcelaine at Chantilly was founded in 1725 by Ciquaire Cirou (ca.1700-1751), under the patronage of Louis-Henri (1692-1740), Prince de Condé, as appears by a letter patent. It is after his failure as Louis XV's chief minister forced him out of Paris in 1726 that Prince de Condé established a porcelain factory at his château at Chantilly.

Condé was an avid collector of East Asian porcelains, both Chinese and Japanese, and his Chantilly manufactory's first decade of output showed the marked influence of Arita porcelain, particularly in the "Kakiemon" palette of soft iron red and blue-green. A patent granted to the factory in 1735 by Louis XV specifically describes the right to make porcelain façon de Japon, "in imitation of the porcelain of Japan;" its reference to ten years' successful experiment on the part of Ciquaire Cirou is the basis for dating the factory's origins to 1725, found in many sources. The factory had developed its own whimsical interpretations of Asian motifs, combining an exotic dragon and monkey with European flowers. The Chantilly pattern was a great favorite for ordinary services, also called Barbeau, a small blue flower runnning over the white paste.

(Above) This mark, with the Chantilly name at length, is on a porcelain plate, white ground, with blue springs of flowers. (Below) The mark of Pigorry, who resusciated the factory in 1803. When Ciquaire Cirou died in 1751, Chantilly passed into the hands of Messrs. Peyrard, Aran and Antheaumre de Surval, who continued it successfully until the Revolution in 1789, when it was closed. In 1803, the Mayor of Chantilly, M Pigorry, opened a new porcelain fabrique, principally for domestic vessels, dinner and tea services. He was succeeded by MM Bougon and Chalot. In 1893, while under the direction of Potter, a fayance was produced in imitation of the English, and especially of the productions of Wedgwood.

(Above) This mark, with the Chantilly name at length, is on a porcelain plate, white ground, with blue springs of flowers. (Below) The mark of Pigorry, who resusciated the factory in 1803. When Ciquaire Cirou died in 1751, Chantilly passed into the hands of Messrs. Peyrard, Aran and Antheaumre de Surval, who continued it successfully until the Revolution in 1789, when it was closed. In 1803, the Mayor of Chantilly, M Pigorry, opened a new porcelain fabrique, principally for domestic vessels, dinner and tea services. He was succeeded by MM Bougon and Chalot. In 1893, while under the direction of Potter, a fayance was produced in imitation of the English, and especially of the productions of Wedgwood.

The mark is a hunting horn in blue or red, frequently accompanied by a letter, indicating the pattern or initial of the painter. Sometimes, the horn is impressed and marked in blue on the same piece. The decoration of Chantilly porcelain is very slight, generally in the old Japanese style, or in detached springs of flowers and blue, but occasionally such subjects as a hawking party or landscape. P.L. mark, accompanying the horn is mentioned, which diiffers from the cursive P. on the piece at South Kensington. The initial letter is in gold. The horn is sometimes red and sometimes blue.

English Rococo Naturalism and Paul de Lamerie

Set of Four Salts and Spoons by Paul de Lamerie, London, 1739. These salts were acquired by Clark with two identical copies supplied by a victorian silversmith Paul Storr in 1819A set of four cast salts with accompanying spoons illustrates the marriage of naturalism and fantasy so characteristic of the rococo style. Each salt is conceived as a abalone shell supported by a mermaid draped in netting, encrusted with sea shells and coral. Sea shell and coral spoons

continue the marine theme.

This style was introduced by Maynard Meister who worked for Paul de Lamerie from 1736 to 1745. The Maynard Meister might be Charles Frederick Kandler whose elder brother, Johan Jaohim Kaendler, was the most famouse modeler at Meissen Porcelain Manufacture. It was he that originated Rococo Naturalism in Germany by creating animal figures by porcelain, which was derived from the mixture of Saxony Sculpure tradition and Japanese Imari porcelain. He lived at Jermyn Street in London in the mid 1730s and tought the modeler skills to his youger brother, Charles Frederick Kandler, who was Maynard Master established the golden age of English Rococo style.

The four salts, marked by Paul de Lamerie in 1739/40, were acquired by Clark in 1930 with two identical copies by Paul Storr (1771-1844) dated 1819/20. Storr borrowed freely from de Lamerie's work and is known to have supplemented objects originally supplied by the earlier goldsmith.

(1) For examples, see Arthur Grimwade, "Family Silver of Three Centuries," Apollo, vol. 82 (December 1965), p. 500, Fig. 4; and Arthur G. Grimwade, The Queen's Silver, A Survey of Her Majesty's Personal Collection (The Connoisseur, London, 1953), Pl. 17.

Silver in the Clark Art Institute - Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Magazine Antiques, Oct, 1997 by Beth Carver Wees

English Rococo Naturalism and Nicholas Sprimont

Two pairs of salts for Prince of Wales in the Royal Collection made by Nicholas Sprimont (1716-1771) is a great monument in the history of English Rococo Naturalism.

Two pairs of salts for Prince of Wales in the Royal Collection made by Nicholas Sprimont (1716-1771) is a great monument in the history of English Rococo Naturalism.

The salts are struck with the maker's mark of Nicholas Sprimont, a Liègeois Huguenot who appears to have moved to London early in 1742, where he became a leading practitioner of the rococo style. Sprimont's silver is exceptionally rare and these salts are among the best-known examples of his work.

It has been suggested that the striking naturalism of these two pairs of salts was achieved by casting actual seashells, crabs and crayfish from life. They were almost certainly supplied for the Marine Service of Frederick, Prince of Wales, in the early 1740s. Sprimont appears to have worked only with silver for six or seven years. From c.1745 he was involved with the establishment of the Chelsea porcelain factory. The crayfish salt served as a model for porcelain versions subsequently reproduced by the factory.

The accompanying spoons are modelled as branches of coral with cockleshell bowls; they are illustrated here resting inside the bowls of the salts. The spoons, which are unmarked, appear on an undated sheet of designs attributed to Sprimont for a salt cellar with alternate spoons discovered in a collection of seventy-eight sheets of drawings in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Two pairs of salts by Nicholas Sprimont, 1742-3, Crab salts 8.9 x 17.8 x 11.7 cm; crayfish salts 8.7 x 14 x 14.1; spoons 11 cm long, The Royal CollecionLondon hallmarks for 1742-3 and maker's mark of Nicholas Sprimont; spoons unmarked.

Two pairs of salts by Nicholas Sprimont, 1742-3, Crab salts 8.9 x 17.8 x 11.7 cm; crayfish salts 8.7 x 14 x 14.1; spoons 11 cm long, The Royal CollecionLondon hallmarks for 1742-3 and maker's mark of Nicholas Sprimont; spoons unmarked.

The Royal Collection in U.K.

English Rococo Naturalism on Porcelain

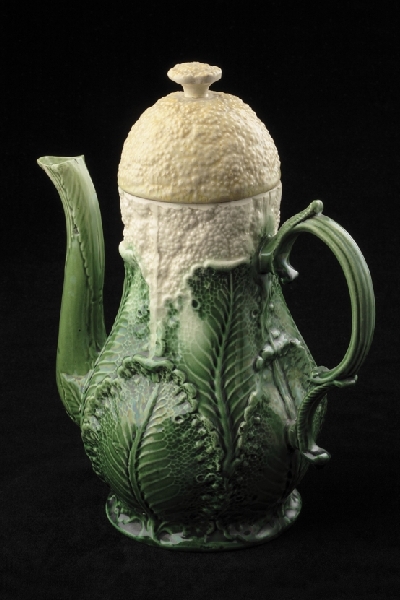

Tea Pot by Longton Hall, 1755The use of naturalistic forms, such as cabbages, melons and cauliflowers, was a direct result of the rococo style prevalent in Britain between 1740 and 1770. The style was particularly popular with both manufacturers and consumers alike. The rococo fruit shapes had already proved very popular when produced in porcelain by Chelsea, Longton Hall in Staffordshire and other factories.

Tea Pot by Longton Hall, 1755The use of naturalistic forms, such as cabbages, melons and cauliflowers, was a direct result of the rococo style prevalent in Britain between 1740 and 1770. The style was particularly popular with both manufacturers and consumers alike. The rococo fruit shapes had already proved very popular when produced in porcelain by Chelsea, Longton Hall in Staffordshire and other factories.

The block moulds for these forms were probably supplied by William Greatbatch. Several invoices survive from Greatbatch, in the archive collections, for "Colly Flower Ware" in September 1763.

Chelsea porcelain factory (1745-1784)

Salt imitating the original silver ware, by Chelsea, circa 1750The Chelsea porcelain manufactory (established around 1743-45) is the first important porcelain manufactory in England; its earliest soft-paste porcelain, aimed at the aristocratic market—cream jugs in the form of two seated goats—are dated 1745.

Salt imitating the original silver ware, by Chelsea, circa 1750The Chelsea porcelain manufactory (established around 1743-45) is the first important porcelain manufactory in England; its earliest soft-paste porcelain, aimed at the aristocratic market—cream jugs in the form of two seated goats—are dated 1745.

The entrepreneurial director was Nicholas Sprimont (1716-1771), a famous Huguenots silversmith, but few documents survive to aid a picture of the manufactory's history. Early tablewares, being produced in profusion by 1750, depend on Meissen porcelain models and on silver prototypes, such as salt cellars in the form of realistic shells. Chelsea was known for its figures. From about 1760 its inspiration was drawn more from Sèvres porcelain than Meissen.

In 1769 the manufactory was purchased by William Duesbury, owner of the Derby porcelain factory, and the wares are indistinguishable during the "Chelsea-Derby period" that lasted until 1784, when the Chelsea factory was demolished and its moulds, patterns and many of its workmen and artists transferred to Derby.

The factory history can be divided into four main periods, named for the identifying marks under the wares:

Triangle period (around 1743-1749)

These early products bore an incised triangle mark. Most of the wares were white and were strongly influenced by silver design. The most notable products of this era were white saltcellars in the shape of crayfish. Perhaps the most famous pieces are the Goat and Bee jugs in 1747 that were also based on a silver model. Copies of these were made at Coalport in the 19th century.

Raised anchor period (1749-1752)

In this period, the paste and glaze were modified to produce a clear, white, slightly opaque surface on which to paint. The influence of Meissen, Germany is evident in the classical figures among Italianate ruins and harbour scenes and adaptations from Francis Barlow's edition of Aesop's Fables. In 1751, copies were made of two Meissen services. Chelsea also made figures, birds and animals inspired by Meissen originals. Flowers and landscapes were copied from Vincennes.

Red anchor period (1752-1756)

Kakiemon (Japanese pottery), subjects were popular from the late 1740s until around 1758, inspired by the original Japanese and then by Meissen and Chantilly. Some English-inspired tableware decorated with botanically accurate plants, copied from the eighth edition of Philip Miller's The Gardener's Dictionary (1752) were also produced in this period.

Gold anchor period (1756-1769)

The influence of Sèvres was very strong and French taste was in the ascendancy. The gold anchor period saw rich coloured grounds, lavish gilding and the nervous energy of the Rococo style. In the 1750s and 1760s, Chelsea was also famous for its toys, which included bonbonnières, scent bottles, étuis, thimbles and small seals, many with inscriptions in French. In 1769 the failing factory was purchased by William Duesbury of Derby who ran it until 1784; during this time the Chelsea wares are indistinguishable from Duesbury's Derby wares and the period is usually termed "Chelsea-Derby".

wikipedia

Wedgwood

Coffee Pot by Wedgewood, 1759. Queen's ware and cream-coloured earthenware with deep-green glaze. Accession number : WMT-2007-04-1. 215mm height.Rococo-inspired wares formed a very small part of early Wedgwood production, but the most distinctive of these were those naturalistically-moulded earthenware fruit and vegetable forms made around 1760. Other potters in Staffordshire also made similar wares at this time.

Coffee Pot by Wedgewood, 1759. Queen's ware and cream-coloured earthenware with deep-green glaze. Accession number : WMT-2007-04-1. 215mm height.Rococo-inspired wares formed a very small part of early Wedgwood production, but the most distinctive of these were those naturalistically-moulded earthenware fruit and vegetable forms made around 1760. Other potters in Staffordshire also made similar wares at this time.

The lower portions of the cauliflower wares received a decoration of a brilliant green glaze, considered by many to have been developed by Wedgwood himself around the time of his partnership with Thomas Whieldon, master potter at Fenton.

The green glaze was Josiah Wedgwood's first significant ceramic development, created during his partnership with Thomas Whieldon, during March 1759. Wedgwood continued its manufacture once he was established in his first factory, the Ivy House Works in Burslem.

The green colour was derived from copper oxide, which was purchased from the specialist firm of Robinson and Rhodes in Leeds. Wedgwood's formula for "A Green Glaze to be laid on common white biscuit ware" is number 7 in his Experiment Book entered on 23rd March 1759. This book mention William Greatbatch ,with an associate of Whieldon and Wedgwood, is known to have supplied local potters with models and biscuit wares in these forms.

Coffee drinking was popular in Britain and coffee houses soon became a major feature of social life in the capital. Each coffee house attracted different professions. Josiah belonged to Old Slaughter's Coffee House.

Wedgwood Museum

William Greatbatch (1735-1813)

It is generally claimed that William Greatbatch was apprenticed to Thomas Whieldon

and first met Josiah Wedgwood I at Fenton. Greatbatch may have been acting for Wedgwood in London as early as June 1760. It is certainly the case that in 1762 he began a close business association with Josiah I, as well as setting up a pottery in his own right at Lower Lane, Fenton.

Greatbatch began to supply Wedgwood with a wide range of block moulds and biscuit earthenware (for colouring and glazing at Burslem) and probably finished wares also. An arrangement between the two potters seems to have been maintained until the mid-1770s.

Greatbatch continued in business for 20 years but was declared bankrupt in 1782. By 1786 he had gained employment at Etruria, on very favourable terms, and probably became general manager from 1788 until his retirement in about 1807. Josiah I evidently had high regard for his colleague and allocated him a substantial pension.

"WILLIAM GREATBATCH. A Staffordshire Potter", David Baker

The re-attribution of creamware, saltglaze, basalt, agate wares, printed wares,underglaze blue painted wares etc. once thought to be the products of Leeds, Whieldon and Wedgwood form but a part of this intriguing story. A crucial publication based on years of research following excavations on the Greatbatch site. David Barker, who directed these excavations, has written an authoritative and absorbing book. In 1979 the chance discovery of a potter's waste tip in Fenton , Stoke-on-Trent, led to a major excavation and the recovery of many tons of ceramic wasters discarded from a nearby factory. The tip and the pottery from it, have been positively attributed to William Greatbatch and span the whole twenty year period during which he was in business. Here for the first time, we are able to see the products of a single 18th century factory in their entirety and the excavated pottery now forms the most complete record of the products of any 18th century potter. The great range of material produced by Greatbatch is a surprise. Many pieces have previously been attributed to other factories and potters, such as Leeds, Whieldon or Wedgwood, but the evidence of archaeology is irrefutable. This publication has firmly established William Greatbatch as one of the most important names in English ceramic history.

Origin of Naturalism on Silverware

Dish in the Shape of a Leaf, Tang dynasty (618–906), late 7th–early 8th century

Dish in the Shape of a Leaf, Tang dynasty, China, late 7th century, L. 14.6cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art Close ties between China, regions in northwest India, and Iran in the fifth and sixth centuries led to the introduction of vessels made of gold and silver, some of which were included in burials as marks of the privileged status of the deceased.

Dish in the Shape of a Leaf, Tang dynasty, China, late 7th century, L. 14.6cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art Close ties between China, regions in northwest India, and Iran in the fifth and sixth centuries led to the introduction of vessels made of gold and silver, some of which were included in burials as marks of the privileged status of the deceased.

By the late seventh century, Chinese craftsmen had mastered the repertory of shapes, designs, and techniques prized in the West and adapted them to native conventions.

Shaped in the form of an artemisia leaf with a rolled tip, this rare dish is decorated with floral scrolls worked in repoussé. The scrolls end in leaves and blossoms or enclosed birds. Tang-period foliate dishes are found made of ceramics or bronze; however, this silver dish with parcel gilding is a unique example of the use of the form in precious metals.

Source: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Silver service, Song dynasty, 11th–13th century

Silver service, Song dynasty, 11th-13th century. H. 11.1cm, Diam. 19cmSilver with gilding, Diam. from 11.1cm to 19cm

Silver service, Song dynasty, 11th-13th century. H. 11.1cm, Diam. 19cmSilver with gilding, Diam. from 11.1cm to 19cm

Prior to the Tang dynasty (618–906), bronze, jade, and lacquer were the most highly prized materials, and silver and gold were used only sporadically, primarily for inlay.

Close ties among China, Persia, and the regions northwest of India developed during the fifth and sixth centuries and led to the introduction of vessels and utensils of gold and of silver that were frequently emulated in the seventh and eighth centuries.

Silver vessels produced during the Song period (960–1279) were used mainly for formal entertaining. This set of two plates, two small bowls, and a large bowl with a stand is likely to have been made in one of the cities along the lower reaches of the Yangzi River. These prosperous cities had become centers for the manufacture of luxury goods at the beginning of the dynasty.

The Museum's vessels share common shapes with Song pieces in porcelain and lacquer. The flower-and-bird decoration, in chased and punched work, was executed in a pure Chinese manner. Particularly noteworthy is the prominence of bamboo in the ornament, as this plant became a popular motif in the decorative arts only in the late eleventh century. The single trace of an earlier tradition, going back to the Tang dynasty, is the use of gilding over the areas of the designs.

Source: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bowl with petal design, 8th–6th century B.C. Anatolia, Phrygia, or Lydia

Bowl with petal design, 8th-6th century B.C., Anatolia, Phrygia, or Lydia. Silver, Diam 16.7cmSilver, Diam. 16.7cm

Bowl with petal design, 8th-6th century B.C., Anatolia, Phrygia, or Lydia. Silver, Diam 16.7cmSilver, Diam. 16.7cm

This hemispherical bowl has a raised boss in the center from which a petal design in repoussé radiates with chased details.

Parallels in shape and design with bronze bowls discovered in the so-called Midas Mound, close to the Phrygian capital of Gordion, suggest that this bowl was made in the eighth or seventh century B.C. by the Phrygians in Central Anatolia.

It is also possible, however, that the vessel was made later in Lydia in West Anatolia, where Phrygian artifacts were appreciated.

This type of design was imitated for porcelain and metal works in Tang Dynasty, 7th to 8th century.

Source: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Footed cup, first half of 14th century, Iran

Footed cup, first half of 14th century, Iran, Brass inlaid with silver. H 16.8cm, Diam 14cmBrass inlaid with silver, H. 16.8cm, Diam. 14cm

Footed cup, first half of 14th century, Iran, Brass inlaid with silver. H 16.8cm, Diam 14cmBrass inlaid with silver, H. 16.8cm, Diam. 14cm

Tall footed cups appear to have been popular during the Mongol period and are often illustrated in scrolls and miniature paintings.

The Chinese gold cup, which was excavated in Inner Mongolia, and the Iranian brass cup are comparable in proportions and decoration, with the lotus flower enclosed in medallions being a common motif. The nine-sided vessel has been associated with a type of lidded bowl called a ghulladan that was used as a money vessel for pious purposes in Islamic Ilkhanid Iran.

Source: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Top

Top Site Map

Site Map References

References About Me

About Me